Disclaimer. This article was originally published in 2019, before Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine. Some of the issues described in the article have changed. The key change concerns the adoption of the Strategy for the Implementation of Gender Equality in Education until 2030, approved by the Cabinet of Ministers on December 20, 2022. The strategy lays the foundation for comprehensive implementation of the principles of gender equality and non-discrimination at all levels of education.

Introduction

Is it not an exaggeration to state that education has a definitive role in ensuring gender equality? Of course, there are many components of a gender-balanced society, but education in particular is one of the crucial fields.

If our goal is to change gender stereotypes and prejudices that negatively affect both men and women, education professionals’ awareness of gender issues and their ability to reflect on their own prejudices and the gender patterns of the educational system is important. First, quality education is a key to the economic independence of women. Second, primary, secondary, and tertiary education are all socialization environments, i.e., the main places where societal norms and values are created and disseminated.

I will base my analysis on Michael Kimmel’s definition of education as a gendered field of social life and a kind of “factory” of meanings. Starting from kindergarten, education installs an understanding of what it means to be a boy and a girl, a man and a woman. The process continues in schools and universities.[1]

Access to all stages of education for boys and girls, men and women is equal today, but let us not forget it was not always this way. Currently, there are even more female students than male ones in higher levels of tertiary education (masters and PhDs). However, the following problems remain:

Non-discriminatory and gender equality provisions in education are scattered across many documents.

Vertical and horizontal segregation: there are fewer women in the highest managerial and academic positions, university presidents, and academicians at The National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine; and there is still an informal separation of “female” and “male” areas in education and science.

Lack of non-discriminatory policies in education, like strategies to prevent harassment or sexist language.

Educators, parents, and students usually shape the settings of educational institutions, and often re-create gender stereotypes and traditional perceptions of men and women in society without proper criticism.

Therefore, the ‘sex-role’ approach in education is a traditional system of views on the purpose of men and women in society according to their biological characteristics; bringing up boys and girls with a view of traditional (gender stereotypical) norms and requirements imposed by society on men and women.

In contrast, a gender approach to education (or gender-sensitive or gender-responsive approach to teaching) aims to create equal opportunities for the self-realization of male and female students, as well as for non-binary people, focusing on their features and needs for self-realization, irrespective of gender stereotypes and the traditional perception of women’s and men’s roles within society.

The ‘sex-role’ approach entrenches inequalities between the sexes, while the gender approach pursues gender equality instead. The easiest way to understand the difference between the approaches is to look at work training (when students learn the basics of some profession): with the ‘sex-role’ approach, girls bake and embroider, while boys work on lathes. Going beyond the stereotypical behavior would be disapproved. With the gender approach, boys and girls study together in the same program, or children are able to freely choose what to do and the non-stereotypical choices (like a boy interested in cooking) would be appropriate.

In this article, I use the terms “gender pedagogics” and “gender education.”

Gender pedagogics as a type of pedagogy provides methodologies and methods for using a gender approach to education and upbringing, including through the professional training of the educator community on using the approach.

Gender education is the focused teaching of theoretical knowledge and forming practical skills in gender issues. This means specific courses and modules focused on gender, such as “Gender pedagogics”, “Gender sociology”, “Culture of gender equality”, separate educational programs in the area of gender (i.e., master’s degree in gender studies), etc.

One more basic term in the article is “hidden curriculum”, which is the basic, formally assigned function of educational institutions that is reflected in normative documents. Simultaneously, a kindergarten, school, and university shape a certain worldview through the system of unwritten, informal rules and values that are conveyed in the educational environment and teaching. It is like a “shadow side of education” that concerns:The content of classes;

- Organization of educational facilities (school space, teaching, division of positions, school rules);

- Teachers’ style of communicating, etc.

“It [the hidden curriculum] virtuously tries to convince us that two sexes exist, which are ultimately different, almost like opposing biological species, that therefore take radically different positions within the society (with masculine dominating), and that is the natural order of things,”

says Oleg Maruschenko[2].

“The hidden curriculum” permeates all formal rules and informal practices in the educational process from kindergarten to university. School events like “Miss School” and “Mister School” pageants, scouting competitions, clothing rules for children, teaching aids, separate vocational lessons, school books and manuals – these all are gendered. Thus, with the help of the educational system, the gender status quo is replicated, where women and men are assigned different social roles.

More details are provided in Oleh Marushchenko’s article, “Gender shellshock.”

It would not be hard to guess that currently “the hidden curriculum” mainly conveys an obsolete sex-role approach based on gender stereotypes at all educational stages from kindergarten to school. The active community has been trying for a long time to replace it with a gender approach, which is aimed at fully realizing one’s talents and interests without connection to their sex. The first aggravates and reinforces differences and inequalities between sexes, while the second strives for gender equality.

My article attempts to encompass and overview gender changes in the Ukrainian education system since our independence. I mean both formal legislation changes and educational discourses and practices: the traditions of sex-role education and their post-soviet continuity, methodological contradictions, and achievements and challenges of the emerging gender approach in education before, and especially after, 2014.

I did not endeavor to equally cover all stages of education (from pre-school to university) for two reasons: first, such a project would be impossible in an article; and second, the influence of different stages of education on the formation of a personality varies and changes as these stages are not synchronized. For example, at the time of writing this article, there were institutional shifts taking place in secondary and tertiary education, while these processes had just started in pre-school education as individual separate initiatives.

In the article, I mainly focus on gender aspects of Ukrainian education and changes of an institutional nature. Hence, the personal contributions of many researchers, educators, faculties, departments, collectives, and initiative groups working to promote gender education and awareness at schools and universities remained beyond my attention.

I collected comments from Olena Masalitina, an advisor to the Ukrainian minister of education on gender equality and non-discrimination in education and a vice-chair of the EdCamp board in Ukraine; Oleh Maruschenko, a sociologist, director of the Krona gender information and analytics center (GIAC), and author and researcher of gendered education; Yulia Savelieva, coordinator of the all-Ukrainian network of gendered education; and Svitlana Babenko, a sociologist and academic director of the gender studies master’s program at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv.

1. Both Soviet and post-Soviet education turned kids into boys and girls

Let us recall that the sex-role approach in education is a traditional system of views on men’s and women’s roles in society, raising boys and girls relying on traditional (gender stereotypical) norms and expectations from women and men.

This approach prevailed throughout the Soviet era (both formally and informally) and still remains widespread in educational practices, despite significant institutional shifts towards integrating gender equality principles in education after 2005, primarily due to the adoption of the Law of Ukraine “On Ensuring Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men.” A preliminary conclusion can be drawn that the sex-role approach is a legacy of the Soviet education system, which only changed its ideological color since independence.

1.1 Sex-role education in Soviet schools

The controversial Soviet policy of women’s emancipation was promoted by education. On the one hand, this policy aimed to actively involve women in professional employment, but on the other hand, it did not in any way encourage the equal redistribution of roles in the private sphere. Thus, for most of Soviet history (until perestroika), women were simultaneously expected to work hard at the workplace and to take on family and household responsibilities alone.

From 1943 to 1954, Soviet schools practiced (as an experiment) separate education for boys and girls. The first segregated classes were formed during WWII in the territories liberated from the occupiers in 1943, and then in other cities of Ukraine (the ideas of separate education had circulated even before the war).

The following reasons were cited in favor of this approach:

- The educational difficulties experienced by students of different sexes in co-educational schools;

- The need to socialize boys and girls in accordance with their sex (taking into account the nuances of the physical development of different-sex students, preparing them for work appropriate for their sex, practical activities, and military service);

- Ensuring the necessary discipline of students [3].

