Themes

Comparative Statistics and Gender Equality Legislation

Family Planning, Abortion and Contraceptives

LGBT Issues and Activism in Ukraine

Defining Ukrainian Feminism(s)

Women’s Activism at War and Revolution

Comparative Statistics and Gender Equality Legislation

World Economic Forum (2018). Insight report: The Global Gender Gap Report 2018

According to the Global Gender Gap Index, Ukraine is ranked 65 out of 149 countries, reaching a score of 0.708 which is well above the global average. Of 26 countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Ukraine is ranked as number 15. Ukraine may have narrowed its gender gap in estimated earned income and legislators, senior officials and managers, but other countries are improving at a higher pace. For instance, Macedonia FYR significantly improved in women’s representation in parliament and Montenegro significantly narrowed its gender gaps in terms of both health and economic participation and opportunity. The Gender Gap Index is composed of four sub-indexes. Ukraine was rated as number 26 out of 149 in educational attainment, 28 in economic participation and opportunity, 56 in health and survival and 105 in political empowerment. In all four sub-indexes, Ukraine had a better ranking in 2006. Most noteworthily, Ukraine went from being number 1/115 to number 56/149 in terms of health and survival. If interested in more statistics on the Ukrainian gender gap, go to pp. 281-288 in the report for tables with contextual Ukrainian data, nuancing the sub-indexes above.

Freedomhouse.org (2019). Ukraine. [online] Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/ukraine [Accessed 10 Sep. 2019]

Based on several indicators such as freedom of speech, freedom of movement, etc., Freedom House offers an overall evaluation of the degree of freedom in Ukraine as of 2019. The evaluation points to several discriminatory practices towards women and minority groups, leaving Ukraine with an aggregate freedom score of 60/100. Constitutionally, gender discrimination is explicitly banned, but in practice discrimination against the Roma minority and LGBT-people is extensive, for instance by employers and police. Furthermore, same-sex marriages are not recognized in Ukraine. Due to social discrimination, LGBT people’s ability to engage in political and electoral processes is limited. Officially, Ukraine has freedom of assembly if demonstrations are announced in advance. Yet the state mostly doesn’t provide sufficient security for demonstrators. Therefore, violence from non-state actors often prevent women’s movements and LGBT-groups from holding events. Allegedly, intrusive and aggressive counter protesters are not only allowed to be present during demonstrations, their agenda may be enhanced and helped along by police officers. Unsatisfactory police intervention is also seen in the limited response to reports of domestic violence. Furthermore, attacks on journalists, minority groups and LGBT-people are in many cases not followed by an adequate prosecution. Women and members of minority groups have the right to vote in Ukraine. Yet internal displacement and illiteracy lower the representation of these groups. By law, 30 percent of listed members in a party must be women. In practice, this is not the case. Ukrainian women, especially amongst internally displaced people, are vulnerable to exploitation for sex trafficking and forced labour in- and outside of Ukraine.

UNDP (2019). Comparative Gender Profile of Ukraine 2018-2019. [online] Available at: http://www.ua.undp.org/content/ukraine/en/home/gender-equality/comparative-gender-profile-of-ukraine-.html [Accessed 10 Sep. 2019]

This article from the United Nations Development Programme presents several statistics concerning gender inequality in Ukraine. As of 2017, Ukraine was rated as number 61 out of 160 countries in the Gender Inequality Index. The article stresses that women earn 21.2 percent less than men in monthly salaries. Based on data from 2017, 12.3 percent of seats in parliament were held by women. The percentage of female deputies in local municipalities is slightly higher. 46.9 percent of women and 63 percent of men form part of the labour force. Yet women spend about twice as many hours on household activities and childcare as men. Domestic violence is widespread, and in 90 percent of all cases the violence affects women. More than one fifth of women aged 15-49 have experienced at least one form of physical or sexual violence in their lifetime. For Ukrainians, the life expectancy at birth is significantly higher for women (77 years) than for men (67 years). Furthermore, men are more likely to commit suicide than women. Per 100,000 people, the suicide rate for men is 28.7, whereas it is 6.2 for women.

Equal Measures 2030 (2019). Harnessing the power of data for gender equality. Introducing the 2019 EM2030 SDG Gender Index

The SDG Gender Index seeks to show the gender aspect of each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. It thus measures gender inequality in relation to energy, pollution, poverty, etc. In 2019, Ukraine has a score of 71.0 on the SDG Gender Index and is ranked as number 46 out of 129 countries, just after Kazakhstan. The Ukrainian data shows that gender inequality is particularly prevalent in five of the goals: SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure), SDG11 (sustainable cities and communities), SDG13 (climate action), SDG16 (peace, justice and strong institutions), SDG17 (partnerships for the goals). Ukraine has a high degree of gender equality within SDG4 (quality education).

Melnyk Т. М. (2012). Creating the Society of Gender Equality: International Experience. Laws of Foreign Countries on Gender Equality

This report aims to find meaningful policy solutions that enhance gender parity in Ukraine by drawing on international legislative models. Melnyk argues that the full international body of knowledge on national, regional and global level is needed to reach the full potential of gender equality across countries. On pages 243-251, there is an English translation of the Act of Ukraine from 8th of September 2005 (№ 2866-IV) on the Provision of Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men. This serves as a starting point for becoming familiar with gender legislation in Ukraine.

Koriukalov, M. (2014). Gender Policy and Institutional Mechanisms of its Implementation in Ukraine: National review of Ukraine’s implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action and the outcomes of the twenty-third special session of the General Assembly

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, which was adopted by Ukraine in 1995, has empowerment of women as its agenda. This report assesses the current state of women’s empowerment in Ukraine and explores the possibilities of successful implementation of the Beijing Declaration within an array of themes, such as economy, education, health, gender-based violence, labour market, family issues, power and decision-making, media, environment and the girl child. The report thus gives a broad introduction to the state of gender affairs in Ukraine.

Femininity Ideals in Ukraine

Salem, H.: The Spectre of Berehynia, Opinion and Analysis

In this article, Harriet Salem describes how the figure of the Berehynia, a protector of the nation, has become a metaphor for matriarchal social structures in Soviet and post-Soviet Ukraine. The Berehynia is often used as a symbol of women’s central role in society, yet de facto, women have very little power in contemporary Ukraine. During the Orange Revolution, the female politician Yulia Tymoshenko repeatedly positioned herself as the caring nurturer of the Ukrainian nation. Yet Tymoshenko and her party blocked attempts at progressive legislation on gender. Feminist groups such as FEMEN have used the Berehynia-symbol of femininity to showcase its paradoxical nature. Feminist grassroot movements present in Ukraine have a hard time gaining general popularity, potentially because the Berehynia illustrates a deeply rooted identity crisis of women’s social role in Ukraine.

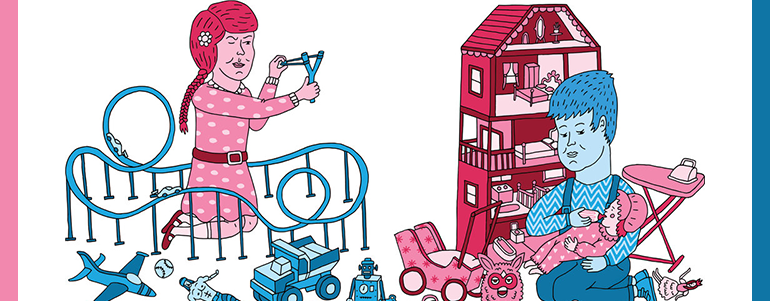

Kis, O. (2005). Choosing without Choice. Dominant Models of Femininity in Contemporary Ukraine. In: M. Hurd et al. (eds.) Gender Transitions in Russia and Eastern Europe. Stockholm: Gondolin Publishers, pp.105-136

In this chapter, Oksana Kis points to two dominant models of femininity in post-Soviet Ukraine. That of the Berehynia and that of Barbie. The two models both draw attention to female bodies. The Berehynia emphasizes the woman’s abilities of reproduction, nurturing and mothering, whereas the Barbie doll - the ultimate symbol of Americanization and globalization in Ukraine - draws attention to women’s bodies and women’s sex appeal, insinuating that women are made for men’s pleasure. Though these two ideas of femininity are dominant, many women in contemporary Ukraine promote and demand new sources of female identity, where women are seen neither as objects nor as designated servers of others’ needs.

