Workplace diversity policies are not a whim but a way to help employees realize their professional potential to the best of their ability. This principle is especially true for the Armed Forces of Ukraine, which is engaged in active combat operations and does not have the luxury of “throwing away” human resources because of individual characteristics that are not directly related to performing duties.

According to research, at least 3% of people in the United States identify as LGBT+, and 8-11% report homosexual behavior or awareness of homosexual attraction.[1] There is no such research available for Ukraine. Still, one can assume that the percentage of people with non-heterosexual orientation is not country-specific, so the proportion in Ukraine should be around the same.

In Ukraine, homosexuality or bisexuality is not a condition for removal from service, and same-sex romantic or sexual relationships are not prosecuted and do not breach military law. Therefore, it can be assumed that homosexual and bisexual persons enlist in the Ukrainian army evenly in accordance with their percentage of the population. This means that at least 3% of the personnel of the Armed Forces of Ukraine (more than 9,000 people as of the beginning of 2022, before mass mobilization to counter the Russia’s full-scale invasion, and much more after it began) are homosexual or bisexual. Thus, they all are the target audience of potential anti-discrimination policies.

The rights of LGBT+ military personnel in the EU and the U.S

Since 2018, LGBT+ people have been free to serve in the military in all EU countries. NATO policy prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation, and since 2002, it has extended benefits for military families to same-sex military families. Since 2019, NATO has had a Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan until 2023, focusing primarily on gender equality and nationality equality within the organization. The organization introduced the official International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia (May 17) in 2020.

In 2021, NATO headquarters hosted the first internal conference on LGBTQ+ perspectives in the workplace.[2] Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg delivered a speech in which he noted that “every member of the LGBTQ+ community at NATO is a valued member of our staff and family.”[3]

This inclusion was preceded by a struggle, first of all, for the recognition of the LGBT+ community as such. In this text, I will briefly focus on examples from the United States and Germany.

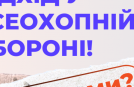

American society was quite conservative after World War II, and media products that openly targeted homosexual men could not be disseminated. Therefore, health and fitness magazines targeted the audience by publishing visual materials depicting male bodies. In 1956, the Finnish artist Touko Valio Laaksonen submitted his drawings to Physique Pictorial magazine and signed them “Tom.” In 1957, they were first published under the pseudonym “Tom of Finland”, invented by the editor. Since then, Tom’s work has become iconic and greatly influenced queer culture in general and erotic art. Tom painted erotica with men of his liking: tall, strong, engaged in physical labor, in a police uniform, or the outfit of a sailor or a soldier. His works influenced the self-awareness and imagery of the homosexual community, previously dominated by male femininity. They also probably indirectly contributed to the inclusion of the LGBT+ community in power structures.