Boys’ education included intensive military and physical training, while girls’ education was also militarized, instilling in them qualities and skills demanded by certain military sectors (medical facilities, air and chemical defense, army and rear services, etc.). In addition to the different curricula, there were recommendations for teachers on the style of pedagogical communication. For example, for female schools, it was recommended to influence emotions, evoke strong feelings in girls during literature and history lessons, such as protest and condemnation (of anti-heroes), and create situations that would ensure the repetition of emotions[4].

This reform was experimental, and the majority of schools were co-educational. By the end of the experiment, 10-12% of schools were segregated, depending on the stage of secondary education. The main obstacle to the massive introduction of separate education was financing male and female schools, which needed separate classrooms, military training, sports and laboratory equipment, as well as a lack of teachers. The conditions for operating segregated institutions were sometimes unsatisfactory, especially in small towns, and elementary and rural schools remained co-educational[5]. Despite the formal abolition of sex segregation in education in 1954, the sex-role approach in the school system continued to exist.

In 1968, the USSR introduced basic military training for boys and girls in senior secondary education. Students learned how to handle weapons, mastered shooting (my school had a specially-equipped shooting range in the basement), and the basics of chemical defense. For girls, however, demands were lenient; they mainly received medical training.

Those who studied at a Soviet school in the 1960s and 1980s have similar gendered memories of it. I was in school on the eve of perestroika, in 1984, and I still had to be a class commander at a school event called “smotr stroya i pesni” (a review of the formation and songs): I was given a real military cap, commanded the class, and reported to the guests and a military discipline teacher. I also remember the militarized games that were popular at the time in middle and high school (Russian: “Zarnitsa”),” in which girls were assigned the role of medics, although the bravest ones asked for permission to shoot from a machine gun.

While military training covered both boys and girls (albeit with different focuses), labor lessons from grades 5 to 8 were separate: girls sewed, knitted, and cooked, while boys worked on machines. A compulsory home economics course for girls was introduced in Soviet schools in 1960; before that, it was an optional course for older schoolgirls.

From my school childhood, I remember vocational lessons: we wove simple ornaments; made patterns; sewed aprons, scarves, and shorts on old sewing machines; and cooked simple dishes (and then served them to boys). Sometimes boys and girls swapped activities, but teaching practices were different. For example, in our school, girls in the “boys classes” burned pictures on wooden boards, but we were not allowed to use the lathe. Obviously, these practices differed because they depended mainly on teachers’ initiative.

Sex-role education in Soviet schools also extended to students’ outfits. School uniforms were clearly gendered: a dress with an apron for girls in elementary school (later a blue skirt suit became an option) and a suit for boys. The uniform did not allow pants for girls, so in the cold season they had to wear warm leggings under their skirts. The uniforms were the same, so the girls and their mothers tried to diversify them by choosing an exquisite apron (I had a guipure one), buying or making beautiful patch cuffs and collars, which were changed and washed once a week.

Students’ appearance was also subject to discipline: girls were not allowed to walk around “disheveled,” wear jewelry, use cosmetics, or have manicures; and boys with long hair could be sent to get their hair cut (this practice spread mainly in the wake of Beatlemania in the 1960s, when long hair was perceived as an insidious influence of Western culture on Soviet youth).

After the collapse of the USSR and the socio-economic crisis in the early 1990s, school uniforms gradually began to disappear due to a lack of funds to produce them. It was a time of traumatic transition to the liberalization of students’ appearance. Teachers clung to the old ways, and in 1993, I was even publicly shamed in front of the class for wearing a knee-length denim skirt.

Thus, the content and informal practices of teaching and disciplining students in Soviet schools were a logical continuation of the state ideology of forming “proper” citizens, as the state understood them, and included sex-role norms.

1.2 Sex-role approach in primary, secondary, and tertiary education in the 1990s and 2000s

At the beginning of the Ukrainian independence era, the traditional sex-role approach to education was preserved. In 1999, academia developed the first state standard of preschool education[6], the so-called Basic Component of Preschool Education. Although the commentary to this document declared a focus on a fundamentally new, person-centered and humanistic approach to preschool education, the standard contained clear guidelines for sex-role education.[7] In particular, the list of competencies for children to form in kindergartens states that a child “follows a certain social role in relation to sex: a woman is a housewife, mother, wife; a man is a protector, family support, etc. The child should understand that sex, to some extent, determines interests and professional preferences.”

The commentary to the basic component contains an array of gender stereotypes:

“Boys’ brains are more asymmetrical than girls’. The former are dominated by the left hemisphere, and the latter by the right hemisphere. This means that boys’ feelings are intellectualized, while girls’ thoughts are emotionally colored. Boys are more mobile than girls, explore a much bigger life space, have a better manifested search activity, focus on discovering new things, and are more inclined towards risky behavior. Girls’ behavior is aimed at the expediency of survival, preserving the acquired... When answering, a boy looks to the side, at the table, but if he knows, he answers confidently. A girl looks into the teacher’s face, seeking confirmation of her responses... Boys are guided by an idea, but are less demanding about the quality, thoroughness, and visual presentation of the result. Girls are better at performing tasks they are familiar with; they have high performance discipline. Boys excel at spatial and visual tasks, girls at speech tasks. Representatives of the stronger sex react briefly, vividly, and selectively to emotional stimulation, quickly relieve emotional tension by switching to productive activities: they shall not be chastised for a long time by amplifying emotions, the result will be the opposite of what is expected. A girl reacts actively to everything; emotions engulf her brain as a whole.”[8]

The continuity of the sex-role approach in education is gaining new meaning in the context of nation-building. The cornerstone of this process is the discussion around turning back to traditions and the myth of women’s traditionally high position, rooted in the image of the “Berehynia” (guarding mother, literally translated as someone who takes care of).

Oksana Kis in her brilliant essay “Whom does Berehynia protect, or Matriarchy as a Man’s Invention” uncovers how the image of Berehynia is constructed and analyzes its gradual legitimization:

“In fact, the image of Berehynia is gradually turning from an inherent part of a Ukrainian national mythologem into one of the central elements of official state ideology. This process culminated when the Independence Monument was erected on the country’s main square. The young Ukrainian nation (like most European nations at the time of their birth) imagines itself as a young woman in national costume. Raised almost to the heavens (the phallic symbolism of the monument itself requires a separate discussion), she not only embodies the Independent Ukrainian Nation (symbolized by the viburnum branch in her hands), but also unambiguously reproduces, as former President Kuchma said, “the image of Oranta, the guardian of our Ukrainian ancestry,” which is “the essence of our national idea.” At the opening ceremony, government officials repeatedly referred to the sculpture as Mother Berehynia and Mother Ukraine, and the overarching motif of the songs that were played was the idea of Ukrainian children’s devotion to their motherland, Ukraine.”

Gradually, the national narrative started shaping the content of education in institutions, a trend that continues today. Since the late 1990s and early 2000s, primary and secondary educational institutions have been actively embracing the idea of the traditional roles of “Cossacks” (boys) and “Berehynas”(girls) in the context of national and patriotic education. This process was an outcome of the institutionalization of national-patriotic education since the late 1990s in connection with the adoption of the State National Program “Education” (1993), the First National Program of Patriotic Education of Citizens (1999), the National Program for the Revival of the Ukrainian Cossack Culture (2001), the Verkhovna Rada Resolution on the Protection of the National Interests of the State in the Fields of Nationally Aware and Patriotic Education of the Young Generation (2003), the Concept of National-Patriotic Education of Youth (2009), and other documents.

A new branch of pedagogical sciences, “Ukrainian ethnical pedagogy”, and its component, “Cossack pedagogy”, are being developed and institutionalized. They legitimized the new gendered content of education, rooted in national traditions, and set the methodological and teaching framework for educational content.