Rubchak, M.J. (2009). Ukraine’s Ancient Matriarch as a Topos in Constructing a Feminine Identity. Feminist Review 92

In this article, Rubchak uses data from the media, advertisement, gender conferences, etc. to explore the conflicting discourses on female empowerment. By presenting initiatives aimed towards debunking gender stereotypes and promoting equal rights, she shows how old and new perceptions of gender constantly compete and intercept in the Ukrainian debate. Rubchak argues that though change is happening slowly, gender perceptions are in fact changing. Feminist discussions have, after all, been alive and well since Ukraine became independent.

Kis, O. (2012). (Re)constructing Ukrainian Women’s History: Actors, Authors and Narratives, In: O. Hankivsky and A. Salnykova (eds.), Gender, Politics and Society in Ukraine, University of Toronto Press

According to Oksana Kis, understanding present day’s gender order in Ukraine requires a profound understanding of Ukrainian history regarding gender. In this article, she discusses four dominant narratives of women’s roles in Ukrainian history: The Berehynia (women as protectors of the family and the nation), The Great Woman (women as contributors to the national cause), National Feminism (the national cause as superior to feminism and any other social movement) and Women’s Devotion (women suffering and sacrificing themselves for their nation). She notes that women are discursively presented as one unit, whereby they are denied diversity and individuality. Also, in continuously failing to represent women in historical accounts, women are instrumentalized and subordinate to the general, male-centred historical accounts. According to Oksana Kis, placing individual female accounts at the centre of historical research is a way of assigning agency to women, and such approaches are slowly becoming a trend in Ukraine.

Masculinity Ideals in Ukraine

Bureychak, T. (2012). Masculinity in Soviet and post-Soviet Ukraine: Models and their Implications. In: O. Hankivsky and A. Salnykova (eds.) Gender, Politics and Society in Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press

In this article, Tetyana Bureychak presents a historical account of Soviet and post-Soviet masculinity norms. In Soviet times, men were alienated from the private sphere and lost authority in the family, because women were assigned the role of caretaker in communist society, whereby the man’s role in the private sphere was purely economic. The Soviet man was expected to be a defender of the Motherland, a builder of communism, an athletic man and a selfless worker. Furthermore, he should worship powerful male leaders rather than aspire to become one. These expectations for the ideal man are conflicting, as some encourage benign behaviour while others encourage bravery and determination. Bureychak describes how Ukrainian masculinity has been presented as somewhat inferior to Soviet masculinity in Soviet media. The gender neo-traditionalism in post-Soviet Ukraine is partially a result of the fact that men are no longer the sole breadwinners of the family, nor do they have extensive responsibility for childcare and household. The lack of a clear purpose for men and the intense workload on women may explain the ‘patriarchal renaissance’ that post-Soviet Ukraine experienced after it gained independence. Just like Ukrainian femininity is shaped by the concept of the Berehynia, ideals of masculinity are shaped in the image of the Cossack, an equivalent to knights in medieval Western Europe. Cossacks are fertile, strong and courageous, and they do neither show emotion nor weakness. Ukrainian masculinity differs from Soviet masculinity in that it praises nationalism rather than communism and is understood is inherent rather than controlled by the state. It thus resembles Western understandings of masculinity in terms of financial success. Both in Soviet and post-Soviet times, men had more power than women, which is widely accepted in Ukrainian society. Statistics show that many people of both genders think that women are better caregivers than men, that men are better at business and decision-making than women, and that men should earn more than women. Besides the strong divide in men’s and women’s social functions, masculinity implies social practices that make up a serious health risk for men. This includes violence, unwillingness to visit doctors and high alcohol consumption. The norms of male aggression clearly affect women as well, for instance because domestic violence is very common. Yet initiatives against domestic violence normally don’t target male aggression.

Janey, B.A., Plitin, S., Muse-Burke, J.L. and Vovk, V.M. (2009). Masculinity in Post-Soviet Ukraine. Culture, Society and Masculinities, 1(2), pp.137–154

This study sets out to construct a thematic model of masculinity expectations from the perspective of Ukrainian men, using exploratory factor analysis procedures. The aim is to explore how Ukrainian masculinity can best be investigated. The model is constructed using the Multicultural Masculinity Ideology Scale that is globally prevalent, because it allows the researchers to include both universal and culturally specific elements of masculinity in the model. In order to test the model, the researchers gathered survey-responses from 191 male university students in Ukraine. By combining different variables about how men should act, the researchers create four components of Ukrainian masculinity based on Ukrainian history and existing research on gender. The components are: material wealth and sexuality (14.2 percent of the variance), emotionally reserved and confident attitude towards life (7.5 percent of the variance), competitive perseverance (6.2 percent of the variance) and reserved sexuality (5 percent of the variance). Overall, the results are deemed applicable to the construction of a Ukrainian Masculinity Ideology scale. The importance of prosperity and sexuality shows a certain link between Ukrainian and Russian understandings of masculinity, especially in terms of reserved sexuality and being a provider. Yet in the Ukrainian context, it seems that there is a culturally unique link between prosperity and one’s value as a husband. Existing literature supports a connection between Ukrainian men’s status at home and their economic success. In general, the researchers expect that since Ukraine is in the process of distancing themselves from their Soviet past and forming a new national identity, masculinity ideals unique to Ukrainian men will emerge. According to the survey, competitive perseverance and stoic protection seem to be ideals specific to men in Ukraine. Finally, the researchers note that the adoption of Western market economy may be the beginning of a notable shift in terms of Ukrainian masculinity ideals, because initiative and risk-taking were discouraged in Soviet society, and business was viewed as a female field.

Riabchuk, A. 2012, Homeless Men and the Crisis of Masculinity in Contemporary Ukraine. in O. Hankivsky and A. Salnykova (eds.), Gender, Politics and Society in Ukraine. Toronto University Press, Toronto, pp. 204-221

In this study, Anastasiya Riabchuk investigates the gendered dimensions of homelessness in Kyiv. In 2004, 80 percent of homeless people in Ukraine were male. On average, men are homeless for a longer period than women. Though women are very vulnerable when living on the streets, homeless men are subject to a higher degree of stigmatization than women. Being threatening, addicted to alcohol or mentally ill are some of the stereotypes that homeless men are met with. Riabchuk argues that in order to reach a higher level of equality, both structural and cultural factors of homelessness must be considered. In her interviews from 2004, the homeless men in Kyiv position themselves in relation to the stereotypes of homeless men, attempting to show why they have been ‘unjustly treated’, and why they are not ‘losers who have given up’, ‘alcoholics’ or ‘escapists’. Riabchuk thereby uses Tartakovskaya’s typology (2003) to analyse how homeless men represent extreme cases of ‘failed hegemonic masculinity’. Hegemonic masculinity implies being a strong, successful man who can provide for his family. Throughout the interviews, the Ukrainian homeless men demonstrate a strong sense of masculinity and they describe their actions of stealing or begging for money as attempts to provide for their families and preserve their masculinity.

