Translated from Ukrainian by Iryna Malishevska.

Introduction

Women made up almost half of the people who participated in EuroMmaidan. Due to gender stereotypes, women were assigned secondary roles (cooking and cleaning, entertainment, etc.) and men were assigned combat roles (barricades, guards). However, in reality, there was not much segregation in tasks that men and women were engaged in. Women were also involved in forceful confrontations and formed women’s units, while men did cooking and cleaning.

The three months of EuroMmaidan and the five years of the ongoing war demanded so many financial and human resources from society that men alone would not have been able to provide. In fact, the mobilisation of society for the new important processes was a structural factor in the transition of men’s and women’s social roles. Philosopher Tamara Zlobina calls this process ‘gender decay’[1]—when the old gender roles of Barbie (the glamorous woman) and Berehynia (women who perform reproductive work at home) fade away, while emancipated images of femininity become established in the public consciousness as a new norm.

Women left Euromaidan to join volunteer battalions and became volunteers, social activists, and politicians. They are changing their domains gradually but consistently. In this article, you will learn about the changes that have taken place in the Ukrainian army in terms of gender roles.

UNEXPECTED WAR

On April 14, 2014, following the Russian Federation’s military operation to seize the Crimean Peninsula and introduce Russian Federation troops into Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine launched the Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO). On May 22, 2014, the law of Ukraine “On the Status of War Veterans and Guarantees of Their Social Protection” was extended to include ATO participants. On April 30, 2018, the legal status of Ukrainian combat operations to overcome Russian aggression changed: the Joint Forces Operation (JFO) replaced the ATO.

The ATO was carried out by the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), the National Guard of Ukraine (NGU), and volunteer battalions, which were grassroots military units. In fact, the volunteer units were the first wave to resist Russian aggression before the AFU would deploy its military capabilities. Participation in the ATO as part of official armed groups took place by conscription and enlistment. Those who wanted to join could enlist officially. Over time, almost all volunteer battalions became part of the NGU or the AFU, and their members signed official contracts. To a great extent, the volunteer and official units were maintained by the volunteer movement, i.e., people who volunteered to buy all the necessary items and brought them to military units. Women played a significant role in both volunteering and volunteer battalions. What kind of army did they join?

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND: WOMEN IN THE SOVIET ARMY

It is a challenging task to provide a comprehensive overview in one article of Ukrainian women’s participation in different armed formations at different times. So, we will focus mainly on women in the army and the background of the current situation. The immediate and most important predecessor of the AFU was the Soviet army. Its infrastructure, legal framework, and code of conduct, which are still relevant today, were inherited by the AFU.

During the civil war, Communist women served at the front mainly as nurses and political instructors, but rarely in combat positions (this was also relevant for civil party work, which was mainly paperwork or administrative work in low-level positions, while only women from women’s sections reached leadership positions)[2]. Aleksey Tolstoy’s novel The Viper (1928) and its screen adaptation (1965) show a female combatant being bullied in peacetime so that she takes to murder.

Film frame from The Viper (1965), starring Ninel Myshkova

Further gender strategies of the Soviet authorities were aimed both at the emancipation of women and their exploitation as an economic resource by the totalitarian political regime. The 1936 Constitution of the USSR granted equal rights and obligations to work to women and men, and the proportion of women in industry increased significantly between 1920 and 1930: from 27% in 1927 to almost 42% in 1939[3].

Historian Kateryna Kobchenko points out that women’s active participation in World War II had been rooted in pre-war strategies to mobilise women for wage labour in industry, including heavy industry, sport, and aviation, which were components of the overall female emancipation project, and also in defence and first aid training, which were from then on mostly women’s responsibilities. The latter two spheres are in fact reproductive labour: it does not create any new state of affairs but reproduces the existing and necessary one. The assignment of this reproductive labour to women has been largely preserved in further regulations.

Although the authorities did not have a clear-cut program to involve women specifically in military activities, generally they were not against women volunteering for military service[4]. In 1942, the USSR conscripted women en masse for service as liaison officers, drivers, telephonists, intelligence officers, machine gunners, and cooks. Apart from the hundreds of thousands of conscripted women, women participated widely as volunteers[5].