Here is a recent description of Cossack pedagogy from a 2018 source:

“Cossack pedagogy is a part of folk pedagogy in its apex form, which formed in young people filial loyalty to the native land, the Motherland, independent Ukraine. This is folk educational wisdom, which aimed to form a Cossack knight, a courageous citizen with a pronounced Ukrainian national consciousness and self-awareness in the family, school, and public life.”[9]

Despite the militarization of Cossack pedagogy, its supporters are trying to artificially connect girls and women to the heroic discourse of the Cossacks, relying on the myth of the special status of women in traditional Ukraine:

“The Ukrainian Cossack woman played a huge role in the Cossack survival of the nation, in the grand historical process of the Ukrainian people creating material, moral, and spiritual values. In Cossack Ukraine, women were equal to men, even legally. A man went to Sich, to war, while a woman, the keeper of the family, cared for the household and children, and preserved the family in times of trouble. She was an example for her children in every aspect. Mercy for the poor and disadvantaged, kindness and cordiality were inherent in Ukrainian Cossack women. Ukrainian women were deeply religious Christians, and they raised their children on the moral foundations of the Orthodox religion. The profound education of Ukrainian women amazed foreigners. A Cossack-mother understood best the interests of Ukraine. Women took part in various spheres of life, acting in education, public life, and even governance. In the years of the struggle for Ukraine’s freedom and independence, women joined the Cossack ranks alongside men,” reads the cited collection on Cossack pedagogy.[10]

Thus, as part of national-patriotic education programs, new role models were suggested for children and students: educational institutions starting from kindergartens, schools, lyceums, and up to universities had a ritual of initiating boys into Cossacks and girls into Berehynias.

Girls were involved in militarized activities related to the Cossacks and were assigned clear gender roles. For example, one of the organizers of the “Cossack games” said, “Mostly boys participate because it is Cossack games. However, each team has a Berehynia. A Berehynia is someone who waits for her husband, her beloved, to return home. She raised children, kept the household… but the boys can prove themselves to be real Cossacks: courageous, clever, and smart.”[11]

In the context of national and patriotic education, preschool children were offered different educational programs for boys and for girls, such as “Cossacklings” and “Little fairies” classes in one of the kindergartens in Slavuta. The program for girls read, “Our ancestors called a woman, who creates new life, nurtures and strengthens it, a beautiful and tender word, ‘berehynia.’ This word accurately reflects her divine purpose, her first and foremost essence. We strive to turn girls into real women, who protect and maintain the household, are a kind of cover for the whole family circle, are famous for being neat, outstanding singers, extraordinarily beautiful, and with a high sense of dignity.”[12]

Labor lessons remained the bastion of the sex-role approach in education. The norms on separate education for girls and boys in labor classes were canceled in 2017, but in practice, segregated classes are still held. Olena Masalitina notes that segregation in labor lessons is not defined in any official document, while the current labor lesson curriculum suggests only a set of training modules. However, no documents advise against segregation either. Therefore, the practice of separating classes into groups by sex remains in place in labor lessons, probably due to general inertia and the gender stereotypes of teachers and parents.

A number of surveys of kindergarten caregivers[13] and teachers[14] conducted in 2010-2014 showed the persistence of these stereotypes.

The above examples illustrate how the sex-role approach in preschool and secondary school was incorporated in curricula, methodologies, established teaching practices (labor training lessons), and extracurricular activities (school clubs and holidays). Gender stereotypes also permeate the rest of the “hidden curricula”: the content and illustrations of textbooks, school visuals, how teachers speak, and their attitudes toward students. I would like to provide some testimonies from the collection “Gender-related School Stories” (author’s team, Oleh Marushchenko, Olga Plakhotnik, 2012).

Gender norming of students’ appearance:

“Taking advantage of the fact that I was away on a business trip and my grandmother was taking my child to school, the teacher advised her to cut the child’s hair on the pretext that otherwise it would be necessary to explain to the principal why the boy was wearing a girlish hairstyle. So, the child’s hair was cut. But as a result, he was resentful of the whole world, both because his tastes were not accepted and that his hair was cut against his will.

“When we later had a conversation with the vice principal, she said that they constantly had problems with mine and my son’s discipline because we did not respect the lyceum’s rules, in particular because of the long hair, which they had to fight for several months. Then I tried to get to the bottom of it. It turned out that the problem was not neatness, because his hair was clean and freshly cut, but the fact that it made him look like a girl, and this is not normal.” (p. 10)

School visuals

In school visuals, boys are portrayed as bullies and as saviors (p. 27); in many cases, a human in general in texts is depicted as a man. (p. 39)

Gender limitations of tastes and self-realization:

“The music teacher addresses the class:

- So, I need five kids to play the roles of bandits.

Olenka (she):

- Hey, me, I want to be a bandit!

Music teacher:

- Yikes! Only boys can play bandits. Girls are always dandy and obedient. You will be a snowflake.” (p. 18)

“There was an algebra and geometrics teacher in our lyceum. Her lessons were interesting, she was a kind and amiable person. However, sometimes, when she was in an especially benevolent mood, she squinted and said, “Girls, you should always remember: no matter what you do, the most important thing is to marry well.” (p. 59)

“But the real discrimination began in the 9th grade, when we had to choose a specialization for high school. Almost everyone in our class chose law and history, but that year, there were many applicants from other classes. No one wanted to go to the humanities class, it was considered to be for weaklings, female weaklings in particular. And one day, the teachers decided that everyone except those from our class would transfer to the law and history class, while everyone from our class would go to the humanities class. It turned out that we were enrolled in the humanities only because we were already a fairly established women’s group.” (p. 78)

In higher education, which is aimed at acquiring professional knowledge and skills, the sex-role approach appeared mainly through the “hidden curriculum” – educational and entertainment activities, sexist statements by teachers, etc. The jokes about a woman programmer or physicist who is like a “guinea pig that is neither a pig nor comes from guinea” have been told for years in technical universities. At the same time, girls in engineering, architecture, and diplomacy programs were often told that there was no point in teaching them seriously, because they had joined the faculties only to marry well. The portraits of prominent scientists that adorn school and university buildings aggravate the sexist vibe of the institutions, as there are very few women among them to be role models for female students.

Important issues such as the ability to combine studying with giving birth and raising children, child-friendly learning environments, or combating sexual harassment have hardly been discussed in Ukrainian universities.

For a long time, the presence of gender stereotypes in education and even in scientific work did not cause a critical resonance in Ukrainian society. The case of Rostyslav Bilobryvka, Doctor of Medicine, Professor, Head of the Department of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Sexology at Danylo Halytskyi Lviv National Medical University, is illustrative. For the international conference “Consciousness, Brain, Language,” the scientist prepared theses that included the following:

“A woman does not discover anything, only a man always does. A woman is always waiting to be discovered, because she is a mystery, so how can a mystery reveal a mystery?”; “She does not need it by nature. And to open, to penetrate something is a purely male thing. After all, a man’s entire life revolves around penetrating something, into something. It can be argued that a man’s brain, his psyche, and his physiology are designed to penetrate.”; “A man forgives and forgets, while a woman forgives but does not forget. This quality makes women similar to cats.”[15]

Only in 2018 did such anti-scientific absurdity attract public attention (the Ministry of Health recommended that the university reconsider the author’s suitability for the position he holds, but the university did not heed the advice). One can only guess how many similar “scientific” statements were published in Ukrainian journals and conference abstracts in 1990-2000.