Bureychak, T. and Petrenko, O. (2015). Heroic Masculinity in Post-Soviet Ukraine: Cossacks, UPA and “Svoboda”. East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies, Vol 2, No. 2

This article explores the reproduction of cultural ideals of masculinity, such as the strong, brave Cossack. In forming a nation built on strong masculinity ideals, men are marginalized and subordinated when they fail to live up to these standards. A party that gains legitimacy through the Cossack image and militaristic heroic masculinity is Svoboda. Svoboda is a right-wing party based on nativism and conservative values, securing family preservation through strong gender norms and homophobia. With a majority of members and supporters being men, most of their programs take the white able man as their point of reference. This means that military and defence policy is top-priority, whereas welfare policy is not considered as important. Solidifying a grand national narrative and protecting Ukraine from outer threats are Svoboda’s main projects. The intensified political ambient in Ukraine springing from Euromaidan is both a space of opportunity for social change and a space for men to practice ideals of heroic masculinity. There are many symbolic links between Cossacks and protesters in revolution-imagery. The protests are thus somewhat ambivalent, because they - despite their revolutionary and critical potential - are part of maintaining and strengthening gender norms in Ukrainian national identity and social practices.

Family Roles

Zhurzhenko, T. (2001). Free Market Ideology and New Women’s Identities in Post-socialist Ukraine. The European Journal of Women’s Studies Vol. 8 No. 1

When Ukraine gained independence in 1991, the ‘working mother’ gender contract was destroyed. Zhurzhenko argues that with the transition to a market economy, two forms of seemingly lucrative women’s identities were imported from Western culture: the businesswoman and the housewife. The free market ideology, she argues, is aligned with patriarchal perceptions of women as marginal due to ‘natural’ gender divisions of labour. In the Ukrainian context, economic survival forces women to combine being a housewife and a breadwinning businesswoman. According to Zhurzhenko, this silences critique of the existing political situation, because women are forced to direct all their resources towards their families - not towards political reform.

Koshulap, I. (2007). Cash and/or Care: Discourses and Practices of Fatherhood in Independent Ukraine. Thesis submitted to the Central European University in Hungary, Department of Gender Studies

Based on 20 interviews with married men and women with one child, Koshulap analyses the role of the father in modern Ukrainian nuclear families. The interviews explore how fathers navigate between the traditional role of detached breadwinner and the role of involved parent that is slowly becoming more prevalent in Ukraine. In the master thesis, Koshulap distinguishes between three archetypal roles: ‘father-nurturer’, ‘child’s-best-friend’ and ‘helping hand’. She came across one father-nurturer, almost taking on the archetypal role of the mother, and far the most men fell in the category of helping hands. The interviews reveal that men take some responsibility within the household, but strong emotional connection with the child remains a mostly motherly virtue. Unlike women, men are not expected to have the child as their first priority. None of the men mention providing for the family as being part of fatherhood. Initiatives such as paternity leave are quickly debunked, though, because the mother in most cases is unlikely to bring in a salary that is as high as the father’s salary. In addition to the above analysis, Koshulap presents and explains the relevant legal initiatives and state attitudes towards involved fatherhood.

Libanova, E.M. (2014). The Situation of Older Women in Ukraine. Analytical Report. Ukrainian Centre for Social Research and United National Population Fund

As the life-expectancy of women in Ukraine is much higher than that of men, almost two thirds of people in Ukraine aged 60 and above are women. Though women have a higher life-expectancy than men, the life-expectancy for women in Ukraine is noteworthily lower than in other European countries. Older people are vulnerable to poverty in general, yet women are more exposed due to the gender gap in pension income. The gender gap in pensions income is partially because of the lower pension age limit for women and because of the gender segregation in employment. As women often work low-paid jobs or part-time jobs, and in general are out of the workforce for longer than men due to longer education and maternity-leaves, they earn less pensions. This implies a serious disadvantage for older women’s health, because 40 percent report that they cannot afford medications and medical supplies, to not even mention surgery and hospitalization. In Ukraine, it is common for older women to help their younger relatives with childcare and financial assistance, especially when they live with their children and grandchildren. Older women are thus a key figure in primary care work and in allowing young women to form part of the labour market. The report offers extensive statistics and is rounded off with a list of policy suggestions for a Ukrainian active ageing policy.

Family Planning, Abortion and Contraceptives

Zhurzhenko, T. (2015). “Gender, Nation and Reproduction: Demographic Discourses and Politics in Ukraine after the Orange Revolution”. in Gender, Politics and Society in Ukraine

Though most literature on family in Ukraine highlights family as a private matter, for instance with regards to domestic violence, this article points to the many ways in which the state is interconnected with the family. The family and intimate life of individuals is often narrated in close connection to narratives of the nation. This is also the case in terms of family planning and childbirth, where Yuschenko openly encouraged families to have more children, for instance. Whether this pro-natalist agenda has grown after the Orange Revolution is contested. However, the one-time benefit upon the birth of the first child was raised from less than 800 UAH to 8,500 UAH in 2005. This sum was raised again to 12,240 UAH in 2008, while the mother gets 25,000 UAH upon the birth of the second child and 50,000 UAH upon the birth of the third (and every next) child. Pro-natalist politics is a contested measure of changing the critical demographic situation in Ukraine, where the population is constantly shrinking due to low birth rates, labour migration, etc. Though many politicians view this system of benefits as encouraging higher birth rates, experts have doubts about their long-term effect. They view the benefits as instruments of social protection for vulnerable social groups, because Ukrainian families with three or more children often live in poverty. All state initiatives regarding fertility affect women first and foremost. Mothers that are dependent on state support are often faced with double responsibilities, because state authorities hold them responsible for the social conduct of their children. Though pro-natalist concepts have not been translated into strict abortion-laws in Ukraine, the social consequences for women are seen in their economic status and their access to the labour market. There is a political fear that weaker gender norms and female emancipation would lead to a fertility drop. Yet Scandinavian politics suggest that birth rates can increase through shared parental leave and other policies that enhance female emancipation and labour market participation. Though some steps have been taken to bridge the gender gap in child care in Ukraine, the sufficient structural changes are not in place yet.

Perelli-Harris, B. (2008). Family Formation in Post-Soviet Ukraine: Changing Effects of Education in a Period of Rapid Social Change. Social Forces, 87(2), pp.767-794

In this study, Perelli-Harris investigates the correlation between child-bearing and education, exploring the causes of low birth rates in contemporary Ukraine. She writes that after Ukraine gained independence, maternity leave was expanded to three years, yet women (who had previously been employed) were paid 6 dollars per month and not 14 dollars as mandated by law. Furthermore, state-subsidized child care facilities declined by a third after 1990, both because of declining birth rates and because of privatization. Women therefore needed to take long maternity leaves or earn high salaries to afford day-care. Modern contraceptive methods have become more frequently used in the past decade. From 1994-1999, the amount of women ages 15-39 that used contraceptive methods increased by about 7 percent. The most recent data shows that 68 percent of married women and women living with a male partner use some form of contraception. In comparison with women with secondary or lower education, women with more than a secondary education are more likely to use contraceptives. By international standards, Ukrainian abortion rates are quite high. Marriage and childbearing have become less connected after the independence. Births outside of marriage increased from 11 percent in 1990 to 19 percent in 2002.

Wesolowski, K. (2015). Maybe Baby? Reproductive Behaviour, Fertility Intentions, and Family Policies in Post-communist Countries, with a Special Focus on Ukraine

In this thesis, Wesolowski comprises her research on gender and reproductive behaviour in Ukraine and Russia. She describes gender ideology and family policies in the Soviet Union and further compares post-Soviet Russia and Ukraine in terms of fertility rates, women’s living conditions and further developments in the countries’ family policies. She briefly summarizes the articles that the thesis is comprised of. The most relevant article for gender in the Ukrainian context, Prevalence and Correlates of the Use of Contraceptive Methods by Women in Ukraine in 1999 and 2007, is described in detail below.

Wesolowski, K. (2015). Prevalence and Correlates of the Use of Contraceptive Methods by Women in Ukraine in 1999 and 2007. Europe-Asia Studies, 67(10), pp.1523–1526.