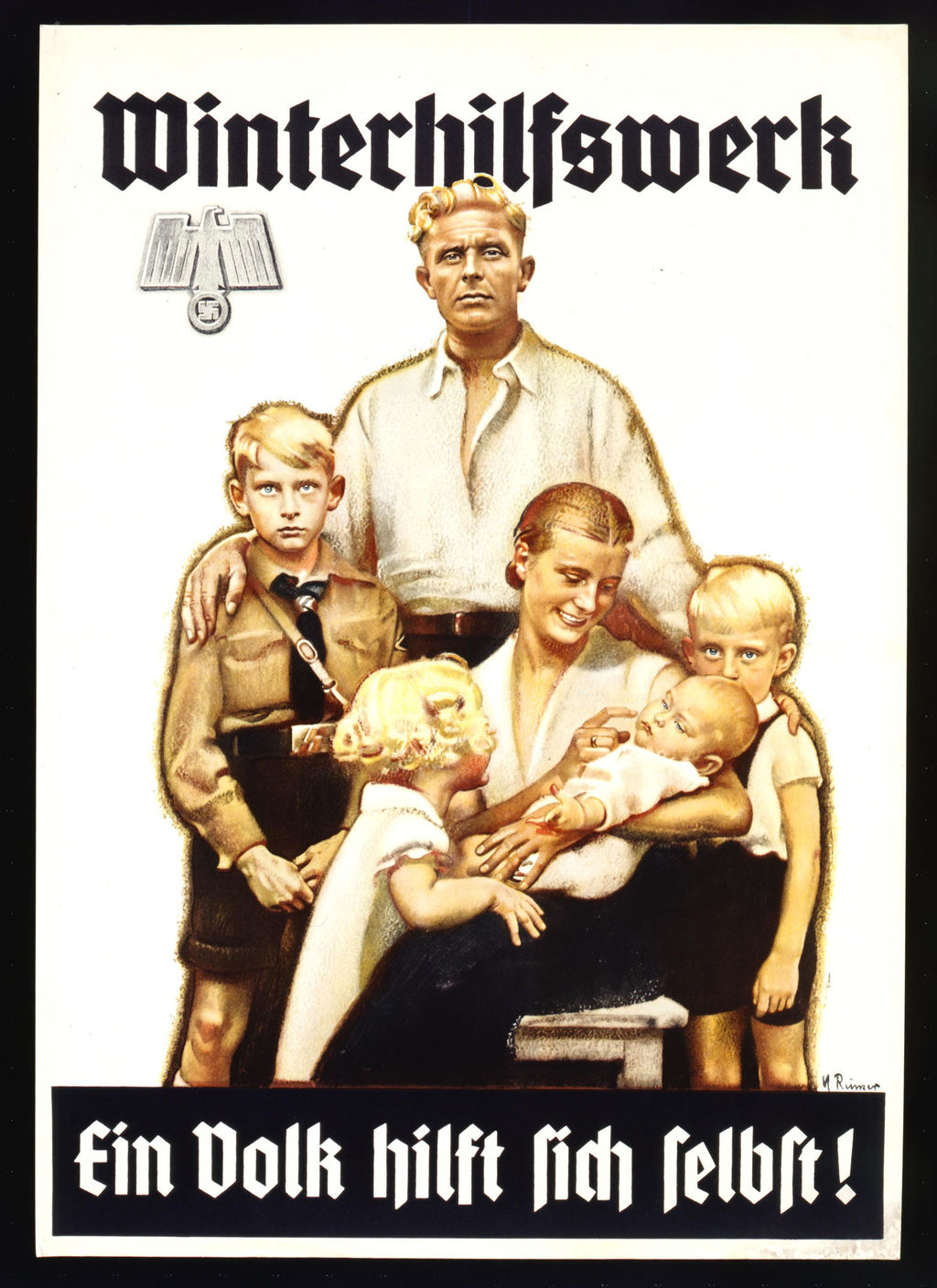

It should be noted that the situation on the other side of the front was fundamentally different from the Soviet reality. Women’s role as mothers was firmly established in the Third Reich. “As a man, I would burn with shame if a single woman went to the front in the event of war. A woman has her own battlefield. By giving birth to a child, she is fighting a battle for the whole nation. Where a man stands for the people, a woman stands for the family,” Hitler declared in his speech before the National Socialist Women’s Congress[6]. However, the reality was a bit different: women worked in service positions in concentration camps and even as radar operators in observation towers.

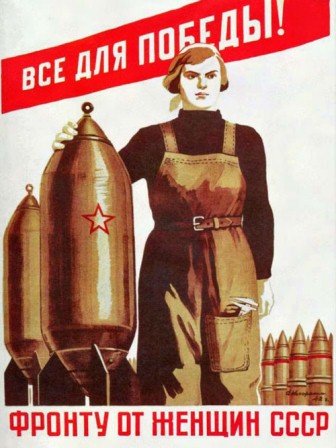

Posters portraying a woman’s role during national socialism

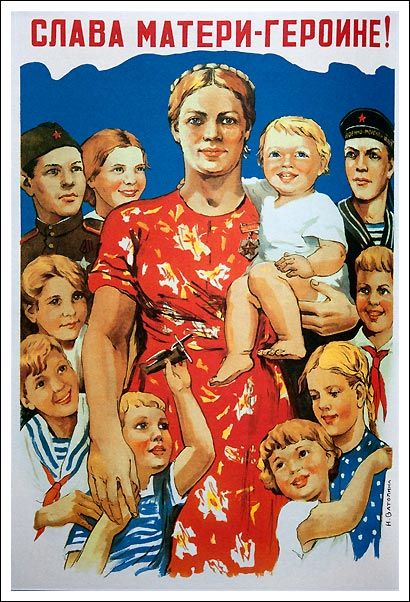

Soviet posters on women and children

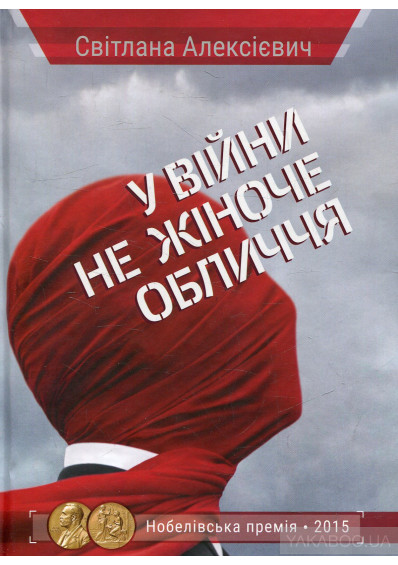

As for the USSR, the lack of a clear program about women’s participation, apart from the aviation industry, meant, above all, that women were not recognised for their contribution to the war, which led to the social stigmatisation of front-line women after their discharge. Svetlana Alexievich, in her book The Unwomanly Face of War, shows the women’s and humanistic dimension of the war and particularly emphasises the theme of the return to peacetime life. I would like to quote at length.

“There was no one I could tell that I had been wounded, that I had a concussion. Try telling it, and who will give you a job then, who will marry you? We were silent as fish. We never acknowledged to anybody that we had been at the front. We just kept in touch among ourselves, wrote letters. It was later that they began to honor us, thirty years later...to invite us to meetings...But back then we hid, we didn’t even wear our medals. Men wore them, but not women. Men were victors, heroes, wooers, the war was theirs, but we were looked at with quite different eyes. Quite different...I’ll tell you, they robbed us of the victory. They quietly exchanged it for ordinary women’s happiness. Men didn’t share the victory with us. It was painful...Incomprehensible...”[7]

“We went to Kineshma, that’s in the Ivanovo region, to his parents. I went there as a heroine; I never thought a frontline girl could be greeted like that. We had been through so much, had saved so many children for their mothers, husbands for their wives. And suddenly...I learned about insults, I heard offensive words. Before that, all I heard was ‘dear nurse,’ ‘darling nurse.’ And I wasn’t common-looking, I was pretty. I had a brand-new uniform. In the evening, we sat down for tea. His mother took her son to the kitchen and wept, ‘Who have you married? A frontline girl...You have two younger sisters. Who will want to marry them now?’ And today, when I remember that, I want to weep. Picture this: I had brought a record, I liked it a lot. It had these words: ‘and you sure have the right to go around in fancy shoes...’ It’s about a frontline girl. I played it, and the older sister came and broke it right in front of me, meaning, you have no rights. They destroyed all my photographs from the front...Ah, my precious one, I have no words for that. No words...”

“It was only decades later that the well-known journalist Vera Tkachenko wrote about us in the central newspaper Pravda, about the fact that women were also in the war. And that there are frontline women who have remained single, have not arranged their lives, and still have nowhere to live. And that we were in debt to these saintly women. And then, little by little, people began to pay more attention to these frontline women. They were 40 or 50 years old, and they lived in dormitories. Finally, they began to give them individual apartments. My friend...I won’t mention her name, she might suddenly get offended...An army paramedic... wounded three times. When the war ended, she went to medical school. She had no family; they had all been killed. She lived in great need, had to scrub floors at night for a living. She didn’t want to tell anybody that she was handicapped and was entitled to benefits. She tore up all her certificates. I asked her: ‘Why did you tear them up?’ She wept: ‘And who would have married me?’ ‘Well, so,’ I said, ‘you did the right thing.’ And she wept still louder: ‘Those papers would be very useful to me now. I’m very ill...’ Can you imagine? She wept.”[8].

Post-war memorial culture did not eliminate female veterans entirely. For example, the poems of veteran poet Yulia Drunina were widely published. In fact, she was the only representative of the female veteran voice in literature.