Special attention should be paid to the celebration of gendered holidays, such as “Women’s Day” on March 8 and “Men’s Day” on February 23, which are a vivid example of the sex-role approach in Soviet-era education (and not only in education, as the tradition of congratulating men and women on their “days” was also preserved in work communities). In independent Ukraine, the celebration of these dates has transformed: new, feminist connotations have emerged on March 8, and the Defender of the Motherland Day on February 23 was canceled and replaced by the Defender of Ukraine Day on October 14. In 2022, the name of the anniversary was amended to reflect both men and women and commemorate women serving in the military: “Men-defenders and women-defenders of Ukraine Day” (Den’ zakhysnyka i zakhysnytsi). The present discussions around these holidays demonstrate the level of emancipation in Ukrainian society, and the way they are celebrated in kindergartens, schools, and universities marks well which of the approaches prevails in that institution: sex-role or gender-based.

To conclude this section, I invite readers to recall their own gendered educational stories and analyze their children’s education.

2. Methodological maze of gender pedagogy and gender approach in education in Ukraine

Methodological developments on gender pedagogy and gender approach in education appeared in Ukraine in the early 2000s. The first works were often characterized by methodological confusion: the “gender approach in education” either replaced the sex-role approach in concept, but not in meaning and methodology, or the authors often used these terms as synonyms. Some authors viewed (and still do) sexuality education and preparing for family life as part of gender pedagogy.

For example, in 2004, the Ministry of Education and Science (MES) held a competition to develop gender courses and programs, the best of which were published in the “Curriculum Anthology on Gender Development.” One of the winning programs, “Theory and Practice of Implementing a Gender Approach in Preschool Pedagogy,” constantly suffered from the substitution of the notions of “gender” and “sex-role” education, and closer to the end of the program, the proportion of sex-role education reached the point of guidelines such as, “When forming the elementary mathematical concepts in children, it is desirable to differentiate tasks for boys and girls,” with girls being asked to count dolls and boys to count cars.[16]

The first textbook “Gender Pedagogy” (by Volodymyr Kravets, 2003)[17] also contains such contradictions. On the one hand, the author rightly argues that “traditional sex-role socialization of girls and boys, in which the school is actively involved, continues to reproduce patriarchal stereotypes of interaction between the sexes in public and private spheres. These stereotypes increasingly conflict with the real transformations of gender relations in modern Ukrainian society, hindering expression of individuals, gender equality, and the sustainable development of democratic relations” (pp. 6-7).

On the other hand, the author presents his view on the model of an “ideal wife” – “a woman must be a Woman, before everything. She must be well-groomed and take proper care of herself, even if difficult, because it is not French cosmetics that are needed, but self-discipline” – and gives some advice on harmonizing family relations, such as “a woman should never do her make-up when [her] husband is around, go to bed with one’s face smeared with cream to please others the next day, and not one’s husband.” Or the advice to wives to look like a different woman for their husbands every day: the author recommends that women “change their clothes, hairstyle, jewelry, or their image in general”, “wear the clothes that their husbands like”, “‘bribe’ with a delicious dinner”, “sometimes behave helplessly in household chores” (pp. 215-216).

The author reserved some advice for men also: “A man should be able to make decisions, take responsibility, properly head a household, have a normal appearance: be neat, fashionable, shave every evening; he should be a gallant gentleman, give compliments and care for his wife in a beautiful way: praise her dress and hairstyle; talk to her more often, take her out “in public”, invite her to the first dance (and most of them) at parties; organize leisure together ... predict [his] wife’s desires; provide for her material needs as possible... keep [his] wife entertained; never compare her to others if it is not in her favor; do not be excessively jealous of a wife; treat [his] wife’s whims philosophically, because whim is her natural property” (pp. 214-215).

Unfortunately, this methodological confusion is replicated continuously, as this textbook is cited in 231 sources!

This inconsistency is still repeated in definitions, like in the case of a gender pedagogy defined as “a set of approaches aimed at helping children of different sexes feel comfortable at school, successfully get ready for sex-role behavior (italics by the author) in a family.” At the same time, the goal of gender pedagogy is properly formulated as correcting “the influence of gender stereotypes towards promotion of expression and development of personal traits.”[18]

On the one hand, the author of the cited textbook rather correctly writes that the gender approach in pedagogy and education is an individual approach to the expression of a child’s identity, which gives a person more freedom of choice and self-realization, and helps to be flexible enough. On the other hand, it reproduces elements of the sex-role approach without adequate critique: “Gender education is connected with moral, physical, aesthetic, mental, and labor education. For example, labor education fosters children to realize that the labor of different sexes has different features related to physiological characteristics and the historical aspect of human development: men’s work traditionally involved harder physical activity than women’s work. The connection of gender education with physical education is similar: in physical training classes, exercises that develop various physical qualities and form a certain behavior style are selected (body shape, posture, gait, movement dynamics).”[19] Or: “Our research has shown that toys and games help girls practice activities related to preparing for motherhood and housekeeping, develop communication and cooperation skills.”[20]

In her brilliant essay “The Incredible Adventures of Gender Theory in Ukraine,” Olha Plakhotnyk critically analyzes the formation of gender education at universities in the 2000s. The author rightly questions the methodological content of the “gender” courses and methodological developments of that time.

“I had the opportunity to see the report of Kharkiv universities for the 2008-2009 study year, where the list of introduced curricula on gender included, for example, courses and course modules with extremely eloquent titles: “Spiritual Health (Health Monitoring)”, “Fundamentals of Sexology and Sex Pathology”, “Conflictology (Sex Differences)”, “Chinese Language: Peculiarities of Using the Graphemes ‘Woman’ and ‘Man, Human’” (sic! in the course of hieroglyphics), and even “Latin American Ballroom Dance and Teaching Methods.”

Since the mid-2000s, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Equal Opportunities Program has been an important agent of change in the development of gender education and gender mainstreaming in education, supporting the publication of the first (though methodologically imperfect) interdisciplinary textbook, Fundamentals of Gender Theory, in 2004. In September 2007, the program, in cooperation with the MES and the Ministry of Family, Youth, and Sports, proposed a Gender Awareness Lesson for students at all levels of secondary education, and MES Order #839 of September 10, 2009, mandated holding such lessons annually. In 2010-2011, as part of the program, the first comprehensive collection “Gender Standards of Modern Education: A Collection of Recommendations” was published with financial support from the European Union, covering all levels of education.

In the new millennium, the first departments and centers for gender education and gender pedagogy were established at universities. Back in 2002, the Center for Gender Education, headed by Oksana Kikinedzhi, opened at Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University (the center was renamed the Research Center for Gender Education and Upbringing of Pupils and Students of the National Academy of Pedagogical Sciences of Ukraine in 2008). The first strong moves towards developing gender pedagogy and gender approach in education were also made under the leadership of Tetiana Doronina at Kryvyi Rih State Pedagogical University.

The active work of the KRONA Gender Information and Analytical Center, which has focused on educational projects and training programs for women activists since 2000, was a landmark. The KRONA platform is the first educational project designed for the public, as it was the first time that experts began to go beyond the academic community and work with the general public. Since 2010, KRONA’s main target audiences have been educators and journalists. For the former, KRONA developed the three-level gender training program “Gender Vacation”, and for the latter, a two-level online gender education program. In addition to publishing thematic gender magazines “I”, KRONA is known for its methodological manuals for educators “Gender School Stories” (Oleh Marushchenko and Olha Plakhotnyk, 2012) and “In Search of Gender Education” (a team of authors, edited by Olha Andrusyk and Oleh Marushchenko, 2013), which have no equivalents in Ukraine. The success of this manual exceeded the expectations of the team of authors: it was downloaded more than 170,000 times from the KRONA website (www.krona.org.ua)!

Thus, in the 1990s, Ukrainian education at all levels was dominated by the sex-role approach. Compared to the Soviet period, only the ideological content changed: communist ideals were replaced with the national portrayals of Cossacks and Berehynias.