Tom of Finland. Untitled. 1974

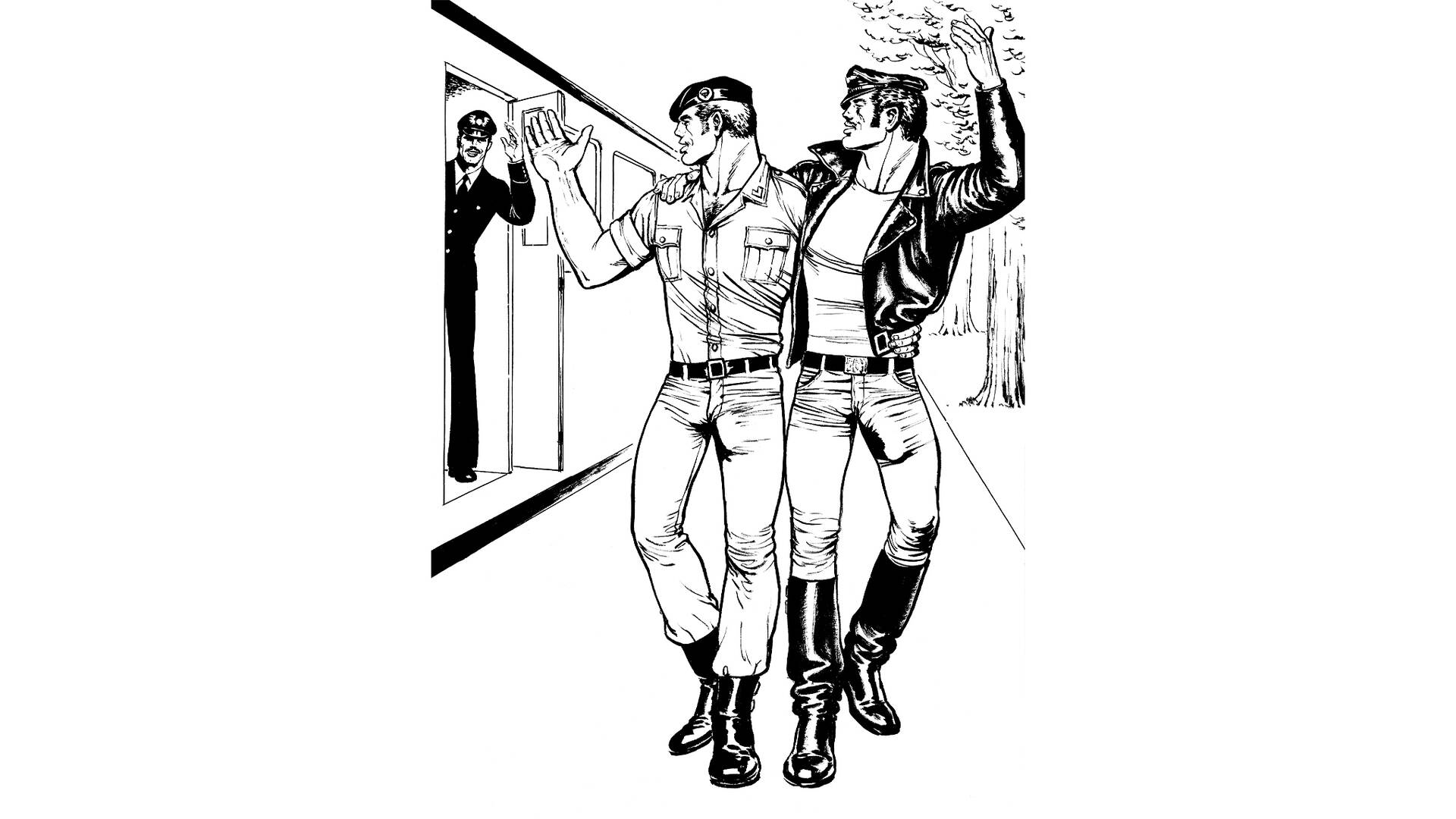

Simultaneously, as part of the human rights “track”, Vietnam War veteran Leonard Matlovich became the second openly gay person to come out after Harvey Milk. Being white, Matlovich started with anti-racist activism and later realized the similarities between racial and sexual orientation discrimination. He came out in 1975, first to his superiors and then to the media, making the front page of The New York Times and the cover of Time.

At the same time, he had to defend in court his right to remain in the army. Initially, he was offered to stay on the condition that he would never practice homosexuality again, which Matlovich did not agree to. The trial lasted until 1980, and Matlovich eventually won – he was reinstated and even promoted. In return, the army offered him to resign with financial compensation. Given the risks of being discharged again for another arbitrary reason and a possible appeal to the conservative Supreme Court, Matlovich chose to accept the money. During his military retirement, he went into business and continued to engage in activism, including fighting for the rights of HIV-positive people, which he was himself since 1986.

In 1993, the anti-homosexual personnel policy was somewhat eased by introducing the compromise principle of “Don’t ask, don’t tell.” It was assumed that closeted homosexual and bisexual men could serve if they remained closeted, and their superiors could not question or provoke them to come out. This policy was repealed only in 2011, and only then did homosexual and bisexual people gain the opportunity to be open during their military service.

The cover of Time magazine with Leonard Matlovich. 1975

In Germany, the LGBT community’s struggle for recognition, particularly in the military, also has a long history, burdened by 12 years of Nazi dictatorship. The biopolitics of the Third Reich were not limited to anti-Semitism and racism; they included strict health and family reproductive behavior requirements. In general, even before the 1930s, “immorality” and conspiracy were often equated in society, and gays were described in the same negative terms as Jews. Section 175 of the 1871 Criminal Code, which explicitly criminalized sexual acts between two men, was amended in 1935 to cover all homosexual behavior, including dating and flirting. Often, SS officers disguised themselves as gay to catch real ones. Between 1933 and 1945, more than 100,000 people were arrested under the new edict of Section 175. After the fall of the Third Reich and the release of people from concentration camps, the conservative Adenauer government came to power, which did not seek fundamental changes, so people from this group were repeatedly sentenced to prison. In the GDR, homosexuality was decriminalized in 1968; Germany abandoned the Nazi version of Section 175 in 1969, but it was wholly repealed only in 1994. A long struggle for the recognition of rights preceded the repeal.