I’ve seen hand-to-hand combat so many times,

Once in person. And a thousand times in my dreams.

Those who say war is not scary

Know nothing about it.

“I’ve seen hand-to-hand combat so many times…” (1943)[9]

Yulia Drunina. 1956

Individual cases of women’s participation in combat as saboteurs (Zoya Kosmodemianskaya) and underground fighters (Raisa Okipna, the Young Guards Ulyana Gromova and Lyubov Shevtsova) were glorified. However, the dominant forms of commemorative practices, such as Victory Day marches and inviting veterans to schools for speeches, effectively eliminated women. Historian Olga Nikonova points out that the maximum ritualised and repetitive nature of the latter, due to its educational function, made it impossible to present any ideas or experiences different from the official ones[10]. At the same time, even official figures state that 800,000 women took part in the war on the side of the USSR. As Nikonova suggests, front-line women became a ‘figure of silence’ after Mikhail Kalinin, the head of the USSR Supreme Soviet Presidium, recommended in his speech of July 1945 that women not boast of their merits. Women’s visibility was back only after Svetlana Alexievich’s book was published in 1984. The first edition was noticeably censored, but even that version had a distinct anti-totalitarian dimension and focused on the particularities of the female respondents. In the later uncensored edition, Stalinism was already explicitly criticised.

World War II resulted in a huge loss of life, so even before the war ended, measures to encourage the birth rate were introduced. For example, the decree of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet “On Increasing Public Support to Pregnant Mothers, Mothers with Many Children, Single Mothers, Enhancing the Protection of Motherhood and Childhood, Proclaiming ‘Heroine Mother’ as the Title of Highest Distinction, and Establishing the Order of Maternal Glory and the Medal of Motherhood”, was introduced on July 8, 1944, increasing financial support for mothers.

Posters from years portraying mothers as heroines

Sometime in the 1960s, the science of Soviet labour law gained gender-sensitivity. In 1970, Vera Tolkunova defended her doctoral thesis “Social and Legal Problems of Women’s Labour in the USSR.” Tolkunova’s findings were largely used in the Labour Codes of the union republics, where separate sections on women’s labour were introduced that included framework principles for restricting women’s labour at night, etc[11]. The need to restore and maintain the birth rate was emphasised and thus reproductive labour was assigned to women, while the army was left to men.

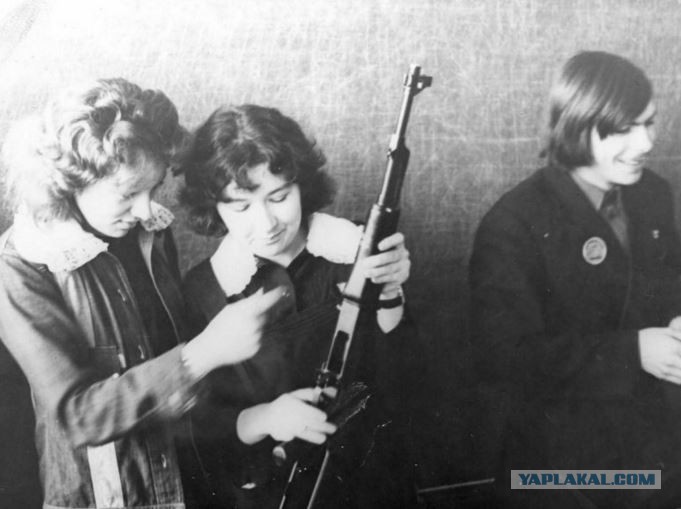

In 1968, Initial Military Training classes were introduced in secondary schools and vocational schools. Boys and girls were taught separately, girls being trained as voluntary aid detachment personnel, while boys were taught how to shoot. The basics of civil defence were taught to both genders. This separation strengthened gender distribution and established a rather low “glass ceiling.” Military service and career development became accessible for women only on a limited list of professions like psychologist.

Civil defence classes

This logic exploited women and men not only as human resources of the militarised state but also by assigning them mandatory and fixed gender roles with no regard to personal desires and needs. While men’s achievements and the right to a career were at least recognised, women were deprived of this as well, adding an extra dimension to the exploitation.

UKRAINIAN POST-SOVIET ARMY

Women have served in the AFU since Ukraine proclaimed its independence [in 1991].

Expert Natalia Dubchak notes that it was mostly wives, daughters, and other relatives of servicemen who did military service in the AFU [12]. Unfortunately, this topic lacks official data and research. Dubchak, based on her own analysis of military service by women in the AFU in 2001-2006, points out that, while the total number of servicewomen decreased, the number of servicewomen showed a dynamic increase in all categories. Whereas in 2001, women officers accounted for 0.7% of the overall officer corps, in 2006, the rate had reached 2.25%. According to the expert, the trends of women’s representation in the defence sphere were positive, but the reason for this was not the prestige of the service, but first and foremost the reluctance of men to take up low-paid positions[13].

However, the AFU traditionally remained an extremely conservative social institution. This impacted not only gender issues. In early 2014, the army was semi-decayed. The institution itself did not receive sufficient public or state attention. It was not maintained on a functional level, not to mention reforms and strategic planning. Gender reforms in the army have become part of reforms in the security sector as a whole.

Until 2014, not only did the AFU not function properly, but they also had sold off their assets[14]. Experts noted that the military administrative reform of 2013 was not useful for the army[15]. Corruption and nepotism in the army did not benefit women as a low-resource population group. The structure and logic of the army had not changed since Soviet times and also relegated women to service and non-prestigious roles. They were not offered any other opportunities.

The Temporary List of military occupational specialties and designated positions for enlisted personnel and servicewomen and remuneration tables for positions were approved by Order of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine № 337 of May 27, 2014, and offered staff positions for female privates, sergeants, and petty officers. This list is not supported by any previous documents, so it turns out that it was not until the war started that the proportion of military registration specialties, military ranks, and positions were regulated at least to some extent.

Women were assigned to military occupational specialties according to the Decree of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine “On the Approval of the List of Specialties for which women with relevant training may be registered for military service” of October 14, 1994. The list included seven eloquent categories: Medical; Communication; Computer Engineering; Optical and Sound Measurement and Metrology; Cartography, Topogeodesy, Photogrammetry, and Aerial Photography; Printing; and Film and Radio Mechanics. This was the only range of jobs open for women who wanted to be registered for military service.

This paradigm of women’s participation in the Ukrainian Armed Forces was rooted in the consistent Soviet concept of protecting motherhood and childhood. According to this concept, motherhood was a great value for the whole society. This imposed corresponding restrictions on women’s work in general, with no regard to whether a woman wanted to have a child. The new Ukrainian labour protection paradigm continued to exclude women from a large number of physically demanding jobs. The legal framework designed in the Soviet times imposes restrictions on women that exclude them from many professions, both civilian and military.