The development of academic gender studies in Ukraine became the basis for forming a gender approach in education. When analyzing the history of academic feminism in Ukraine, Oksana Kis calls 1991-1994 a period of catching up, when researchers first learned about gender optics in the humanities, and the next stage (1995-1999) was a time of accumulating strength and the initial institutionalization of women and gender studies. At that time, a number of independent gender studies centers were founded (Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, Lviv), several all-Ukrainian scientific conferences were held, and the first translations of the classics of feminist thought were published. The years 2000-2005 were a time of self-confirmation and consolidation of gender studies. In many ways, 2006 was a turning point, when the Law of Ukraine “On Ensuring Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men in Ukraine’’ came into force and the “State Program for Promoting Gender Equality in Ukrainian Society for the Period up to 2010” was adopted. These legal acts contained the principles that establish state support for gender studies. Thus, in the 2010s, according to the historian, Ukrainian gender studies entered a period of maturity and legitimization.[21]

In the early 2000s, in parallel with the development of academic gender studies, the first methodological developments in gender pedagogy and gender approach in education appeared. At that time, this discussion was just starting in the context of the dominance of the sex-role approach, which no one questioned before. Academic gender studies were in their infancy, so the first works often suffered from methodological inconsistency and differences in the interpretation of the gender approach in education, which persists to this day. At the same time, some initiative groups, researchers, and scholars who have devoted decades of dedicated work to developing and popularizing the gender approach in education started their work. Among them were Oksana Kikinedzhi, Tamara Hovorun, Tetiana Doronina, Olena Semikolenova, Svitlana Vykhor, Tetiana Holovanova, Liudmyla Smoliar, Olena Lutsenko, and others. The results of these efforts are described in the next section.

3. Changes in education after Euromaidan: gender (in)equality from kindergartens to universities

Changes in education that were maturating before 2014 received a new impetus after the Euromaidan, both in terms of gender equality and in general, for modernizing pedagogical approaches and practices. These changes pertained mainly to institutional improvements: the start of secondary education reform, enshrinement of anti-discrimination review of school textbooks in legislation, and the start of the first master’s program in gender studies in Ukraine.

3.1 Legal basis for gender equality

Ukraine has intricate legislation on gender equality, including in the field of education. We are referring to the following regulations, many of which were adopted after 2014:

- The Law of Ukraine “On Ensuring Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men” (2005)

- The Law of Ukraine “On Principles of Preventing and Combating Discrimination in Ukraine” (2013)

- The State Social Program for Ensuring Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men until 2021

- National Action Plan for the Implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security until 2020

- Law of Ukraine “On Preventing and Combating Domestic Violence” (2018)

- National Human Rights Strategy (2015) and Action Plan for its implementation until 2020

- National Action Plan for the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Strategy until 2020

The reform of secondary education, the New Ukrainian School (NUS), which is rooted in a competency-based approach, created additional institutional prerequisites for anchoring gender equality in education. According to the NUS concept, social and civic competencies are to be developed in school, meaning all the forms of behavior necessary for effective and constructive participation in public life, in a family, at work; the ability to work with others to achieve results, prevent and resolve conflicts, reach compromises, and respect the law and human rights; and support socio-cultural diversity.[22] Forming these competencies, including respect for human rights and freedoms, intolerance to humiliation of human honor and dignity, physical or psychological abuse, and discrimination on any grounds, is defined as one of the principles of state policy in education in accordance with the Law of Ukraine “On Education” of 2017.

However, the principles of gender equality in education are scattered across different laws. This gap could be filled by the Strategy for the Implementation of Gender Equality in Education “Education: Gender Dimension - 2021”, which has not yet been adopted by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine and which was approved by the Government Committee on Humanitarian and Social Policy in January 2018. The strategy’s purpose is to ensure the comprehensive implementation of gender equality and non-discrimination in the national education system and to identify ways to orient the development of education towards systematic adherence to a gender approach that ensures the national education complies with global democratic principles.

The strategy emerged as a result of the fruitful joint work of the All-Ukrainian Network of Gender Education Centers and the Ministry of Education and Science (MES) with the assistance of Inna Sovsun, First Deputy Minister of Education from 2014 to April 2016. It was with her support that a working group on gender equality and anti-discrimination policy in education and the position of advisor to the MES were created at the MES in 2015. At the time, this idea was supported by Kateryna Levchenko, the government commissioner for gender policy. The working group proposed Tetiana Doronina, Doctor of Pedagogy, Head of the Department of Pedagogy at Kryvyi Rih State Pedagogical University, who had promoted the idea of creating this group, for the position of advisor to the Minister (Serhiy Kvit at that time). However, this position was not established through a decree then, which is why productive cooperation with the ministry did not happen, in part because of the change of government shortly afterward. After forming the new Cabinet of Ministers and appointing Lilia Hrynevych as head of the MES, the position of a pro bono advisor on gender equality and anti-discrimination in education was officially established by a decree, and Olena Masalitina (then Malakhova) became the advisor.

Inna Sovsun Kateryna Levchenko

Tetyana Doronina Olena Masalitina

The support of Larysa Kobelyanska, coordinator of the Public Council on Gender Issues at the NGO Equal Opportunities, and Svitlana Voitsekhovska, MP, co-chair of the NGO Equal Opportunities, head of the Gender Education working group at the Public Council on Gender Issues, enabled a major breakthrough in the discussion and further legitimization of the Strategy for Implementing Gender Equality in Education.

Larysa Kobelianska Svitlana Voytsehovska

“There was strong opposition, particularly from parliamentary groups. It was strange, because very similar strategies, even bolder ones, had been adopted, for example, by the Ministry of Defense, in the training programs of the National Police, but we did not see any opposition from MPs or religious groups. As for the Strategy in Education, a wave of criticism immediately emerged: representatives of religious and pro-religious NGOs and many MPs addressed Lilia Hrynevych. Their main complaint was that the strategy allegedly substituted concepts and actually promoted homosexuality and degradation of the family. Of course, this was not true. However, the MES then withdrew the document for additional analysis and elaboration. A number of lawyers, including some authors of the claims, carried out this additional examination. The text was once again refined, and even the slightest wording about gender equality not present in some other Ukrainian law was removed. But the content of the strategy, aimed at overcoming stereotypes about women and men and achieving equality, remained. After that, the text was submitted to the Cabinet of Ministers again. And at this stage, the process stopped, because the opposition continues, despite the strategy’s clear compliance with the norms of current Ukrainian legislation. Additionally, this is also due to the ongoing reform of the New Ukrainian School, which already causes a lot of unjustified, unfortunately, criticism, and because of political turbulence in general [meaning the pre-election period. – author].”

Liliya Hrynevytch Hanna Novosad

Given the formation of the new Cabinet of Ministers, experts hope that the already finalized text of the strategy will be approved. (As of 2023, a working group to develop the strategy resumed working in summer 2022 and the Cabinet of Ministers approved the strategy in December.)

3.2. Gender stratification in education

Statistics show the feminization of teaching in Ukraine throughout the period of independence, but the number of women and men differs at different tiers of the educational hierarchy and at different levels of education. As of 2017, only 98 men worked as educators and methodologists in preschool education institutions[23], the share of women among school teachers was 85.6%[24], and men make up almost half of the teaching staff of higher education institutions.