In this article, Wesolowski presents her research on how Ukrainian state biopolitics influence contraception-usage in Ukraine (1999-2007). In Ukraine, several post-independence programs have focused on the reproductive health of the population, aiming to reduce abortion rates and to increase the use of modern contraceptive methods. The use of contraception decreased slightly between 1999 and 2007. This could partly be explained by the fact that a higher percentage of women were single in 2007 compared to 1999. However, modern contraceptive methods such as pills, condoms and IUDs have gained prevalence over traditional methods. Condoms are the most common contraceptive, because they are readily available and the cheapest solution. The study indicates that exposure to family-planning-messages correlates with the use of modern contraceptive methods. This may signify that state-induced family planning programs and biopolitics influence women’s contraceptive choice. However, the correlation could be due to other factors, which means that further research in the field is necessary.

Hilevych Y. (2014) Abortion and gender relationships in Ukraine, 1955–1970. The History of the Family. Routledge

In this article, Hilevych investigates the sociocultural conditions and culture regarding abortion in Soviet Ukraine 1955-1970, when modern contraceptives were not available, but abortion was legal. Based on in-depth biographical interviews and archival materials, she investigates how decisions regarding abortion were made in Lviv and Kharkiv. She finds that patriarchal gender regimes and spousal dynamics shaped when and how women took a stance regarding birth control and abortion in their relationship. In couples where spouses communicated about both birth control and abortion, the women sought less abortions and the men took more responsibility. This was more common in Lviv than Kharkiv. In Kharkiv, abortion was used to limit the size of the family, and spouses did not communicate about birth control and abortion. Birth control was considered a male domain and abortion a female. In these cases, women would seek abortions, both in their own interest and to maintain the patriarchal order in their marriage. In both Lviv and Kharkiv, couples conformed to the view of women being ignorant in sexual matters and men being responsible for birth control. Finally, Hilevych’ research suggests that women’s agency with regards to family planning can be highly reinforced through their peer networks.

Violence Against Women

UNIAN Information Agency (2018). Domestic violence now criminal offense in Ukraine [online] Available at: https://www.unian.info/society/2285764-domestic-violence-now-criminal-offense-in-ukraine.html [Accessed 25 Sep. 2019]

In December 2018, the Verkhovna Rada adopted bill 4952 on the criminalization of domestic violence, bill 5294 on preventing and combating domestic violence and bill 727 on applying additional measures against those who systematically fail to pay alimony. The bills took effect in 2019, and the influence of this criminalization of domestic violence is still to be seen.

UNFPA Ukraine (2018). 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence in Ukraine

Calling for action, this report shows through key-figures how gender-based violence is widespread and systematic in Ukraine. 83 percent of all violence in Ukraine is domestic violence, and 90 percent of gender-based violence is directed towards women. The National Representative Survey on the prevalence of violence against women and girls (2014) shows that more than 22 percent of 15-49-year-old women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence. Violence primarily happens during the night. This goes for all types of violence, be it physical, sexual or psychological. In general, there is little support for women who are victims of domestic violence. 12 Ukrainian regions have mobile teams giving psychosocial support and targeted assistance. Since November 2015, they have dealt with 40,388 cases of gender-based violence, and since January 2016, the National Gender-Based Violence Hotline received more than 82,477 calls. 82 percent of these cases were incidents of domestic violence. The report highlights that women who face several forms of discrimination because of their sexuality, ethnicity, physical abilities and health are much more vulnerable to all forms of gender-based violence and less likely to report incidents due to systemic discrimination and stigmatization. For example, more than a third of women diagnosed with HIV have experienced violence from a partner.

UNFPA (2018). Masculinity Today: Men's Attitudes to Gender Stereotypes and Violence Against Women

Based on survey results, this report explores the male perspectives on masculinity, family structures and domestic violence, ultimately aiming towards finding strategic methods for mitigating domestic violence. The survey shows that gender roles are closely related to responsibilities within the family, men being the breadwinners and women the caretakers. Yet the survey findings demonstrate a gradual transformation amongst young men, as many men ages 18-24 voiced that all family activities and tasks should be a joint responsibility or even equally divided. The survey also shows that young men are increasingly involved in family planning and the raising of their children. About one-third of men under the age of 40 reported to have taken a leave when their child was born. The same is true for 24 percent of men aged 40-49 and 18 percent of men aged 50-59. Even so, fathers spend less than half as much time with their children as mothers, and the fathers’ contact with their children is often limited to leisure activities and scolding.

The survey shows that domestic violence - emotional, economic, physical and sexual - is a widespread, normalized, systemic issue. A third of the respondents indicated that they have one or more male friends who commit physical violence against their partners, and a big proportion of the men report to having used violence themselves. Almost one-third of the men admit to having used emotional violence against their stable partners at least once in their lives, and one in seven respondents reported to have used economic violence in his partnership. 13 percent reported that they had used physical violence against their partners, and 5 percent of the surveyed men reported to have forced their unwilling partner to have sex or do sexual things. 3 percent report to have forced sex upon a woman who was not their stable partner. 18 percent of the men think that physical violence can be justified if a woman cheats on a man. 5 percent consider violence justifiable if a woman doesn’t want to have sex with her husband. A high percentage of the men also report that they exert social control over their partners. More than half of the men constantly want to know where their partner is, and 22 percent of the men regulate their partners’ use of clothes and make-up. 18 percent of the men tell their partners who they are allowed to spend time with. The survey results are based on self-reporting, whereby some underreporting of violence is expected. In 58 percent of cases, the violence is directed towards a wife or partner, and in many cases, alcohol or other substances are involved. The survey also shows a strong tendency for men to legitimize violence against women in general. For example, many of the men question the legitimacy of rape charges if the woman was affected by alcohol or drugs (about 50 percent), if the woman has a bad reputation (43 percent), and if the woman did not fight back (about 33 percent). More than 50 percent of the perpetrators who cooperated with social services to break the cycle of violence consider family conflicts a private problem. Yet about 25 percent admit that psychologists or social workers can help break patterns of violence if all family members are involved in the therapy. Of the perpetrators, 13 percent indicate that interventions towards the violent men may have an effect. Information campaigns, trainings and moral codex building were less supported. The men behind violent acts are less willing to listen to specialists than to their parents, friends and - to a lesser extent - their wives.

Dean, L. (2018). The Continuum of Gender Based Violence in Ukraine [Online] Available at:https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/wps/2018/10/23/the-continuum-of-gender-based-violence-in-ukraine/ [Accessed 11 Sep. 2019]

In this blog, Laura Dean comments on the state of gender-based violence in Ukraine before and after 2014 - the year the war in Eastern Ukraine broke out. She argues that though reporting of domestic violence has gone up in the years following the war, domestic violence was equally dominant before the war. According to a public opinion survey, nearly half of the Ukrainian population has experienced or witnessed domestic violence. As a result of the war, the focus on violence in society in general increased, which has spurred more awareness of domestic violence. Before the war, domestic violence was considered a private issue. However, with the increasing awareness of domestic violence, the government criminalized domestic violence in 2018 - with no state funding for its implementation, whatsoever. Housing privatisation poses an obstacle to women escaping violence as they become economically locked. Human trafficking was prevalent before the war and continues to be a big issue. Forced labour, sex trafficking and child begging flourishes in Ukraine due to gender inequality, labour migration, corruption and inefficient law enforcement and victim-stigmatisation, she argues. As a large group of Ukrainians have been internally displaced during the war, they are especially vulnerable in terms of trafficking. Labour trafficking of men has generally been dominant with the exception of 2015 where the majority of victims were female. Though the situation is grave, Laura Dean mentions the potential of new groups and institutions that may spur initiatives against gender violence.