Section XII of the Labour Code regulates women’s labour. In particular, Article 174 of the Labour Code states that “the employment of women in difficult jobs and jobs with harmful and unsafe working conditions, as well as in underground work, except for some underground work (non-physical work or work in sanitation and domestic services) is prohibited. It is also prohibited to involve women in lifting and transferring heavy things, whose weight exceeds the established norm for women.” Article 175 of the Labour Code prohibits the hiring of women for work at night. These regulations are still in force.

In practice, this meant that women did the same work as men, but without being officially employed. Iryna Kogut’s 2013 study of women’s working conditions in mines revealed that, despite claims that women cannot and should not perform hard and harmful “male” work, in reality they perform it unofficially and are paid significantly less (two or three times less average at the enterprise)[16].

As a result of traditional stereotypes about men who protect women and perform productive work, while women perform reproductive work (not only giving birth and childcare, but also serving), the distribution of positions available to men and women in the Armed Forces of Ukraine was clearly gendered, similar to the civilian labour market. A woman could be a medic, a cook, a seamstress, responsible for the bathhouse, and could perform other kinds of reproductive work, but could not be a gunner, a grenade launcher, or a crew commander, i.e., could not hold command and combat positions. Limited access to the military education required for officer positions resulted in a “glass ceiling.”

The first small steps toward gender equality in the Armed Forces of Ukraine were taken back in the mid-2000s. In particular, one of the Deputy Ministers of Defence became responsible for ensuring equal rights and opportunities for women and men in accordance with the Presidential Decree from July 26, 2005, “On Improving the Work of Central and Local Executive Authorities to Ensure Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men.” Students studying psychology and political science at the Military Institute of Kyiv National Taras Shevchenko University were given a 36-hour course on Gender Studies[17]. However, this was not nearly enough.

Nadiya Savchenko

Shortly before the war began, servicewoman Nadiya Savchenko managed to overcome the ban on women serving as pilots and navigators, but, apparently, this was not enough. This young woman tried to enter Kharkiv Air Force University four times and succeeded only after her enlisting in the army as a radio operator and serving as a paratrooper and gunner in the Ukrainian peacekeeping contingent in Iraq. She requested the defence minister’s personal permission to become a pilot and finally received it.

WOMEN AS AGENTS OF CHANGE

The first wave of volunteer engagement in the war began in the spring of 2014. Society reacted faster than the state and a new window of opportunity opened up for women. Despite the belief of some feminists that wars are just “macho games”[18], many women took an active political stance by volunteering for combat. They could be driven by general civic or personal motivation.

Viktoriia Dvoretska, a female member of the Aydar volunteer battalion, shares her early involvement in combat operations:

“I can’t remember now whether we called ourselves volunteers or anything else at the time. I don’t remember anyone doubting whether we should go to the Donbas or not. But I remember us green as grass, funny, confused, dear and sincere. We were running forward in sports shoes and with a gun (if you were lucky).

“I remember the times when it was the greatest honour to defend your homeland. I remember all the first forming-ups. I saw with my own eyes how you became real soldiers, professionals, and many of you are still on the front line.”[19]

Yulia Tolopa (Valkyrie) is a Russian who moved to Ukraine at the age of 18 for her personal convictions and went straight to the front. After maternity leave, she returned to service. She tried for five years to obtain Ukrainian citizenship and it was not until June 28, 2019, that the Ukrainian president signed a decree granting citizenship to Tolopa and other foreign volunteers.

Yulia Tolopa. Photo from her Facebook page

Liana Krombet, a former employee of Oshchadbank’s call centre, wanted to join the army from the beginning, but was able to officially join the service only in February 2015. A year later she signed a contract with the National Guard of Ukraine as a gunner[20].

Professional journalist Olena Maksymenko spent one rotation with the Mykola Pyrohov First Volunteer Mobile Hospital and four rotations with the Hospitallers medical battalion of the Volunteer Ukrainian Corps. During her service, she performed not only medical duties but also documented the battalion’s activities. Later she returned to military journalism, which is her main specialisation[21].

National Alliance activist Maiia Moskvych fought from the early days of the war in several battalions. After her discharge, she won gold medals in individual and team events at the Invictus Games, the international sports competition for disabled veterans held in Australia in 2018.

Maiia Moskvych. Photo from her Facebook page

Olena Herasymiuk was volunteering since the beginning of the war, and after her cousin was killed in 2018, she decided to enlist.

Olena Herasymiuk. Photo from her Facebook page

These and other women have all become active agents of change breaking patriarchal stereotypes. In 2019, the Ukrainian Women’s Veteran Movement was born. This is a grassroots initiative by women who had returned to civilian life but were keen to stay active in order to “provide women veterans with support, communications, and consolidation.”[22] Another women’s project is Veteran Diplomacy, designed to spread the word in other countries about what is happening in Ukraine.

“Ambassador” Veteran Diplomacy Club, the first mission to NATO Headquarters (Brussels), 2019

There are women among the killed. On July 2, 2019, military medic Iryna Shevchenko, who was evacuating the wounded, was killed near the village of Vodiane. On April 2, 2019, machine gunner Yana Chervona died when an enemy missile hit her dugout. She was posthumously awarded the Order of Bohdan Khmelnytsky III Degree.

Iryna Shevchenko. Photo from her Facebook page

Yana Chervona. Photo from her Facebook page

THE NEEDS OF WOMEN VOLUNTEERS AND “THE INVISIBLE BATTALION”

The Invisible Battalion project was launched in the summer of 2015, a year later after the armed conflict started. It was an attempt of servicewomen to outline the problems they face in their service and to find solutions. The Invisible Battalion advocacy campaign included sociological research[23], a photo series for exhibitions, and working with stakeholders. The research found that women face legal obstacles in their service and have no special conditions of service, so the need for full gender equality in the security sector and breaking the “glass ceiling” became a matter of public debate.

Invisible Battalion proto project

The Law of Ukraine “On the Status of War Veterans, Guarantees of their Social Protection” contains a long list of benefits for ATO / JFO participants. However, the appropriate status is required to access these benefits, which women who were not formally registered were unable to obtain. Women who were actually in command and combat positions but were registered in service positions faced similar difficulties.

Legal invisibility led to infrastructural invisibility, which resulted in a lack of uniforms, shoes, gynaecological care, hygiene supplies, etc. Only in 2017 did the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine take care of underwear for female military personnel, but the design proved to be of extremely poor quality and not designed for intense physical activities[24]. Formalising volunteer battalions helped more servicewomen than before to enlist, but changes in the logistical paradigm did not keep pace with the number of women who wanted to serve in the army.

“THE INVISIBLE BATTALION” ADVOCACY CAMPAIGN AND CHANGES IN LEGISLATION

The Invisible Battalion is an example of a grassroots movement that managed to establish cooperation with the authorities and reach vitally important political results in just a few years, which is a relatively short period of time. This was achieved thanks to Maria Berlinska, an aerial reconnaissance drone operator and activist, and the Ukrainian Women’s Fund and UN Women Ukraine.