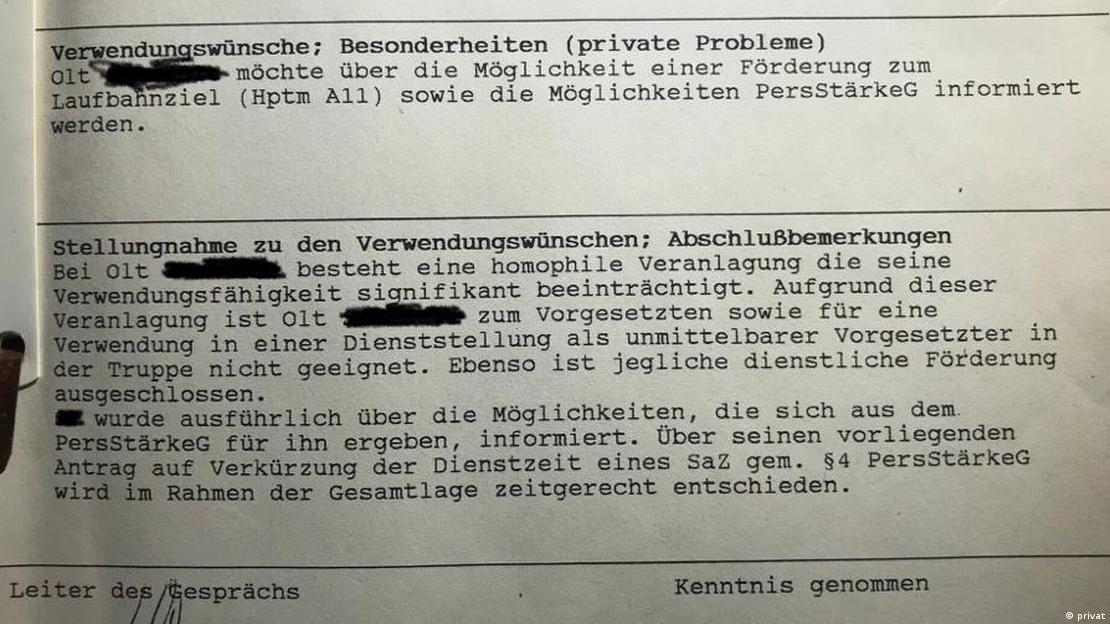

Society’s conservatism influenced the official policy of the Bundeswehr. It was believed gays in leadership negatively affected morality and posed a security threat. In 1984, General Gunther Kissling was forced to resign because of suspicions of homosexuality. Discrimination at lower levels was much more widespread and less publicized.

Extract from a forced medical examination, which indicates a ‘ban on promotion’. 1987

Nevertheless, the community’s struggle for its rights continued, including in court. In the late 1990s, at least two German soldiers, Winfried Stecher and Werner Buzan, tried to defend in court their right to serve.[4]

It was only in 2000 that the Bundeswehr allowed women to serve (earlier, they could only serve in medical corps) and openly gay people to hold leadership positions. In 2002, the unofficial group Queer BW was founded to demand an official apology and rehabilitation for those affected by this discriminatory policy. They had to wait 18 years for an apology, until 2020.[5] At present, service members who experienced harassment during their military service can seek compensation for the harm they endured.

The logo of the Queer BW initiative

LGBT+ military personnel in the world’s armies

Latin American countries have not yet reached the top of inclusivity indexes, but they have been making rapid progress in recent years in the rights of the LGBT+ community. Pride in São Paulo, Brazil, is considered the largest in the world, and the marriage rights of same-sex couples in the military are ensured.[6] However, Brazilian military law prohibits sex in the service, as such. In Mexico, homosexuality has been decriminalized since the second half of the 19th century, and homosexuals have been allowed to serve in the army since 2012. However, domestic homophobia in these countries is still a significant problem. On the other hand, Argentina is a champion of LGBT+ rights in the region, which lifted the ban on homosexuals serving in the military in 2009.