UNFPA, Ukrainian Centre for Social Reforms (2017). Economic costs of violence against women in Ukraine 2017

In this report, UNFPA estimates the economic costs of violence against women. The estimates are based on 1) lost economic output due to death, reduced productivity and disability, 2) cost of medical and juridical assistance and 3) material losses and expenses of survivors. Based only on the registered violence cases, violence against women cost 10.8 million dollars in 2015. Adjusting for actual numbers of violent acts, the costs totalled up to 208 million dollars in 2015, equivalent to 0.23 percent of Ukraine’s GDP. The lost economic output in 2015 due to death and disability caused by gender-based violence is estimated at 3.7 million dollars for 2015. An estimate of 1.1 million women aged 15-49 years are subject to physical and sexual violence. The economic costs of the violence are primarily paid by the victims themselves, because the state does not provide shelters and specialized services for survivors. The cumulative expenses for the survivor amount to 190 million dollars annually. On average, Ukrainian women spend about 200 dollars on rehabilitation, etc., which is only possible with quite high salaries. Unemployed and low-income women are thus particularly vulnerable, no matter the extent of the violence they experience. International studies show that each dollar invested in preventing gender-based violence saves the economy 5-20 dollars in future service costs. The 25,600 dollars that were spent on preventing domestic violence in Ukraine in 2015 went to law enforcement and penitentiary systems, not to healthcare and social assistance for survivors.

UNFPA Ukraine (2018). Gender-based Violence in the Conflict-affected Regions of Ukraine. Analytical Report, Ukrainian Centre for Social Reforms

This report comprises the findings from a survey, interviews with women and female focus groups that address gender-based violence in the conflict-inflicted regions in eastern Ukraine, 2015. The survey covers the government-controlled areas, Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, and the oblasts with the highest influx of internally displaced people, Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhya and Kharkiv oblasts. Violence rates are significantly higher in these regions, and internally displaced people are more vulnerable when it comes to being exposed to violence. The report lists the frequency of different types of violence and discusses the circumstances of these incidents, such as where, when and with whom the violence occurs. Furthermore, it offers interesting statistics on why women do not seek legal, medical and psychological support. The most prevalent reason is that they do not experience a need for help. Other common reasons is the fear of future violence, no access to facilities near themselves and no trust in the personnel.

Martsenyuk, T. (2015). Early marriage in Roma communities in Ukraine: cultural and socioeconomic factors, Employment and Economy in Central and Eastern Europe, No. 1

In this study, Tamara Martsenyuk sheds light upon early marriage in Ukrainian society, particularly in Roma communities. The study investigates cultural and socio-economic factors that affect Roma women who marry early. In Ukraine, men and women can get married at the age of 18. However, the Family Code of Ukraine 16-year-olds can gain permission to marry if marriage is deemed in their interest. Pregnancy and religious beliefs are the main reason for permitting early marriage in Ukraine. The state program “Reproductive Health of the Nation 2015”, which holistically addresses different aspects of family planning, reproductive health and sexual education, is being implemented very slowly - especially in rural areas - due to insufficient funding. For women in the Roma minority, discrimination in health care is common, and Roma girls’ school attendance is below the national average. The notion that Roma’s make up a Ukrainian minority further silences Roma women’s public voice, because the discrimination they face is seen as cultural traditions rather than women's rights violations. Martsenyuk argues that there is a need for more gender-awareness in projects and research regarding Roma minorities, recognition of Roma women’s agency and critical approaches to how international organizations discuss early marriage.

DCAF and La Strada-Ukraine (2017). Criminal Justice Practice and Violence against Women. Assessment of the Readiness of the Ukrainian Criminal Justice System to Implement the Principles of the Istanbul Convention

Aiming to provide a baseline for improving criminal justice and policy responses to domestic violence and violence against women, this report assesses the current state of the Ukrainian criminal justice system. The assessment in made based on the requirements of the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (the Istanbul Convention), which was signed by Ukraine in 2011. The assessment reveals that three factors makes persecution of violence perpetrators ineffective in Ukraine. Firstly, most incidents of gender-based violence are not reported. Secondly, most reported cases of violence and rape do not result in convictions. Thirdly, there are neither initiatives to prevent violence from happening in the first place nor initiatives to prevent violence from repeating itself. The report identifies three main causes of the ineffective justice system. The first cause is pervasive gender stereotyping and gender bias, leading to victim blaming and silencing of culturally ‘private’ issues such as violence. The second cause is a lack of individual capacities in the criminal justice system. For instance, there is a lack of knowledge about domestic violence, and many practitioners are unaware of the dynamics of violence and the institutions available to support victims of gender-based violence. The third cause is insufficient institutional capacities. This is both due to understaffing and a lack of standardized trainings, guidelines and procedures for practitioners. Institutional as well as individual levels thus must be strengthened in order for The Istanbul Convention to be implemented.

Surrogacy and Sex Work

Swader, C.S. and Vorobeva, I.D. (2015). Receiving Gifts for Sex in Moscow, Kyiv, and Minsk: A Compensated Dating Survey. Sexuality & Culture

In this article, Swader and Vorobeva comparatively present the results of their study of compensated dating in post-Soviet countries. Compensated dating covers material compensations such as luxurious gifts, rent or travel in explicit exchange for sex. Sexuality in the public sphere, market economy and commercialization evolved simultaneously in post-Soviet countries, leading to sexuality being closely associated with luxury, wealth, and consumption. This article focuses on the outcome of the commodification of intimate relationships in Moscow, Kyiv, and Minsk. Compensated dating is just as prevalent in these cities as in the rest of the world. Yet the survey results indicate that the cities are different in terms of what characteristics make people take part in compensated dating. Receiving gifts for sex is linked to status in Kyiv and Moscow whereas it is linked to economic survival in Minsk. In Kyiv, women in the highest income group are 25 times more likely to have received gifts for sex that the poorest. In Minsk, women with lower education are much more likely to engage in compensated dating, and when the partner has greater financial means, the chance of compensation more than doubles. In Kyiv and Moscow, being compensated for dating and sexual favours it tied to an instrumental economic logic. However, the survey-results show that people who engage in compensated dating have the same values of family, love, leisure, marriage and sex as those who don’t - except for a moderate difference in the importance given to financial incentives and material well-being.

Kirshner, S. N. (2015). Selling a Miracle? Surrogacy Through International Borders: Exploration of Ukrainian Surrogacy. Journal of International Business and Law, Vol.14, No.1

In this article, Kirshner compares Ukrainian and American surrogacy with a special emphasis on the lack of international regulation. As a new and therefore scarcely regulated market, surrogacy leaves children, parents and surrogate mothers in vulnerable positions. The article focuses only on gestational surrogacy (where the surrogate is not the biological mother of the baby), which is the only legal form of surrogacy in Ukraine. Today, the international surrogacy market can easily be accessed online, and with very liberal approaches towards surrogacy, the market in Ukraine is flourishing. Surrogacy rates in Ukraine are estimated to increase by 40 percent in 2016, especially because many clinics are about to open, intended parents get to determine the gender of their baby, and the price for surrogacy in Ukraine is half that of the United States. In Ukraine, a foreigner seeking surrogacy is charged 30-45,000 dollars of which 10-15,000 dollars are for the surrogate mother. As more women sign up to be surrogates, the prices drop even more. In Ukraine, surrogates are not provided with any legal standing in case they want to claim any type of maternal affiliation with the implanted child and their rights and obligations are normally not clear in the contracts. Couples who partake in international surrogacy are seldom aware of the difficulties and bureaucratic procedures of bringing the child to their home countries, leaving some children in state care. Surrogacy can be considered a gift of life, but baby selling, exploitation of poor women by rich people, slavery and exploitation of cheap labour also form a significant part of the debate. It is therefore crucial to adopt better regulation ensuring proper procedures in international surrogacy.