Maria Berlinska on the left

On June 3, 2016, the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine amended the temporary list of staff positions for privates, sergeants, and petty officers, approved by Order of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine № 337 of May 27, 2014. The list of combat positions for female enlisted service members was expanded significantl, by over 100 jobs.

The “Equal Opportunities” Inter-factional Parliamentary Association prepared Draft Law № 6109 “On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Ensuring Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men in the Armed Forces of Ukraine and Other Military Formations.” The President of Ukraine signed the law on October 12, 2018. The law establishes a framework principle of equal rights and opportunities for women in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, although it does not work out in detail concrete principles. The Law of Ukraine “On Military Duty and Military Service” received an explicit provision that women perform military service on an equal footing with men, which provides for admission to military service under contract, assignment to positions, gaining military ranks, performing military service tasks, etc. Equal age limits for women and men for enlisting in contracted military service were established (instead of the previous limits of 18-40 for women). Women who are liable for military service are no longer registered as second-class reservists. The Internal Service Statute of the Armed Forces of Ukraine removed the clause stating that women shall not be assigned to 24-hour shifts.

On December 21, 2017, the Ministry of Health of Ukraine repealed its decree № 256 that prohibited women from a list of 450 professions[25].

Ukrainian servicewomen at the Independence Day military parade, 2018

Over 20,000 women served in the Armed Forces as of the summer 2017, i.e., 8.5% of the total military personnel[26]. In one year, the number grew to 55,000[27]. According to the National Police of Ukraine, women account for 21% of all officers and 15% in patrol units. These are quite good figures, but in most cases, women occupy low-level positions. In 2018, it was only for the second time that Ukraine had a female general: Lyudmila Shugaley was appointed to the post of Major General. The first woman promoted to the rank of general (2004) was Tetiana Podashevska, the head of the Public Relations Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs[28].

Lyudmila Shugaley was appointed Major General in 2018

However, achieving certain quantitative indicators should not be a matter of formality. The engagement of any women in the army by itself is an inadequate, if not harmful, practice.

REPRESENTATION IN THE MEDIA AND VISIBILITY OF WOMEN SOLDIERS

L’Officiel glossy magazine decided to feature Nadiya Savchenko in the column “White Shirt.” Since the servicewoman was in prison in the Russian Federation at the time and it was impossible to photograph her in a white shirt, the editors simply made a photo collage[29]. Although this was recognised as inappropriate on social networks, the publication was released, and the editors did not admit their mistake. Nadiya’s hunger strike was widely discussed in terms of attributing masculine traits to her, such as “a woman with balls”, “a real man”, etc[30].

As the Invisible Battalion research shows[31], the media often emphasised the friendly and caring attitude of male soldiers towards the women fighting alongside them. This is to some extent a reproduction of patriarchal roles, which suggest that men protect women, even if they all are in the same conditions. Many of the publications analysed within the Invisible Battalion research demonstrate such an attitude towards women. It expects approval from the audience, but in reality, it is a manifestation of “friendly sexism.”

According to the materials collected in the summer and autumn of 2015, three main images of women in the ATO are present in the media: a woman warrior, a caring helper, and a revolutionary. At the same time, the media provide almost no information about the special needs of servicewomen.

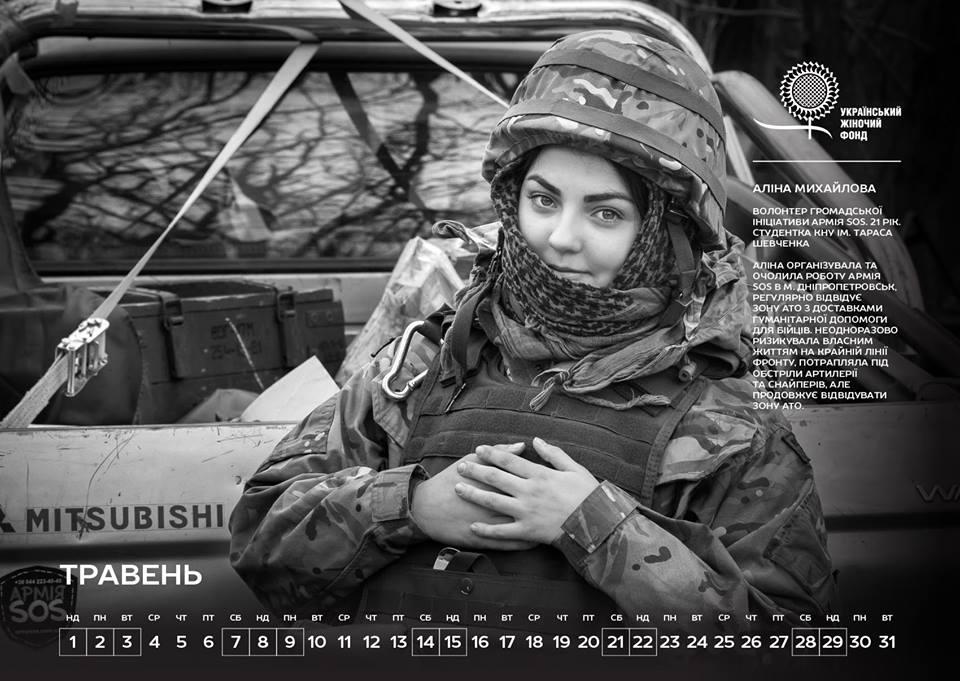

After the Invisible Battalion advocacy campaign was launched, the specifics of women’s experiences and women’s needs gradually appeared in the media. The Invisible Battalion calendar (2016), created by Mex Advertising, won the Grand Prix at the 9th National Festival of Social Advertising. In 2017, two documentaries on servicewomen were filmed, The Invisible Battalion and No Obvious Signs.

Still from the movie “The Invisible Battalion”

The first documentary focuses on six women who have fought or are still fighting in the army. The second documentary tells in more detail a story about the return to civilian life of one of these six women, Major Oksana Yakubova, a deputy battalion commander for personnel work in the 30th separate mechanised brigade.

Update from the editorial board, May 2020:

Modern Ukrainian literature has long lacked a novel with a female combatant in the East of Ukraine as a protagonist. Daughter, the debut novel by Tamara Duda published in late 2019, attracted much attention in a rather positive way. The book offers the detailed story of such a protagonist, with elements of reportage and documentary literature. Daughter was immediately awarded the BBC Book of the Year, which is one of the most respected Ukrainian literary awards. Both the book and the author have gained much attention from both the reading audience and the professional community (in particular, Oksana Zabuzhko gave very positive feedback on the book).

Another example is the female veteran reportage book Girls Cutting Their Locks, by journalist Yevgeniya Podobna. The author collected the memories of 25 women in the military who fought in the ATO in 2014-2018. Podobna also won the well-deserved Shevchenko National Prize in Publicity and Journalism (2020) for her book.