China’s policy of inclusiveness concerning LGBT+ in the military is unclear, and information on this topic is partially limited.[7] However, it is known that the Chinese army’s personnel policy seeks to attract as many citizens as possible to serve, and it is likely that closeted homosexuals are fully employed, while open homosexuals risk dismissal.

Conservative and homophobic countries in Asia and Africa cannot tout inclusion in the military: in Uganda, homosexuals are potentially subject to the death penalty; in Iran, homosexual behavior often entails forced transition to the female gender.

LGBT+ military in the USSR and in Ukraine

After the fall of the tsarist regime, the new Soviet government discarded all imperial criminal law, particularly prosecuting homosexual behavior, following the German model. At the same time, the attitude towards LGBT+ people in the Russian Empire was conditionally tolerant for those times, without high-profile criminal trials (recall the Oscar Wilde trial in the UK). For public and/or influential people, public intolerance was limited at best to rumors and at worst to administrative measures (dismissal from office, expulsion from the capital). Criminal trials concerned only ordinary people and were initiated mainly based on third-party complaints.

The new Bolshevik government moved beyond this moderate intolerance: through the direct abolition of imperial legislation, the decline of the church’s influence, and a general attitude of emancipation and liberalization in gender and sexual issues. The proclaimed gender equality and affirmative action of “women’s departments,” the legalization of abortion, the “glass of water theory” that separated sex from love, and the development of a system of “children’s hearths” (extended-stay kindergartens) were naturally accompanied by a more tolerant attitude toward homosexuality.

Over time, the emancipatory program of the first years of Soviet rule began to wind down gradually, and in 1933, the USSR criminalized homosexuality again. The article of the criminal codes of the Soviet republics entitled “Sodomy” provided for punishment for sexual relations between men. At the same time, the prison world developed practices of establishing hierarchy through sexual domination and ritual impurity attributed to victims of such domination and to the objects of prison life they touched. These firmly entrenched negative associations with homosexuality. Following a series of camp uprisings in the early 1950s and the relative liberalization of Soviet policy after Stalin’s death in the second half of the 1950s, the Gulag system was gradually dismantled, with large numbers of prisoners released and reintegrated into society. The homophobia they brought with them from the prison environment quickly spread further.

The Soviet army did not explicitly ban homosexual men from service. However, those convicted under the relevant criminal article were not drafted into the military, and confessions of homosexuality to a medical commission could in practice be qualified as a psychiatric disorder and exempted from service. Nevertheless, closeted homosexuals apparently joined the army on a general basis. Little research has been done specifically on this topic because of its great taboo, but it is logical to assume that in combination with hazing (a practice of bullying in the army that is extremely common everywhere), the slightest hint of homosexuality was likely to be punished at least informally.

In independent Ukraine, criminal penalties for “sodomy” were abolished in 1991. The legal framework of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, as the successor to the Soviet one, also does not contain explicit prohibitions to serve. In 2016, Ilovaisk veteran Oleh Kopko was the first person to come out in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. At that time, everything was limited to an article in the media as part of the “Tolerance Journalism” project.[8] The coming out went unnoticed by the public. The second coming out in the Armed Forces of Ukraine in 2018 got better coverage. Viktor Pylypenko, a veteran of the Donbas Special Forces Battalion of the National Guard of Ukraine, did it. During Anton Shebetko’s photo exhibition “We Were Here”, dedicated to LGBT+ combatants, Viktor gave a video interview in which he talked about himself.[9] The same year, the Union of the LGBT military was formed. The following year, a column of LGBT+ military personnel and their supporters participated in the Equality March in Kyiv.[10]

Oleh Kopko

A column of LGBT military personnel at the 2019 Pride

The union makes more than a dozen different demands, including legal recognition of same-sex partnerships and inclusiveness of the LGBT+ community in army regulations and statutes. The need to regulate the rights of the partner in the event of a servicemember’s death has become more urgent during the full-scale war. In 2022, a petition to the President of Ukraine received 25,000 votes and was considered.

Article 51 of the Constitution of Ukraine explicitly defines marriage as “based on the free consent of a woman and a man,” and it is impossible to amend the Constitution during martial law, so marriage equality will have to wait at least until the end of martial law.