Gender and Labour Market

United Nations Ukraine (2014). Analytical research on women’s participation in the labour force in Ukraine (2014) - United Nations in Ukraine. [online] Available at: http://un.org.ua/en/publications-and-reports/gender-and-gender-based-violence/4493-analytical-research-on-women-s-participation-in-the-labour-force-in-ukraine-2014 [Accessed 12 Sep. 2019]

This report offers a thorough analysis of women’s employment rate and employment conditions in Ukraine. In 2011, the employment rate of Ukrainian women was 57.5 percent, which was rather close to the EU-average on 58.5 percent and exceeded most South and Eastern European countries. However, the female employment rate in Ukraine is growing at a slower pace than in the EU, on average. During 2000-2011, women’s employment rates increased by 5-7 percent points in most EU-countries, while the rates in Ukraine grew by merely 2.4 percent points. It is emphasized that one of the reasons why Ukraine is slower than the rest of Europe is the difference in retirement age. In Ukraine before 2011, the retirement age was 55 for women and 60 for men, whereas the European retirement age is about 65, regardless of sex. The retirement age is now gradually increasing in Ukraine (60 years in 2021, regardless of sex). This could potentially increase female employment rates and strengthen women’s role in shaping the labour force. The pension status is the most dominant reason for labour market inactivity - a bit less than 50 percent for both genders. One would expect a considerable gender gap due to women’s lower retirement age, yet this is not the case. An explanation to this curiosity may be that early pensions due to illness and attrition are more prevalent among men. Besides retirement, men are often unemployed due to education. According to this study, the most dominant reason for women’s inactivity is a preference of home responsibilities. This applies to 45.7 percent of all unemployed women, and amongst unemployed women under the age of 40, family responsibilities are the main reason for unemployment in 79.9-85.5 percent of cases. Considering that a large share of housewives has a higher education, a large share of skilled workers are taken out of the labour force - be it voluntarily or involuntarily. Based on the economic crisis and other political developments in the 00’s in Ukraine, the report marks that male employment is more sensitive to economic cycle impacts and state labour market policy, for instance the 2005 presidential programme on creating 1 million new jobs annually. However, women were the first to be affected by the financial crisis, as the number of unemployed women started rising earlier and more intensely than that of men. In 2009, mainly male unemployment grew, but women were more vulnerable to dismissal at the time of economic downturn in 2008, and in the years after the crisis, female unemployment reduced at a slower pace than male unemployment. In Ukraine, the average wage for males exceeds that of women by more than one-fourth. According to the State Statistics Service of Ukraine, in all aggregate economic activities there is an economic gender gap reaching up to 30 percent. On average, the EU wage gap in 2011 was on 17.2 percent. The wage gap in Ukraine is partially due to the vertical employment segregation, where the more well-paid and powerful sectors are considered male territory, and the low-paid and assisting sectors are considered female. Women in management are few. Furthermore, the number of female managers is more prevalent in small-scale businesses. Besides the high level of cultural subconscious gender stereotyping, a lot of deliberate discrimination also takes place. Based on the generated knowledge, the report is rounded off with an array of policy recommendations that are worth a read.

Kostiuchenko, T., Martsenyuk T., Shurenkova, A. (2017). Gender-based Discrimination in Ukrainian Enterprises: Comparison of the Views of Experts, Top-managers and Personnel

Based on analysis of surveys and interviews, this article compares employers, employees and experts’ perceptions of gender-based discrimination in Ukrainian enterprises. Firstly, the study shows that gender stereotypes are prevalent and a source of discrimination in the workplace, both on the part of the employer and the employee. Women may be denied a job because of stereotypes regarding women’s skills and assumed wishes of motherhood. Yet women may also distance themselves from certain jobs because of disbelief in their own skills or for work-life-balance reasons. Secondly, the results show that there is a vertical gender segregation - which gives men better access to top management positions - and a horizontal gender segregation, which frames certain business areas as traditionally female or male. Women in top positions do mostly not have access to the networking fora that male leaders are naturally included in. Furthermore, women in leadership positions are expected to live up to male ideals, thereby often failing to improve conditions for other women in the industry. There are certain Ukrainian laws in place to ensure equal rights despite origin, social or financial status, race, nationality, gender, language, political views, religious beliefs, occupation and place of residence or other circumstances. Yet this is not common knowledge amongst Ukrainian employees and the violation of these rights do not face sanctions. Amongst top managers, only 59 percent (64 percent of women and 53 percent of men) reported having solid knowledge on the Ukrainian regulations regarding fair recruitment.

UNDP (2017). Women and Men in Leadership Positions in Ukraine: A Statistical Analysis of Business Registration Open Data

This report presents the trends of men’s and women’s leadership in officially registered institutions, organizations and enterprises. It investigates the effects of sectors, activities, regions and settlement types. According to the State Statistics Service data, 44 percent of women and 31 percent of men aged 15-70 are economically inactive. Overall, men hold significantly more leadership and management positions than women. Of all organization managers and entrepreneurs, 60 percent are men. In the field of individual entrepreneurship in Ukraine the gender gap is smaller, as 46 percent are women. The male dominance in management is particularly visible in sectors such as the construction sector, the energy sector, the transport sector, the agricultural sector, etc. In some sectors, women hold more management positions than men. Women occupy around 90 percent of management positions within beauty- and hairdressing, care work and primary education. Also, food- and textile-businesses are rather often lead by women. The percentage of female managers in legal entities in Kyiv is 4 percentage points lower than in other regions on average. Organization management in big cities is more gender-balanced, but mainly because men more often manage more “female” sectors in the big cities. The percentage of female independent entrepreneurs is greatest in cities that are bigger than villages, yet with a population under 100,000 people. As for the rest of management positions, the smaller the settlement, the more female managers.

Chepurko, G. (2010). Gender Equality in the Labour Market in Ukraine, International Labour Organisation

Besides giving a good overview of labour market politics regarding gender and social dialogue in Ukrainian enterprises, this report explores the potential for mitigating gender inequality through collective bargaining. Social dialogue and negotiations in Ukraine are conducted between trade unions, employers’ organizations and public authorities with the aim of reconciling workers’ interests with employers’ interest. These three actors are increasingly trying to promote equality for women and men in the workplace. However, trade unions, employer’s organizations and government officials lack awareness of gender issues and practical experience with implementing non-discriminatory policies and gender mainstreaming are insufficient. Chepurko argues that The Cabinet of Ministers must direct its activities towards improving gender legislation. In general, there is little monitoring of gender discrimination in the Ukrainian labour market. According to a survey, the investigation of discrimination complaints rarely takes place. Trade union staff is educated in practicing gender sensitivity in collective bargaining, yet more than 80 percent of the trade unionists involved in collective bargaining are men.

Libanova, E., Cymbal, A., Lisogor, L. and Larosh, L. (2016). Labour market transitions of young women and men in Ukraine. Results of the 2013 and 2015 school-to-work transition surveys. Work4Youth Publication No. 41. International Labour Organization

In this report, ILO gives an overview of Ukrainian economy and extensive quantitative data on the characteristics of Ukrainian youth and youth employment. As a recurring element in the statistical analysis, the report points to several gender differences in the transition from school to work in Ukraine (2013-2015). The survey findings show that the chances of completing a labour market transition is better for men (47.3 percent) than for women (35.1 percent). Yet finding employment after finishing an education takes 3.6 months for women and 6.6 months for men, on average. 49.8 percent of women have completed a higher education. As the same is true for only 38.3 percent of men, women are more highly educated than men in Ukraine. On the other hand, vocational education is completed by 29.8 percent of men and only 17.5 percent of women. The average wage of a young employee is 2,767 UAH, though young men earn significantly more than young women (men: 3,087 UAH, women: 2,343 UAH). Self-employed male workers earn on average 3,876 UAH, while self-employed women earn an average of 1,396 UAH. Young women are often employed in secure employment such as state-owned enterprises, whereas self-employment and private sector jobs are more prevalent amongst young men. The demographics of unemployed men are very different from those of unemployed women. Of unemployed women, 58.5 percent have tertiary education and 24.6 percent have vocational training. 34.9 percent of unemployed men have tertiary education and 47.3 person have vocational training. Furthermore, young women are more often employed as unpaid family workers. In 2015, the main reason given for leaving an education among young men was a lack of motivation to study (28.5 percent) and a wish to start working (22.8 percent). As for young women, 27.3 percent stopped their education for economic reasons. Also, 10.5 percent of women (and 5.5 percent of men) interrupted their studies to start a family. In 2013, an astonishing 31.3 percent of women stopped their education in pursuit of starting a family. Overall, a bigger proportion of women than men marry when they are very young. 29.2 percent of young women and 6.9 percent of young men ages 15-19 are married. In rural areas, early marriages are more common than in the cities for both men and women. The activity rates for women in Ukraine are traditionally lower than men. This is in part because women’s education is longer, but also because women are made responsible for the majority of household burdens in a labour market that doesn’t make employment and mothering easy to combine. The report states that men have easier access to transport cost allowance, more frequent overtime pay and a higher level of work security. Young women have easier access to child care facilities and services, and they benefit from paid sick leave, maternity leave and educational courses more often than men. Dependency on social state benefits is thus more common amongst women (7.1 percent).