CURRENT ISSUES: EDUCATION AND REINTEGRATION

In 2014, women who served in volunteer battalions were trained on their own and in the field, but this is not enough for the institutional level. Until recently, women’s access to specialised secondary and higher military education was complicated. For example, Polina Kravchenko, press officer of the motorised infantry brigade, was rejected from the training programme for officers at the Hetman Petro Sahaidachny National Ground Forces Academy because she is a woman[32]. It was only in September 2019 that girls were granted access to education in military lyceums[33]. It is only now that restrictions are lifted on admitting females to higher military education institutions and military training units of higher education. As of today, women account for 8% of the total enrolments in higher education military institutions and military training units of higher education. At the moment, there is no strategy to increase their number.

In the summer and autumn of 2018, a team of sociologists studied Ukrainian women veterans’ return to peaceful life, which helped, among other things, to understand how the national system for reintegrating women veterans functions in practice.

Photo from the Facebook page of the Women’s Veteran Movement

The results of the research demonstrated the low quality of state employment services, medical care, and psychological rehabilitation, as well as insufficient access to the benefits granted by the Law of Ukraine “On the Status of War Veterans and Guarantees of their Social Protection.”

The path to reintegrating female veterans into peacetime life is blocked by the stigmatisation of female veterans in society, a bias towards their contribution in public security and their motivation to perform military duties (in particular, there is a stereotype that women who joined the army are either no longer good for anything else or are focused on finding a man).

Female veterans face this stigmatization not only from society (which has a bias towards male veterans, too), but also from those who work with female veterans, including doctors and employees of military recruitment offices, employment services, and social protection agencies The research (not yet been published) gives examples of how a recruitment office returned documents to women with an accompanying text that made it apparent that the women had been taken to be men, i.e., the documents hadn’t been opened. Women who returned to civilian life because of maternity leave do not have the opportunity to combine raising a child with resuming service[34].

On December 5, 2018, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine adopted the “State Target Programme on the Physical, Medical, and Psychological Rehabilitation and Social and Professional Re-Adaptation of Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) Participants and Persons Involved in National Security Measures and Defense, Repelling and Deterring the Armed Aggression of the Russian Federation in Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts, Ensuring Their Implementation, for the Period until 2022.” The programme stipulates that the specific characteristics of women and men will be taken into account in administering veterans’ needs and that the objectives and measures of the programme will be implemented in accordance with the principle of equal rights and opportunities for men and women. As of today, no information on the quality of implementing this programme is yet available.

Women’s Veteran Movement at Ivano-Frankivsk

In the summer of 2018, the Women’s Veterans Movement organised a founders’ meeting Kyiv Oblast. The movement is essential not only for defending specific women’s interests, which are currently unprotected, but also for introducing practices of participation in decision-making and advocacy.

DAY OF THE DEFENDERS AND DEFENDRESSES

The perception of the all-Ukrainian holiday of Defender of the Fatherland Day (October 14) has also changed over time. Until recently, it was a replica of February 23 (a Soviet holiday, Soviet Army and Navy Day), and by post-Soviet inertia, all men were congratulated on this occasion. After the outbreak of the war, people began to distinguish between a man and a defender.

“Many people in Ukraine began to consider Defender’s Day as a substitute for Defender of the Fatherland Day, which in the post-Soviet space became a holiday for every male. But to congratulate any random man on such an occasion is to dishonour the sacred title of Defender of Ukraine. On this holiday, we congratulate respected soldiers of the ATO and other military and law enforcement officers. We congratulate veterans of World War II and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, since both of them fought against the enemies to protect their native land. We congratulate the employees of the defence industry and in general all those working to meet the needs of the army. We congratulate volunteers.”[35]

The increasing visibility of women in the security sector brought more changes to this interpretation. Women who were involved in volunteer work and military service also acquired the right to be called Defenders of the Fatherland, so society began to recognise and discuss it.

“October 14 should be called Day of Defenders of Ukraine. It is not only men who serve in the army. Officially, there are 20,000 women in the military. There are also male and women volunteers. Watch The Invisible Battalion. The name ‘Day of the Defender of Ukraine’ shifts the focus from the protection of Ukraine to a man. It’s kind of March 8 for a fella. Especially for those who have never been in combat, but are quick to join festivities.”[36]

SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE SECURITY SECTOR

Researcher Marta Havryshko argues that sexual violence in the military is generally common for various reasons: military culture, the cult of hegemonic masculinity, underrepresentation of women in the power vertical, and the attitude of commanders who conceal and cover up crimes. Havryshko is convinced that the victims also contribute to silencing abuse because they are ashamed and afraid of being stigmatised, persecuted, and accused of slander.

Havryshko shared the experience of one respondent, a combatant who was first fighting in a volunteer battalion and then in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The respondent points out that women are vulnerable in their relations with commanders, especially male commanders of the older “Soviet” generation: “They thought that girls came to war to entertain them... They prevent women from fighting.”[37]

There are no open official statistics on sex crimes in the ATO/JFO zone. However, from time to time, individual cases make it into the media, such as the rape of a 24-year-old woman by two enlisted servicemen in a unit at the Yavoriv training ground in May 2016[38]. There is no special system for countering and preventing sexual violence in the ranks of the AFU and National Guard yet. Female members of the security sector should have a mechanism to safely file complaints against their colleagues in cases of sexual violence (for example, to complain not directly to their commander, who may be the abuser, but to a person specifically authorised to receive such complaints and conduct internal investigations. However, if this person is a man who is not well informed about the issue and does not take it seriously, it will also not be resolved). This applies not only to rape but also to sexual harassment. There are no data on incidences of the problem, understanding of this issue is limited and there are no formalised processes for effectively filing and responding to such complaints. This has a negative impact on the internal culture within security sector institutions and does not encourage more women to join the military.

There have been several known cases when women reported sexual harassment. For example, Lieutenant Valeria Sikal reported sexual harassment by her commanding officer Colonel Viktor Ivaniv. The woman alleged that he tried to hug and stroke her and explicitly stated that she had to satisfy him sexually. The lieutenant suffered from harassment for almost a year and later had to move to another unit. Journalists found out that at least eight women had suffered from this man’s harassment[39]. However, he was not punished; on the contrary, he was promoted to a member of the AFU General Staff[40].

WOMEN AS WAR VICTIMS

According to some estimates, two-thirds of internally displaced persons (IDPs) are women. Often, displaced women are the only breadwinners and caretakers of children and elderly family members. Women suffer from unemployment more often than men and have limited access to employment. In general, internally displaced women experience multiple discriminations and are more economically vulnerable than male IDPs, according to research conducted by the Office of the Ukrainian Parliamentary Commissioner for Human Rights in partnership with NGOs in the autumn of 2017[41].

Women in a war zone are also a vulnerable group, including facing the risk of sexual violence. A report by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) states that cases of sexual violence in the war zone in Ukraine occur on both sides of the front line. In both non-government-controlled and government-controlled areas, rape remains largely uninvestigated and unpunished.