The share of women decreases at higher positions: women hold ordinary positions of teachers, lecturers, and educators, while men account for almost 40% of secondary school principals and as much as 90% of higher education institution rectors.[25]

The ratio of women to men in post-graduate and doctoral programs has approached parity. The ratio of women to men in master’s programs in the 2010-2011 academic year was 1.396, and in 2016-2017 it was 1.243. This ratio in doctoral programs changed from 1.478 to 1.099.[26] However, this is not due to an increase in the number of women, but to a decrease in the number of men in science and higher education. The rapid feminization of qualified scientific personnel began in the mid-1990s: between 1995 and 2012, the total number of doctors of science in Ukraine increased by 60%, and of women among them by 190%. For PhDs, these figures were 53% and 137%, respectively. The decline in the number of men with PhDs aged 41-50 is noteworthy.

Researchers Margarita Vorovka and Hanna Petruchenia conclude that the prolonged economic crisis has forced men to look for activities that provide stable and high income. Therefore, the growth in the number of women in the Ukrainian scientific community was and still is due not so much to their active involvement in scientific activities as to the outflow of men from science, as unpromising and unprofitable professional activity. At the same time, feminization is more pronounced at the lower levels of the scientific hierarchy, and the “glass ceiling” still remains at the leadership level.[27]

As we can see, vertical segregation in education still exists (See the diagram. Source: Isakova N. B. Gender parity in science: trends in the world and in Ukraine // Science and science studies. - 2018. - No. 2 (100)

However, the vertical distribution significantly varies among the fields of science where horizontal segregation exists. There are fewer women doctors of sciences in technical sciences (12.4%), physics and mathematics (9.7%), veterinary medicine (7.4%), and transportation sciences (7.1%) than in other fields. More women are pursuing doctoral degrees in traditionally “women” disciplines, such as psychology (60.6%), pedagogy (59.1%), art history (56.3%), sociology (52.6%), geography (50%), physical education and sports (50%), and social sciences (45.2%).[28]

Over the one hundred years (1918-2018) of the existence of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), there was a total of 1,597 NAS members (full members and corresponding members); of them, only 70 were women (2.3%). Over the past hundred years, there has been a negligible “progress” of 0.3%: today there are five women academics among the 193 full members, i.e. 2.6%.[29]

Positive developments include a decrease in the gender pay gap in education. In the second quarter of 2017, the gender pay gap in education was 3.2%[30] compared to 23% on average in the economy. This gap has decreased over time: In 2011, women in education earned 10.2% less than men on average.[31]

3.3. Gender equality for the youngest: preschool education

The content of preschool education in Ukraine is regulated by the Law of Ukraine “On Preschool Education”, the basic component of preschool education (current version 2012), and partial programs that contain recommendations for specific areas of training and education approved by the MES, from mathematics and chess to choreography and English.[32]

The development of a gender approach in preschool education is still controversial. Despite the emergence of the first critical studies on preschool education based on gender methodology, kindergartens still replace gender education with sex-role education.

For example, the portal of Ukrainian educators offers the following interpretation of it: “Gender education is generally defined as an influence on the mental and physical development of boys and girls aimed to optimize their activities in relations between different sexes and the formation of their sex-role position. Under the influence of adults — teachers and parents — a preschool student must acquire a sex role or a model of behavior that allows for the individual to be identified as a woman or a man.”[33]

In 2019, the KRONA expert team began a comprehensive study of the level of integration of gender issues into the preschool education system, which involved various methods and levels of analysis, from preschool programs to observation at kindergartens in Kharkiv and Kharkiv Oblast.

Oleh Marushchenko explains:

“First, we took all the programs recommended by the MES and a few so-called partial programs, such as English, chess, and choreography. The situation should not be generally characterized as catastrophic, because normal and even good programs in terms of non-discrimination in education do exist. After that, we analyzed the information from kindergarten websites, analyzed the representation of women and men in the preschool education system, studied all the popular holiday scenarios we know, visited institutions and analyzed their space. In other words, we used all the aspects of analysis that we knew, which we had previously implemented at school, to analyze kindergartens. As a result, we came to a preliminary conclusion that the problem is mostly not in the scenarios or programs, but primarily in those who implement them… Even a non-stereotypical program can be distorted by the stereotypical worldview of an adult...”

The project will result in a book with research findings and recommendations for parents, teachers, and psychological services.

Thus, after 2014, preschool education generally continues to substitute gender education with sex-role education. However, the first research projects are emerging that could kick-start institutional changes in preschool education, following the example of the path that secondary education is currently taking.

3.4. Secondary education: from experiments to institutional changes

Secondary education in Ukraine is regulated by the Law of Ukraine “On Education”, the Law of Ukraine “On General Secondary Education”, and various guidelines and regulations (resolutions, instructional letters, and provisions). Educational content, such as textbooks, manuals, dictionaries, collections etc., published at public expense, undergoes a complex procedure of examination and approval by the MES.[34]

As I noted, the work of the KRONA Gender Information and Analytical Center, which had been actively cooperating with educators since 2010, was an important link in the transition from theory to practice of educational change. Since 2014, the team has continued its research and training activities. The cover of the KRONA “Gender is coming!” (published in 2018) contains a fascinating and lively story about the experimental work “Scientific and methodological principles of implementing gender approaches in the work of educational institutions.”

The KRONA team implemented this project from November 2014 to June 2018 in eight public schools in Kharkiv Oblast (two of them were in rural areas, two included a kindergarten, and three were innovative type institutions – gymnasiums or lyceums).

In the first stage of the experiment, which lasted for a year and a half, the team trained and consulted with the staff of each educational institution about forming a gender-sensitive worldview and gender analysis of lessons, school textbooks, and school visuals. At the beginning of the experiment, the team faced indifference and sometimes even a cautious attitude from teachers, but after the training phase, the number of teachers who favorably evaluated the ideas increased significantly.

In the second phase of the experiment, KRONA organized an interschool creative gender workshop to develop gender-sensitive school visuals and held a competition of gender pedagogy materials. The last event of the second year of the experiment was a training for participants of the pilot institutions to develop knowledge and skills in anti-discrimination reviews of school textbooks. In the spring of 2016, the first nationwide examination of a set of 8th grade books took place under the auspices of the MES.

During the third year of the project, the Gender Pedagogical Almanac was published, bringing together 30 essays written by teachers from experimental institutions about their experience of overcoming gender stereotypes and discrimination in their practical work. The style of this publication, like all KRONA publications, was “live” and interesting stories where educators shared their experience of changing teaching practices.

“When I started working on the issue of gender, I saw the world with different eyes.”

“I started noticing things that had previously been out of my sight: texts of exercises and tasks, drawings, illustrations, etc.”

“I began to think about why a man is always perceived as superior to a woman...”

“I had conversations with 3rd grade students about how they understand the separate roles of women and men in society. The children are well aware that ‘a man is able to easily cook for himself’ and ‘a woman can replace a blown fuse without much effort.’”

“When submitting a student’s work to the Junior Academy of Sciences, I signed it using feminine names of my profession (in Ukrainian, a word ending distinguishes female and male nouns): ‘Supervisor: teacher. ..’ (kerivnytsia, vchytelka:..). After a while, I received it with corrections [reversed to male endings]: ‘Supervisor: teacher...’ (kerivnyk, vchytel). I was chided and told that it should be written only in this way.”

An important event in 2016 was the beginning of cooperation between two NGOs, KRONA and Edcamp Ukraine, and the MES. A remarkable result of this cooperation is the institutionalization of non-discrimination principles in school textbooks published at public expense.