ILO (2016). Employment needs assessment and employability of internally displaced persons in Ukraine: summary of survey findings and recommendations. [online]. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/budapest/what-we-do/publications/WCMS_457535/lang--en/index.htm [Accessed 12 Sep. 2019]

to this study conducted by ILO, the majority of unemployed internally displaced people are women (68 percent), less than 45 years old (74 percent), with a college (22.3 percent) or university diploma (46.3 percent). Most also have employment experience before their displacement (81.8 percent) and computer-skills. Statistics show that amongst internally displaced people, long-term unemployment of more than 6 months is higher amongst women, elderly and highly educated workers with working experience. Low-skilled male workers are thus better off when looking for employment. A higher share of women and older workers having flexible work schedules and temporary, limited-duration jobs. According to the report, almost 40 percent of women mark family and care responsibilities as reasons for their inactivity. Less than 4 percent of men mark this as reasons for their unemployment. Based on this, ILO recommends offering free or affordable child care in order to mobilize more women in job-seeking.

Hrytsenko, H. (2018). “Invisible battalion”: How Ukrainian women secured the right to fight on a par with men [online] Available at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/invisible-battalion-ukraine/ [Accessed 12 Sep. 2019]

Women in civil society have played a big role in the armed resistance since the beginning of the war in 2014. About 8 percent of the Ukrainian Armed Forces are now women. Yet only a tenth of these women have risen to officer rank and none of them have become generals. Though there are many women in the army, the state has been slow to ensure their rights, legally and practically. In order to draw attention to the importance of women in warfare, The Invisible Battalion project was founded by female soldiers with support from the Ukrainian Women’s Fund and UN Women. The project aims at improving gender equality in the army through lobbying with authorities and working with the public. Up until 2017, the legal framework established by Ukraine’s Ministry of Defence was very outdated and based on Soviet perceptions of protecting women. Women were not allowed in military professions except assisting roles such as nurse, chef or field banya directors. Women serving in the army were thus registered as accountants or not officially registered at all, giving them less benefits, lower salaries and less recognition. Women were infrastructurally invisible, as they were not provided with uniforms, footwear, feminine sanitary protection or access to gynaecological services. Furthermore, women in the military have dealt and still deal with great stigma from male colleagues and society as such. For instance, they are often accused of neglectful behaviour towards their families. Though bill no. 6109 that prohibited women from 450 professions was revoked in 2017, women are still not given access to secondary and higher military education, and a female-friendly infrastructure at the front is also not well established, calling for more legislative and practical action towards gender equality.

Heinrich Böll Stiftung Kyiv. (2019). Women and Men in the Ukrainian Energy Sector: Equal Rights and Opportunities or a Sector of Discrimination? [online] Available at: https://ua.boell.org/en/2019/07/22/women-and-men-ukrainian-energy-sector-equal-rights-and-opportunities-or-sector [Accessed 11 Sep. 2019]

This article comprehensively presents the results of a study conducted in 2018/2019 in the Ukrainian Energy Sector. The study was conducted by the Institute for Economics and Forecasting of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation Kyiv, Women’s Energy Club of Ukraine and the Government Commissioner for Gender Policy. The study shows that there is a severe gender gap in the energy sector. Internationally, women possess only one fifth of jobs in the energy sector, and in 99 percent of cases, senior management positions are held by men. In Ukraine, the immense gap exists due to many factors. According to the survey, women are three times less likely to want a degree in engineering than men. Women in the energy sector also face discrimination to a higher extent. In the energy sector, 2 percent of men have been discriminated against based on their gender. This goes for 19 percent of women. One third of the survey participants expressed that they cannot get uniforms that fit, and 10 percent complain about the lack of separate dressing rooms for men and women. Besides the gap in education and general access to this field, family structures are part of the challenge. Maternity leave and sick leave are a responsibility that rests primarily on women, whereas men work overtime more often. The biggest wage gaps in the Ukrainian energy sector are observed in the mining industry, where women by law are forbidden to have certain functions in the workplace. In the field of renewable energy, a lower level of gender inequality has been observed.

British Council (2018). Gender Equality and Empowerment in the Creative and Cultural Industries: Report for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Ukraine

In this report on the so called ‘Eastern partnership region’, the British Council maps out the gender gap in the creative and cultural industries. The report is based on a study including quantitative data, fieldwork and several interviews. The report contains worth-to-read quotes from the interviews and interesting methodological considerations on investigating the politicized theme of gender in post-Soviet countries. In the Ukrainian cultural and creative industries, architecture, IT, television, commercial filmmaking and performing arts are mostly male-dominated. Museums, galleries, libraries, documentary photography and publishing are female-dominated. Design, advertisement and marketing are amongst the more gender-balanced areas. Technical and better-paid sectors are predominantly occupied by men, including leadership positions, and the field study shows a significant wage gap between men and women in the creative industries. When women enter the creative and cultural field, the study shows that women tend to undervalue their worth which makes them prone to accepting low salaries. Furthermore, they seek flexible work in order to simultaneously manage childcare and household chores. Men, on the other hand, often compromise their wish for a creative work life in order to earn more money and provide for their families.

Dutchak, O. (2018). Devaluation of Female Labor and the Retreat of the State. Austerity, Gender Inequality and Feminism after the Crisis in Ukraine. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung

As a response to the economic decline in the years after Maidan, the government introduced more neoliberal policies by cancelling fuel subsidies, cutting social costs and increasing the retirement age. The socioeconomic costs for women of these initiatives have not been assessed, and Dutchak argues that existing mainstream discourses on gender inequality generally fails to address structural problems. This means that fundamental structural changes are not the most visible aim of feminist initiatives. Dutchak addresses the discrepancy between façade equality and the real situation of women and women’s wellbeing in Ukraine after Maidan and reviews existing legislation and implementation of gender inequality initiatives. She further documents how the reproductive labour of women is continuously devaluated and made more difficult, while their access to productive labour is also further complicated by austerity. Finally, she discusses mainstream and leftist Ukrainian feminism and the possibilities for provoking structural change through leftist feminism.

Women in Ukrainian Politics

Zakharova, O., Oktysyuk, A. and Radchenko, S. (2017) : Participation of Women in Ukrainian Politics. International Centre for Policy Studies (ICPS)

This report gives a thorough overview of women in Ukrainian politics from its foundation in 1991 up until today. Though there were more women in the Ukrainian Parliament, Verkhovna Rada, in 2014 (12 percent) than in 1991-1994 (3 percent), the gender gap in Ukrainian national, regional and local decision-making units continues to be massive. No woman has been Chairperson of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. In the VIII Convocation 2014, Oksana Syroid was the first woman ever in Ukrainian politics to gain a leadership position as Deputy Chairperson, and in 2016 Iryna Gerashchenko was elected as First Deputy Chairperson of the Verkhovna Rada. In recent years, certain committees against gender inequality have been formed, and they are all headed by women. Furthermore, women have gone from only being represented in committees regarding education and social policies to being represented in all committees. However, no women have been part of the budget forming committee. According to the data of the National Democratic Institute 2013, women made up 12 percent in the regional councils, 23 percent in district councils, 51 percent in rural councils and 46 percent in settlement councils. Women are thus almost not present in the more influential and prestigious positions. In Kyiv, Sevastopol and cities that are regional centres, only two women have been elected as mayor (Zhytomyr, 1996 and Kherson, 1994). As of 2015, the 30 percent electoral quota took effect. It provides that there should be no less than 30 percent of the same sex on the parties’ electoral lists. This rule was not adopted easily, and it was off to a slow start as very few parties followed this quota. The report contains data on each of Ukraine’s political parties’ performance in this regard.