As for the government-controlled areas of Ukraine, the OHCHR has reported cases of sexual violence and threats in the detention of separatist suspects, with the aim of punishing, humiliating, or receiving a plea. While the victims of such acts were mostly young men, threats were also made against women and their family members. Similar crimes have been documented in non-government-controlled areas: militants of the self-proclaimed republics have used sexual violence against detained ideological opponents (citizens with a pro-Ukrainian stance). Women, both civilians and humanitarian workers, are also harassed at checkpoints. Most of the victims have to cross the contact line on a regular basis and therefore are usually afraid to report such cases. In addition, the victims of such crimes most often lack access to quality psychological and medical care[42].

In the war zone, the number of women involved in commercial sex work has increased significantly, by at least 20%, according to expert observations. This was due, in particular, to displaced women and women who under more favourable circumstances would never have engaged in the business. With the onset of military operations, UAF combatants became the main source of income for many female sex workers. Military first aid kits do not include STD protection, so the risks of infection have greatly increased for both parties of such contact[43].

INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE AND NATO STANDARDS

Ukraine recognises the importance of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security, adopted in 2000. It focuses on women’s military service and gender-based violence during military conflicts. There was a need for such a document because women, on the one hand, suffer disproportionately from military conflicts and their consequences and, on the other hand, are underrepresented in decision-making processes within national, regional, and international institutions and mechanisms for conflict prevention, management, and resolution. The Resolution does not require ratification but obliges a UN member state to develop a national action plan for its implementation. In February 2016, Ukraine approved a National Action Plan (NAP) through 2020. Ukraine was the first country to adopt such a document during an armed conflict. In particular, the NAP stipulates that by 2020, the share of women in decision-making positions in security, defence, and law enforcement agencies is to increase to 10%, and the share of female members in negotiation groups is to increase to 30%[44].

The Ukrainian NAP has certain limitations. The state does not allocate enough funds to implementation the NAP and puts the burden of funding it mainly on civil society and international organisations. Another flaw of this document is that it is rather vague and is aimed at monitoring problems rather than practical solutions to them. However, the importance of this document is that it can be referred to when implementing projects aimed at achieving gender equality or other specific interests of women.

In order to implement Resolution 1325 and improve cooperation with the community, security sector institutions should conduct gender audits on a regular basis. Such audits should include a review of the institution’s performance in a number of indicators, including operational effectiveness, policy and planning, accountability and monitoring, human resources management, and institutional culture. Excellence in all of these indicators should be a strategic objective for all security sector institutions in Ukraine. In the case of a long-term response to military aggression, involving women’s resources is not only a matter of justice but also of effective warfare.

NATO Military Members

NATO’s internal documents include Guidelines on Gender Mainstreaming (2007); Military Guidelines on the Prevention of, and Response to, Conflict-Related Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (2016); and many others. These documents explicitly state that a person’s gender is socially constructed and acquired, therefore can be changed and that the ultimate goal of gender mainstreaming is to achieve gender equality so that women and men benefit equally while inequality disappears. Four guiding principles for actively pursuing a diversity policy at NATO Headquarters are:

- Ensuring fairness in recruitment and promotion;

- Ensuring the high quality of NATO personnel;

- Respecting the diversity of all Alliance members; and

- Agreeing only to set goals and use methods that embody a reasonable challenge.

CONCLUSIONS

In 1996, sociologist Johan Galtung introduced the dichotomy of “negative peace” and “positive peace”, with “negative peace” meaning the absence of violence and war, for example when a ceasefire comes into effect, while “positive peace” is a more complex concept: rebuilding lost connections, establishing social institutions, and resolving a conflict in a constructive way. This concept was actively used in peace studies until Peter Wallensteen, researcher of strategic peacebuilding, introduced the concept of “quality peace” in his book of the same name[45]. By this term, he implies a set of strategies to ensure that ended hostilities would not repeat and insists on cancelling the dichotomy between “negative” and “positive” peace.

For Ukrainian society, the term “peacebuilding” is tainted by its manipulative use in Russian propaganda; however, the neutral meaning of the word should also be considered. Building “quality peace” implies not only restoring Ukrainian authority over territories that are not temporarily under Ukraine’s control but also establishing a comprehensive system of defence against new attempts at aggression.

Institutional changes in Ukraine’s army only gained momentum when the ATO started. The post-Soviet army inherited the Soviet paradigm, and only the urgent need for functional combat units led to a sharp move towards efficiency. The role of gender equality is important precisely for an effective army, since stereotypical and discriminatory attitudes towards women preclude using their skills and involving their human resources.

As of today, the level of gender equality in the Ukrainian Armed Forces and the wider security sector has improved significantly since 2014. Important positive changes have taken place in the legal framework and public perception. A gender-sensitive approach is gradually being introduced in the security sector, and it is worth noting once again that servicewomen fought for these changes, and these changes were not granted to them by the authorities from the top-down. The status of women in the security sector must continue to improve. The special needs of servicewomen and women veterans have not been yet fully met.

Let me summarise the recommendations for the state:

- Ensure the accessibility of specialised secondary and higher military education for women, not only legally, but actual access;

- Provide veterans who have served in volunteer battalions with a war veteran certificate and all the benefits deriving from this status;

- Develop quality psychological (including psychotherapeutic and psychiatric) rehabilitation programmes for veterans, and additionally for families of ATO/JFO participants;

- Continuously perform a needs analysis for social protection among veterans;

- Introduce the corresponding amendments into the National Action Plan on UN Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security and allocate sufficient funding for its implementation.

The gradual changes in the logic of army building and structure that we are witnessing in real time are profound and large-scale. Soviet and post-Soviet inertia was the reason why the “pre-Maidan” army remained patriarchal. The urgent need for a new type of quality army led to the recruitment of motivated and, as far as possible, qualified women, which had an overall positive impact on the security sector and on gender equality. These development processes are still ongoing five years after the outbreak of war.

Developing “quality peace” for Ukraine should include active reform of the security sector, which also involves developing gender sensitivity at the sector level in general and individual institutions in particular. Qualified workers of both genders should not be prevented from doing their jobs effectively.

[1] Лекція «Гендерний розпад» // www.youtube.com/watch?v=RN7-9PVzJYc

[2] See: Clements, Barbara Evans. Working-Class and Peasant Women in the Russian Revolution, 1917–1923 // Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. — 1982. — Vol. 8. — № 2. — Р. 215–235.

[3] See: Лушников, Андрей. «Женский вопрос» и отечественное трудовое право: историко-правовой очерк / Актуальные проблемы российского права. — 2015. — № 3. — С. 182–189.

[4] See: Кобченко, Катерина. Жінки як військовий ресурс тоталітарної влади: радянські гендерні стратегії воєнного часу. / Жінки Центральної та Східної Європи у Другій світовій війні: гендерна специфіка досвіду в часи екстремального насильства. — К., 2015. — С. 61–78.