Despite that, there are no obstacles to introducing registered civil partnerships, a close analog of marriage. The relevant draft law, No. 9103, was registered in the Verkhovna Rada and is under consideration. However, the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine does not support it, citing Article 51 of the Constitution of Ukraine and the Internal Service Statute of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, which do not prescribe commanders to register a couple where one or both partners are military personnel. The ministry did not specify the barriers to improving the statute. The ministry also stated that there is no data on the number of servicemembers who cannot officially formalize a same-sex partnership.[11]

At the time of the study, there was a de facto ban on transgender people serving in the military. According to the 10th version of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), which is in force in Ukraine, transgenderism is classified as a personality and emotional disorder (item F64 - “gender identity disorder”). According to Article 18 of Annex 1 to the Regulation on Military Medical Examination in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, personality and emotional disorders F50-F69 are grounds for declaring a person unfit or partially fit for service.[12] However, a transgender person may still serve in the military before they begin their transgender transition and receive the diagnosis. Starting January 1, 2022, the World Health Organization recommends switching to the new ICD-11 classification, where transgenderism is moved from the group of mental disorders to the sexual health conditions called “gender nonconformity.”

In Ukraine, transition to the new classification at the time of this text has not happened yet, and the relevant changes to the regulations have not been made. Partial fitness for service in wartime allows transgender people to serve in the army. As far as the author knows, there are such cases.

People diagnosed with HIV are officially recognized as unfit or partially fit for service under Article 5 of Annex 1 to the Regulation on Military Medical Examination in the Armed Forces of Ukraine.[13]

The problem of homophobia, biphobia, or transphobia in the Armed Forces of Ukraine is being recognized gradually and slowly. Back in the early 2000s, for example, the official response of the Ministry of Defense to an information request from NGO Nash Svit stated, “There are currently no psychological support programs for gay and lesbian servicemembers in the Armed Forces of Ukraine due to the absence of this problem [...] As for positions related to personnel training and promotion, homosexuality can be considered as a limitation in conjunction with other moral and business qualities of a serviceman.”

However, the response to later requests was profoundly different, in particular in 2017 of the Main Department of Moral and Psychological Support of the Armed Forces of Ukraine: “As part of legal training of the personnel of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, issues are mandatory related to observing the rights and freedoms of servicemembers, the procedure of military service, as well as the mechanism for ensuring social and legal guarantees for these categories of Ukrainian citizens. It should also be noted that the State Program for the Development of the Armed Forces of Ukraine until 2020, approved by the Presidential Decree No. 73/2017 dated 22.03.2017, provides for the necessary conditions for a gradual change in the mentality of the military personnel of the Armed Forces of Ukraine based on European values. In order to implement the above, it is planned to amend the legislation of Ukraine to eliminate any form of discrimination in the military service.”[14]

Research on the LGBT+ situation in Ukraine’s military service

In early 2022, I conducted a mini-study of the situation for LGBT+ military personnel in Ukraine. It was the first study in Ukraine to focus on this issue, as the movement of LGBT+ servicemembers only recently emerged. However, the topic of unlawful treatment of colleagues due to homophobia or transphobia was raised by respondents of the study “Invisible Battalion 3.0. Sexual Harassment in the Military Sphere in Ukraine”, which involved one homosexual man and one transgender woman who ended their military service before transition. Back then, the respondents named problems, among others, such as harassment and prejudice against servicemembers by colleagues based on their sexual orientation and gender identity, in particular, a noticeable deterioration in attitudes toward a non-heterosexual person after coming out without any other reason for the deterioration, demonstratively unaddressed threats, and homophobic attitudes toward people suspected of homosexuality due to a lack of visible sexual attention to women.[15]

As part of the 2022 study, I conducted 10 interviews with 7 men and 3 women who belonged to the LGBT+ community and were active military personnel.[16] The respondents reported that they had personally experienced homophobia and had heard of such cases. The research methodology did not allow us to establish the actual prevalence of such cases. Still, subjectively, the respondents noted them as common, as a general norm of attitudes towards LGBT+ people. The high level of homophobia, low understanding of what homosexual orientation is, and low level of general culture create at least some discomfort in the service.