Ukrainian Women’s Fund (2010). Increasing Women’s Representation in Decision Making through Political Parties

This report is based on the results of a survey carried out among the political parties represented in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Out of 16 political parties represented in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, eight agreed to participate in the study: All-Ukrainian Union ‘Fatherland’, European Party of Ukraine, People's Party, People's Movement of Ukraine, Political Party ‘Forward, Ukraine!’, Ukrainian People's Party, Ukrainian Republican Party ‘Sobor’, and Ukrainian Social Democratic Party. All eight political parties claim to have no discriminatory policies towards female party members, and they express that men and women make equally good politicians. What matters is experience, principles and political will. In most parties, women are represented practically equally among members. However, the leading political positions are almost exclusively held by men. The leadership positions are supposedly granted based on skills and meritocracy, and most of the parties were disinterested in strengthening the role of women in their parties. None of the participants support the idea of establishing quotas for women and do not believe it would increase the number of women in politics. As the only two, representatives of ‘Batkivshchyna’ and the People's Party actively identify leadership potential amongst female members and support the idea of implementing training programs for women. The parties point to the following as challenges of female political participation: traditional family structures, poor organization of the Ukrainian women’s movement, disinterest in leadership roles on the part of women and opposition of male politicians.

Rubchak, M.J. (2012). Seeing pink: Searching for gender justice through opposition in Ukraine, European Journal of Women’s Studies

In this article, Rubchak identifies and explains two waves of opposition in Ukrainian society after the transition from totalitarianism towards democracy. The First Wave is a neo-traditional rejection of communist values. The Second Wave is a rejection of the newly established cultural codes. Within both waves there are elements of female emancipation. Neither of the two have manifested themselves as organised national movements. The first wave was dominant up until 2008 and was primarily centred around creating a national identity with women as centipede. In this context, the Berehynia figure has been important as it symbolizes the reproductive, nurturing and nation-protecting character of womankind. The first wave would thus liberate women from Soviet all-encompassing masculinity and allow their female nature to flourish. Some first-wave-protesters would demand equal rights, given the seemingly central role of women in society. The second wave was run by primarily young students, openly criticizing the lack of gender justice in the system. This is exemplified through the movement FEMEN, which raises awareness of trafficking and prostitution through provocative political protests. FEMEN’s activities are thoroughly described in the article.

Kis, O. (2007). "Beauty Will Save The World": Feminine Strategies in Ukrainian Politics and the Case of Yulia Tymoshenko

In this article, Oksana Kis deconstruct central-right politician Yulia Tymoshenko’s political image in order to reveal the secrets of her success. Rubchak argues that women in politics must live up to Ukrainian ideals of femininity to gain votes and popularity; they must radiate that they are virtuous mothers of the nation (Berehynia) and national sex symbols (Barbie). The article shows how Tymoshenko rhetorically applies these symbols of womanhood and victimized martyr when staging her political worth. Tymoshenko is known for being a tough political figure, which is often mentioned as a contrast to her beautiful exterior or portrayed through symbols of militant femininity, such as an amazon. Though Tymoshenko would never claim to be a feminist, her actions and multifaceted interpretations of her own femininity says otherwise. Furthermore, Tymoshenko rarely comments on women’s roles, but she has nevertheless voiced that women should be more influential in political decision making.

Martsenyuk, T. (2012). Chapter 1: Women’s Top-Level Political Participation. Failures and Hopes of Ukrainian Gender Politics. In: O. Hankivsky and A. Salnykova (eds.) Gender, Politics and Society in Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press

In this chapter, Tamara Martsenyuk discusses the possibilities, strengths and weaknesses of introducing gender quotas in the Ukrainian political system. The chapter includes interesting statistics based on the public opinion survey ‘Opinions and Attitudes of the Ukrainian Population’ from 1999, 2007, 2008, 2010. Besides showing trends and development over time, the data shows how a large percentage of both men and women agree that women should put their husband’s career above their own and that men are more suited for politics than women. Martsenyuk argues that men have to become more involved in household and care work to give women the time that is required to advance to top-level positions within politics.

Dean, L.A. and Dos Santos, P. (2017). The Implications of Gender Quotas in Ukraine: A Case Study of Legislated Candidate Quotas in Eastern Europe’s Most Precarious Democracy, Teorija in Praksa, Vol. 54, No. 2

Despite introducing a 30 percent gender quota for parties in the municipal elections in Ukraine in 2015, there was not a major increase of women in local legislative offices. According to Dean and Dos Santos, this was due to a lack of enforcement of the gender quota law. In this report, they compare the candidacies and election of women to local councils in 2010 and 2015, showing the representation of women within each party and each region. Furthermore, they explain how the quota law came about and its lack of enforcement.

LGBT Issues and Activism in Ukraine

Nash Mir (2011). One Step Forward, Two Steps Back. Situation of LGBT in Ukraine in 2010-2011

Getting off to a good start, Ukraine was the first post-Soviet country to decriminalize homosexual relations. However, Ukraine is no longer so progressive when it comes to LGBT-rights. In Kyiv, about two thirds of the general population consider homosexuality a perversion. About 60 percent of LGBT-people often face physical violence, sexual assaults, hate motivated crimes and discrimination within the past three years. For LGBT-people whose sexuality is publicly known, 89 percent had experienced discrimination. The most common spheres of discrimination are in the workplace and from police officials. Most homosexual people in Ukraine do not trust state authorities and the government. 41 percent of the survey respondents have experienced violence or harassment from people in their close surroundings. In 18 percent of the cases, the harassment was on the part of family members either limiting the respondent's freedom of movement or kicking them out of home. The most common harassments are insults (58 percent), disregard and debasement (32 percent) and threat of physical violence (24 percent). In 13 percent of the cases, respondents were physically attacked. The report further offers statistics and excerpts from interviews with transgendered people about their experiences of discrimination in the labour market.

Nash Mir. (2009). An Investigation into the Status of Same-Sex Partnerships in Ukraine [Online] Available at: http://gay.org.ua/publications/same_sex_partnership-e.pdf [Accessed 19 Sep. 2019]

This report from 2009 focuses on the everyday life of same-sex couples in Ukraine, investigating social identities of same-sex partners as well as needs and values of the couple. The researchers ran a survey on homosexual and bisexual people, asking them about their same-sex relationships. 47 percent of the survey respondents co-live with their same-sex partner. In 2000, only one third co-lived. The study shows that female couples are more likely to co-live, whereas male couples often live separately. Furthermore, couples in villages and smaller cities are less likely to live together than couples in the bigger cities. One tenth of the same-sex couples in the survey are raising a child together. More than half of the respondents who have no children would like to have children. Of bisexuals in the sample, 13 percent did not wish to have children. The same goes for about one third of homosexuals. About 75 percent of the respondents consider monogamous relationships the ideal model for same-sex couples. Same-sex couples are challenged by condemnation from family and society at wide, and for instance adopting the child of a partner is challenging for about half of the respondents. According to this survey, men are more likely to face condemnation from relatives (61 percent) than women (39 percent). Also, 86 percent of men report problems with receiving pensions of a deceased partner. This is reported by 14 percent of women. The same goes for regulating property rights, which is a challenge for 65 percent of men and 35 percent of women. Though this study gives some insight in the demography of same-sex families, it is investigated from a quite normative stance, suggesting that marriage, monogamy and children leads to higher life satisfaction. The data collection and data presentation in this study is somewhat value laden - heteronormative and assuming - and sometimes imprecise in commenting on survey findings. With that being said, the report does provide some knowledge within an else way quite unstudied field.