[5] Никонова, Ольга. Женщины, война и «фигуры умолчания» // magazines.russ.ru/nz/2005/2/ni32.html

[6] Quoted after: Моссе, Джордж. Нацизм и культура. Идеология и культура национал-социализма // propagandahistory.ru/books/Dzhordzh--Mosse_Natsizm-i-kultura--Ideologiya-i-kultura-natsional-sotsializma/18

[7] Svetlana Alexievich. The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II. Translated by Richard Pevear, Larissa Volokhonsky. Random House Publishing Group, 2017

[8] Ibid.

[9] 45parallel.net/yuliya_drunina/stihi/#ya_stolko_raz_vidala_rukopashnyy

[10] Никонова, Ольга. Женщины, война и «фигуры умолчания» // magazines.russ.ru/nz/2005/2/ni32.html

[11] See: Лушников, Андрей. «Женский вопрос» и отечественное трудовое право: историко-правовой очерк // Актуальные проблемы российского права. — 2015. — № 3. — С. 182–189.

[12] See: Дубчак, Наталія. Жінки у Збройних Силах України: проблеми ґендерної політики // Стратегічні пріоритети. — 2008. — № 4 (9). — С. 187–192.

[13] Ibid.

[14] apostrophe.ua/ua/article/politics/government/2016-09-03/massovyie-hischeniya-v-armii-o-chem-umolchala-genprokuratura/7120

[16] Когут, Ірина. «Давно вже є закон, що жінок на шахті нема... Ну як же нема, коли ми є!» // commons.com.ua/uk/davno-vzhe-ye-zakon-shho-zhinok-na-shahti-ne

[17] See: Дубчак, Наталія. Жінки у Збройних Силах України: проблеми ґендерної політики // Стратегічні пріоритети. — 2008. — № 4 (9). — С. 187–192.

[18] feministki.livejournal.com/3371586.html?thread=204721218#t204721218

[19] www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=2150170478382572&id=100001689238587 (link no longer available)

[20] theukrainians.org/lyana-strilets

[21] www.opendemocracy.net/ru/nevidimiy-batalyon

[22] www.facebook.com/UkrainianWomenVeteranMovement

[23] Марценюк Тамара, Квіт Анна, Гриценко Ганна. «Невидимий батальйон»: участь жінок у військових діях в АТО (соціологічне дослідження). — К., 2015 // www.uwf.org.ua/files/nevydymy_batalion_ukr_full.pdf

[24] Мацко, Ольга. Лифчики раздора. В Минобороны забыли, как выглядит женская грудь // www.dsnews.ua/society/lifchiki-razdora-v-minoborony-zabyli-kak-vyglyadit-zhenskaya-29092017154000

[25] Минздрав отменил перечень запрещенных для женщин профессий // 112.ua/politika/minzdrav-otmenil-perechen-zapreshhennyh-dlya-zhenshhin-professiy-425982.html

[26] В українській армії служать 20 123 жінки, — Ірина Геращенко // censor.net.ua/ua/news/443531/v_ukrayinskiyi_armiyi_slujat_20_123_jinky_iryna_geraschenko

[27] В українській армії служать 55 тис. жінок, — Порошенко // censor.net.ua/ua/news/3091255/v_ukrayinskiyi_armiyi_slujat_55_tys_jinok_poroshenko

[28] ЗМІ написали про першу жінку-генерала в Україні. Це неправда // zaborona.com/zmi-napysaly-pro-pershu-zhinku-henerala-v-ukraini-tse-ne-pravda

[29] Белая рубашка: Надежда Савченко // officiel-online.com/lichnosti/belaya-rubashka/nadezhda-savchenko

[30] See: Гриценко, Ганна. Не мужик // povaha.org.ua/ne-muzhyk

[31] Марценюк Тамара, Квіт Анна, Гриценко Ганна. «Невидимий батальйон»: участь жінок у військових діях в АТО (соціологічне дослідження). — К., 2015 // /www.uwf.org.ua/files/nevydymy_batalion_ukr_full.pdf

[32] Щонайменше трьом жінкам відмовили у вступі на курси офіцерів через стать // povaha.org.ua/schonajmenshe-trom-zhinkam-vidmovyly-u-vstupi-na-kursy-ofitseriv-cherez-stat

[33] З вересня 2019 року дівчата матимуть можливість навчатися у військових ліцеях // www.mil.gov.ua/news/2019/03/06/z-veresnya-2019-roku-divchata-matimut-mozhlivist-navchatisya-u-vijskovih-liczeyah

[34] Марценюк Тамара, Квіт Анна, Гриценко Ганна. «Невидимий батальйон 2.0»: повернення ветеранок до мирного життя. Соціологічне дослідження. Не опубліковано.

[35] Кого не можна вітати з Днем захисника України // www.depo.ua/ukr/life/kogo-nemozhna-vitati-z-dnem-zahisnika-ukrayini-12102016130000

[36] www.facebook.com/petro.okhotin/posts/1761388107237040

[37] Гавришко, Марта. «Вони думали, що дівчата прийшли на війну, щоб їх розважати»: сексуальне насильство і армія // uamoderna.com/blogy/marta-havryshko/sexual-violence-women-ato-upa

[38] Військові жорстоко зґвалтували свою колегу на Львівщині // 24tv.ua/viyskovi_zhorstoko_zvaltuvali_svoyu_kolegu_na_lvivshhini_n689258

[39] Секс-скандал у Збройних Силах: про домагання полковника заявили вже вісім жінок // tsn.ua/ukrayina/seks-skandal-u-zbroynih-silah-leytenant-zvinuvatila-komandira-chastini-v-domagannyah-1288482.html

[40] Замість тюрми — підвищення: секс-скандал у ЗСУ набирає нових обертів // www.rbc.ua/ukr/styler/tyurmy-povyshenie-seks-skandal-vsu-nabiraet-1563969835.html

[41] Жінки-переселенки більш соціально незахищені та дискриміновані, ніж чоловіки — дослідження // humanrights.org.ua/material/zhinkipereselenki_bilsh_socialno_nezahishheni_ta_diskriminovani_nizh_choloviki__doslidzhennjia

[42] ООН: ґвалтування в зоні АТО залишається безкарним // www.dw.com/uk/оон-ґвалтування-в-зоні-ато-залишається-безкарним/a-37605097

[43] Корба, Галина. У ліжку з війною. Зона АТО стала епіцентром розповсюдження проституції // nv.ua/ukr/publications/zona-ato-stala-epitsentrom-poshirennja-prostitutsiji-82840.html

[44] Національний план дій з виконання резолюції Ради Безпеки ООН 1325 «Жінки, мир, безпека» на період до 2020 року // zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/113-2016-р

[45] Wallensteen, Peter. Quality Peace: Peacebuilding, Victory, and World Order. — Oxford, 2015.