The first review of all school textbooks submitted to the competition for MES approval was held in 2016. This and subsequent examinations revealed numerous instances of stereotypes and prejudice in texts and illustrations. The examination found that most children do not see in Ukrainian textbooks a reflection of themselves, their families, or the particular circumstances in which they live. Many anachronisms unacceptable for a democratic country, such as the names “Negroes” and “Gypsies” were found and removed from textbooks.[35]

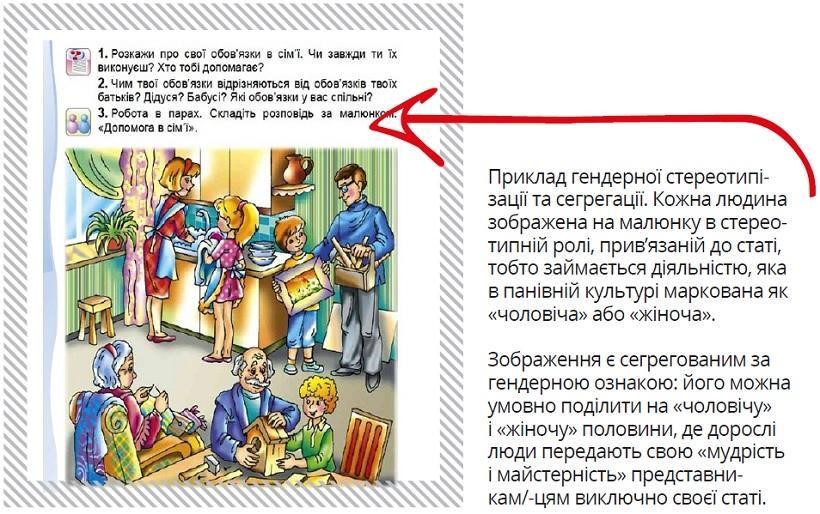

One of the most common stereotypes in school textbooks is gender stereotyping: in the texts of tasks and illustrations, authors portray boys and girls in stereotypical roles, thus promoting outdated forms of behavior. This may include the idea that only girls can take care of children or that only boys can pursue technical professions.

The anti-discrimination expertise methodology and certification program for experts were developed in accordance with the current legislation of Ukraine based on national and international research in this area and UNICEF international reports on cases of discrimination in textbooks around the world. A total of 845 textbooks were examined between 2016 and 2019. Monitoring of how comments were taken into account showed a positive trend: authors and publishers have become much more responsive to recommendations.

Results

of the anti-discrimination review of draft textbooks,

Submitted to the competition for MES approval (2016–2019),

As provided by the working group on gender equality policy and preventing discrimination in education

|

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

|

Number of draft textbooks, grade |

72cp. (8th grade) |

195cp. (9th grade) |

322: 103cp.(1st grade) 30cp. (5th grade) 189cp. (10th grade) |

256 books 91cp. (2nd grade) 21cp. (6th grade) 144cp. (11th grade) |

|

Reflect non-discriminatory approach to education |

0cp. (0%) |

4cp. (2%) |

77cp. (24%) |

108cp. (42%) |

|

Partially reflect non-discriminatory approach to education |

10cp. (14%) |

49cp. (25%) |

221cp. (69%) |

146cp. (57%) |

|

Do not reflect non-discriminatory approach to education |

62cp. (86%) |

142cp. (73%) |

24cp. (7%) |

2cp. (1%) |

The anti-discrimination review allowed increasing the sensibility of textbooks, particularly on gender issues. For example, humans in textbooks used to be portrayed mainly as boys or men. In the new textbooks, authors and illustrators picture different sexes equally.

In the beginning, there were not enough experts who could officially perform the anti-discrimination review. For example, in 2017, the list of experts to perform the content review of 195 authentic layouts of 9th grade textbooks took up 168 pages in the decree, while only 21 people worked on the anti-discrimination review of the same volume.

In 2018-2019, the expert circle expanded significantly:

“We now have 76 certified experts. This number may change because we revoke certificates from time to time. After such serious training, people become experts, but each time their work is analyzed through supervision. If a person performs a review without proper quality, the certificates are revoked and the person cannot participate in the review again,”

explains Olena Masalitina.

In 2018-2020, a communication campaign also saw progress: we managed to explain what the essence of the review was, why it was needed, what mechanism it used, what it was based on, who performed it and why, what training the experts received, etc. According to Masalitina, “The training of publishers and authors of school textbooks supported our communication. During the in-person trainings and constructive dialog, everyone better understood what was being discussed. The participants then communicated with their colleagues, and gradually the tension around the review subsided. As for the MES, we no longer receive so many requests to immediately cancel a review. The UN Population Fund in Ukraine (UNFPA) supported the trainings, and they will continue doing so, as the demand from publishers is only growing.”

Communication is also improving as a result of the expanding expert circle, because it includes employees of educational institutions and government and non-governmental organizations in different parts of Ukraine who form certain centers of gravity in their regions and social circles.

The anti-discrimination review of textbooks is the most successful educational change that has grown from a grass root initiative of a group of authors to an institutionalized mechanism. In 2018, an MES decree approved methodological materials for reviewing drafts of school textbooks. The decree clearly lays out the requirements for textbooks in terms of anti-discrimination content, as enshrined in the Constitution of Ukraine, namely:

- Presence of various characters/actors of different ages, genders, places of residence, etc.;

- Presentation of characters/actors mainly in non-stereotypical social roles (e.g., both girls and women and boys and men are involved in household chores);

- No segregation and polarization based on certain characteristics (e.g., girls and boys are jointly involved in games and activities, and are not opposed in different types of activities);

- Non-discriminatory language is used, i.e., language that is free of androcentrism, sexism, and other discriminatory meanings.

The recommendations are based on the methodological materials of the team of authors, including Tetiana Drozhzhyna, Olena Masalitina (Malakhova), Oleh Marushchenko, Yana Salakhova, Volodymyr Selivanenko and others.

However, the MES does not currently require an anti-discrimination review of other educational content (e.g., visual materials, educational activities, etc.). This review is conducted by researchers’ grass-root initiatives. For example, KRONA developed gender-sensitive visuals for schools.

Overcoming gender discrimination in educational institutions is one of the EdCamp platform’s many areas. This world-famous project for teachers works to improve Ukrainian schools and build a community of responsible teachers.

The anti-discrimination review of textbooks unjustifiably provoked a negative reaction from certain groups in society, which created threats to its further implementation. In her book “Gender Gravity”, the Government Commissioner for Gender Policy Kateryna Levchenko writes that manipulations around gender issues appeared in public discourse in 2010, after Viktor Yanukovych came to power [elected president – Editor], as a means to stop Ukraine’s European integration. They intensified with renewed vigor in 2016, now as a tool of hybrid warfare. Today, the main thesis of anti-gender movements is that “gender is a foreign value that is being imposed on us.”[36]

Anti-gender movements are a transnational phenomenon, and the topic of children is the most fertile ground for opposing the policy of gender equality in education: it is claimed that “gender ideology” has penetrated schools, that students are being “brainwashed” and “indoctrinated with homosexuality.” Parents’ groups were organized to counter these invented threats. One of these groups is the Parents’ Committee of Ukraine, which conducted public activities until the end of 2013 such as organizing protests opposing European integration. In 2010-2013, the organization published several brochures on threats of gender education and juvenile justice. After the Revolution of Dignity, the organization became less visible due to the change in political discourse and the growing public support for European integration.

“Anti-gender” initiatives became active with renewed vigor two to three years after Euromaidan. Other conservative, religious, and pro-religious forces joined them. In June 2018, their attacks focused on the anti-discrimination review of school textbooks. The blog “Homodictatorship. How to Corrupt Children” by Hanna Turchynova, Dean of the Department of Natural and Geographical Education and Ecology at the Drahomanov National Pedagogical University, had over 30,000 views as of June 2019. It reads: “Gender ideology has slowly penetrated our society and reached schools. And if someone associates the word “gender” with equal rights for men and women, they are mistaken. Because the main goal is to overcome heterosexuality and create a new type of person who has the freedom to choose and embody their sexual identity regardless of their biological sex”[37].