“And then you go to the canteen at lunchtime. Everyone looks at you and says, ‘Oh, it’s him, it’s that one.’ And every single day, I eat and they point at me, and they say something about me, and I hear it. Then, in the smoking room, they ask such slippery questions as ‘and what?’, ‘and who?’, like trying to surface some kind of truth, but it’s my personal business whether I want to share it or not. But I’m generally irritated that they exposed me.” (Respondent 1)

“They said ‘this is how you discredit the Army, you demonstrate to others that everyone here is like that.’” (Respondent 6)

Otherwise, a person may face dismissal, physical violence, and even incitement to suicide. The lower a soldier’s rank, the harder it is for him to be open about his orientation. Respondents do not recommend conscripts and other lower-ranking soldiers disclose their orientation at all, advising them to delete personal data from their phones, etc. Respondents now perceive homophobic problems as almost unavoidable after coming out. The military personnel responsible for moral and psychological support are currently unable to systematically provide qualified assistance to LGBT+ people due to their low general qualifications, overload with paperwork, and lack of knowledge about the specifics of the LGBT+ community, even if they want to help.

“And if it happens that everyone is against it, well, I’m putting it mildly, if the unit commanders don’t approve it, the department and so on, it is very difficult. It will be very, very hard, and no one will help you with this issue.” (Respondent 3)

“But I will say this, if there was direct harassment, well, I probably wouldn’t have lasted long. I would have started to break down.” (Respondent 4)

“What exactly will happen: he can be beaten, he can be humiliated, he can be humiliated in front of the whole platoon, he will simply not be able to live here, he will be verbally insulted. I don’t know... I just haven’t encountered it directly, but, in principle, I understand from what other guys say about what they would do to a gay man - it’s just horrible.” (Female Respondent 7)

Inclusivity for LGBT+ people in the military workplace

The Hague Center for Strategic Studies defines inclusion as a guiding principle that maximizes the benefits and minimizes the risks of diversity.[17] It is the best option among other guiding principles compared to acceptance, tolerance, exclusion, and persecution. The Center identifies the following types of inclusive policies:

- Leadership, training, code of conduct. The top-down approach works best in the army because of its hierarchical nature. Policy coming from the leader counteracts the risks of harassment. Mutual respect should be explicitly stated in the statutory documents.

- Support networks and mentoring. Associations that provide support to their members can be a resource. Such associations may even be funded from the state budget in some places.

- Combating discrimination. The prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity should be explicitly stated and enshrined in law.

- Recognition of relationships. The state should recognize same-sex relationships through the institution of marriage and/or registered partnerships. This point is especially relevant for today’s Ukraine, where active hostilities are taking place.

- Recognition of gender. Transgender individuals may wish to have their gender officially recognized by the state and other institutions, including the army. Procedural issues related to changing documents, access to hormone replacement therapy, and surgical sex reassignment procedures should be consistent with the regulatory framework and internal logic of military service.

The Center notes that these practices are currently being implemented in different armies around the world in an unsystematic manner and are not tested for effectiveness, so it is difficult to identify any countries whose best practices are worth emulating. In contrast, the center’s research team formulated three strategies to provide a more focused vision.

- Mainstreaming - developing new inclusion policies and increasing the inclusiveness of old policies

- Managing - dedicated effort and an accountability approach

- Measurement - tracking and evaluating progress

In 2014, the Hague Center for Strategic Studies ranked the armies of 103 countries in terms of inclusiveness towards the LGBT+ community. Ukraine was ranked 52nd in this index (the study was conducted one time, so the index has not been updated). New Zealand ranked first, followed by the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Australia. According to the study, including LGBT+ people in the military correlates with the degree of human development and indicators of democracy and, of course, with the general public acceptance of the LGBT+ community. In some countries, such as Croatia, Israel, or South Africa, LGBT+ people are better accepted in the military than in society at large.

Illustrations: Tom of Finland, Time, Deutsche Welle, Queer BW, Radio Liberty, Suspilne, Hromadske.

This publication was prepared by the expert resource Gender in Detail with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

The Resilience Program is a 30-month project funded by the European Union and implemented by ERIM in partnership with the Black Sea Trust, the Eastern Europe Foundation, the Human Rights House Foundation and the Human Rights House in Tbilisi. The project aims to strengthen the resilience and effectiveness of war-affected CSOs and civil society actors affected by the war in Ukraine, including independent media and human rights defenders.