Turchynova’s blog posts conflated the concepts of gender and sexual orientation; the criticism of the anti-discrimination review is justified as “devaluing a complete family, fatherhood and motherhood” and “homodictatorship.” The author was referring primarily to the expert conclusion asking to replace the word “parents” with the word “relatives” (“parents” in Ukrainian sounds like the plural of “father”) in the exercises, such as “Together with your parents, make a daily routine list for your family”, “Together with your parents, discuss where you can play.”

As a result of numerous appeals to the MES, the Ministry directed the methodological materials for revision. The expert circle was significantly expanded to include those who had criticized the review. They, in particular Hanna Turchynova, were invited to make suggestions to the methodological recommendations, and all materials were provided, but, according to Olena Masalitina, there was no response to the invitation to work together. The methodological recommendations were eventually finalized by an expanded expert circle, organized as a special working group, whose report No. 1/07/18 of July 15, 2018, was presented and approved at a special expanded meeting of the Working Group on Gender Equality Policy and Combating Discrimination in Education, which took place at the Verkhovna Rada Committee. “These numerous appeals and criticisms have caused a wave of public interest in the review. We gave a lot of interviews and comments. Many people wrote that they finally understood why this review was needed, and reacted positively,” the expert adds.

Thus, in the period after Euromaidan, the secondary education sector was characterized by the convergence of civil society organization initiatives and experts representing institutional structures, primarily the MES. Political will, i.e., the willingness of the MES leadership to cooperate, had an important role in this process.

Against the backdrop of these changes, the persistence of separate education for girls and boys in some public schools is particularly striking. For example, gymnasium No. 9 in Cherkasy offers separate programs for children in primary school: “young ladies” join the course called “School of Young Ladies,” do aesthetic gymnastics, fitness with elements of choreography, etc., and “cadets” study military affairs.[38]

Gender review of textbooks has become an effective advance in secondary education, even though it has attracted many attacks from conservative circles.

The “hidden curriculum” is still waiting for a “reset,” because the changes rely primarily on the immediate participants of the educational process on the ground: teachers, school administrators, regional education departments, and the parent community.

3.5. High school: local initiatives and lack of system thinking

Gender education in universities is the basis for developing a gender approach in education at all levels. Future employees of schools and kindergartens study in pedagogical institutions; the level of gender sensitivity of representatives of all other professions directly depends on whether gender issues were discussed during their studies.

In 2010-2017, many universities established gender education centers or gender studies departments (Kharkiv, Ostroh, Hlukhiv, Chernihiv, Odesa, Kyiv, Khmelnytskyi, Ternopil, Uzhhorod, Zhytomyr, Sumy, Kryvyi Rih, Cherkasy, Zaporizhzhia, and Mariupol). Some of these centers and departments were established with the support of the Program for Equal Opportunities and Women’s Rights in Ukraine as part of a joint project of the EU, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), and the UNDP.

See more about the development of gender studies in the article by Oksana Kis: “Feminism in Ukraine: steps towards yourself. Part 1. Academic feminism”

In 2012, the Kharkiv Regional Gender Resource Center in partnership with the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Ukraine founded the All-Ukrainian Network of Gender Education Centers, taking into account the experience of gender centers, gender education centers, and gender studies departments at universities established with the support of the EU-UNDP Equal Opportunities and Women’s Rights Program in Ukraine.

As of 2019, the network included 30 gender education centers. In 2015, the Gender Resource Center at Sumy State University became the network coordinator. In the same year, a gender audit of 14 universities in 10 regions of Ukraine was carried out as part of the Gender Mainstreaming in Higher Education project, which aimed to promote gender equality and gender-sensitive approaches in Ukrainian universities. However, according to the network members, no administrative decisions were made based on this audit.

In 2015, the academic journal Gender Paradigm of Educational Space was founded at Kryvyi Rih National University, and the Scientific Notes of the National University of Ostroh Academy launched a new series, Gender Studies.

Yulia Savelieva, the network coordinator, admits to a certain decline in the consolidation of the network’s centers:

“Three years ago, the network was at its peak, we were cooperating with international partners, but recently we have experienced a certain decline. The work we do has become less unifying, it is rather separate, each center works in its own way and its own city. We are still holding on to the idea of implementing a gender equality strategy, and we hope that this will happen.”

Tamara Martsenyuk, PhD in Sociology, Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy, and gender expert, also spoke about the lack of a systematic and institutionalized approach in an interview with the Human Rights Information Center:

“Master’s programs are being created at universities at the level of some initiatives and individuals, such as at Taras Shevchenko University. If not for individuals, this program would not have been created. At the Kyiv Mohyla Academy, several departments teach gender studies and courses related to gender issues, but this is also more of an individual initiative. We need the Ministry of Education and Science to work more systematically, because now the MES relies more on the private initiatives of universities, individual teachers, and grant programs.”[39]

A particular challenge to institutionalizing gender studies at universities is also posed by the attitude of society to gender issues in general and the intensification of anti-gender initiatives: “Anti-gender movements are not so innocent, seemingly with no impact on the field of education. At the same time, they are a kind of stimulus, because their current activism clearly provokes more active discussions. And local centers of the movements join these discussions. Not all of them, and not always, but they respond to such things as appeals from city and regional councils to ‘ban gender.’ So this movement is definitely a threat to us, and a kind of stimulant, an irritant. Although we do not have any consolidated position on how to respond to such things,” says Julia Savelieva.

A landmark event for institutionalizing gender education in Ukraine was the start of the first master’s program in gender studies at the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv Department of Sociology. The academic director of the program, Svitlana Babenko, speaks about its features: “First, our work is based on the experience of those who have been developing gender studies in various formats since the 1990s. We literally stand on the shoulders of titans and apply their experience. Secondly, the double degree program is open to the international arena and is built on the basis of parity and mobility: not only do we go to Sweden to gain experience, but Swedish students come to us to gain experience and a diploma. Thirdly, the program is practically oriented, supported by civil society, and we have cooperation agreements with a number of leading sociological services that conduct research on gender issues, with governmental and non-governmental organizations.”

In addition to the developments related to starting gender studies programs and courses at some universities, the first public discussions around gendered and discriminatory communication practices took place, including about sexist statements by teachers and sexual harassment. In 2017, 13 Rivne State University of the Humanities graduates, students, and teachers reported to journalists about harassment by choreography professor Volodymyr Godovsky, who promised to pay for the students’ dormitory, find them jobs, and solve their academic problems in exchange for intimate services.[40]

Volodymyr Godovsky

“If you are my student, I will not need a rector, vice rector, or dean. Because I will have the moral and immoral right to take care of you. You will kiss me hard later. I will pay for your dormitory if you kiss me hard. We will talk later about what kind of relationship we will have. But I will protect you. I like this type of women, girls. And I will support you, you’re cool, just a little bit stiff. I’m going to open you up.”

According to the girls, they did not go to law enforcement agencies because of shame and fear of losing their jobs or being expelled from the university. Although one professor said she had complained to the rector about her colleague’s actions, she was not believed. The professor had been behaving like this for years! The professor resigned only after the facts were publicized nationally.

In the absence of policies to combat discrimination and harassment at universities, it is important to mobilize students to counter these phenomena. The first practices of such public activism in Ukraine appeared two years ago. In 2017, female students publicly demonstrated against sexism and sexual harassment in universities: activists of the FemSolution student initiative wanted to hold a “Say no to violence at the university” rally at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, but their action was disrupted by far-right activists.

Text: Sexism - a first step to further violence

The catalyst for the action was when a professor wrote publicly on Facebook that students teased him at an exam with miniskirts and that he almost gave one of them extra points for each of her seven piercings.