Translated from Ukrainian by Iryna Malishevska.

WHY DO FEMINISTS CRITICISE MILITARISM?

The everyday patriarchal interpretation of war assumes that men fight in a war while women stay at home ‘under their protection’. War is legitimate aggression towards the enemy; and aggression is supposed to be appropriate only for men. It is considered that a woman can protect her children in a dangerous situation (‘like a she-wolf’), but the image of a warrior in culture is purely a male one. Exceptions are so rare that we know these women either by name or as mythical characters, think of Joan of Arc or Nadezhda Durova, the ‘Cavalry Maiden’.

Nadezhda Durova, the first female officer in the Russian Empire

I would like to skip the world history of wars and armies and only point out that men were and are given major roles in military service because of their greater physical strength compared to women. Nevertheless, the history of women warriors is no shorter than the history of warfare itself.

The patriarchal lens prefers to ignore or misrepresent this history. Aristophanes' comedy Lysistrata, written in the fifth century BC, started another tradition of depicting women as peacemakers (according to the comedy plot, women refused to have sex with men until they stopped the war).

Violence against the women of the defeated enemy is a part of war. Of course, the standard feminist position is to criticise and reject war and its companion—militarism. Feminism criticises war as a purely patriarchal phenomenon and the consequence of a masculine struggle for power and territory. In a perfect feminist world, there should be no wars.

The theoretical articles on the subject refer mainly to the chapter of Gender and Nation by Nira Yuval-Davis, in which she briefly and superficially labels women's antiwar initiatives as similar to patriarchal ones while in reality they are not; and presents women in the armed forces as if they think they will be equal to men, when in fact they will not be.

The cover of Gender and Nation by Nira Yuval-Davis

This text is written during the seventh year of the war that the Russian Federation has been waging against Ukraine. The article outlines and analyses the different attitudes to war among Ukrainian feminists. The position ‘war is men's toys, militarism is bad’ is very simplistic and extremely risky in the case of Ukraine, and this text aims to prove that.

WAR AS A FAULT LINE BETWEEN UKRAINIAN AND RUSSIAN FEMINISM

The Russian-Ukrainian war has changed the plight of Ukrainian women. Typical peacetime gender-based problems were multiplied by the gender-based problems caused by the Russian military aggression, such as shelling of houses, curfews, economic problems, and repression. There are many women and girls among the internally displaced people. The specific problems of women during the war have also become a constant Ukrainian reality: women's organisations receive many reports[1] of sexual violence by armed men, and this includes military men of both armies. Domestic violence has been recorded[2] in the families of war veterans and, as a result of long-term stress, they can come undone and turn violent.

Many women entered the Ukrainian army, in particular they took combat positions of both formalised and informal volunteer battalions, and hence participation in hostilities has also become women's business. The ongoing repressions of the Crimean Tatar community in Crimea affect women, although they are mostly directed at men. Wives are responsible for freeing their husbands from imprisonment and supporting their families which often have several children. Thus the war has become a feminist affair and the subject of hot-button and painful feminist discussions.

A heated discussion[3] started on March 4, 2014 in the “feministki” community on the LiveJournal blog platform. At that time, it brought together several thousand participants from Russia, Ukraine and other Russian-speaking countries. The subject of the discussion was Vladimir Putin’s quote who, when referring to the Russian army in Crimea, directly said, “We will stand behind the women and children, not in front, but behind them”. The Russian participants immediately began to explain these words as being poorly formulated. Later, after information about the rape of a Ukrainian girl by militants in the occupied territories, the Russian participants began to shift the conversation to potential similar actions by the Ukrainian army[4] and commented on the petition about the freeing of pilot Nadiya Savchenko that the topic had nothing to do with feminism[5]. Because of the moderators' moderate attitude, the aggressive anti-Ukrainian comments in the community were hidden, so reading the discussions when not in real time does not show how the emotions had run high. Apart from veiled sympathies for the aggressor, from time to time a different, more neutral attitude would appear.

«And it is better not to have any relations or contacts with those who in any way take part in these macho games. Sometimes it happens that an absolute majority of the society begins to participate in these ‘macho games’ in one way or another and then a refusal in principle to participate in anything related to these ‘macho games’ may become a factor which limits chances to be socially active in general»[6].

«What a striking post you wrote. Some of the comments are an excellent illustration (not the first time in this community indeed) that ideology, the politics of one's state and so on are more important than feminism»[7].

(The comments are quoted from different threads in the “feministki” community.)

Let me quote the explicitly imperialist views of public Russian feminist Natalya Bitten:

«In this frame of reference, embodiment of evil is needed. The empire fits just fine in this role. They don’t care about the fact that their republic was being pumped full of resources taken from the Urals, Siberia, and the Far East. The empire owed them till the rest of their lives. Ukraine lived a much better life than Siberia. Thanks to what money?»[8]

Such discussions started a process of polarising Ukrainian and Russian feminists. “Ideology, the politics of one's state and so on” became more important than not just feminism, but a certain nationally neutral and compromising version of feminism that had no internal conflicts or did not consider them significant.

Researcher Tetiana Zhurzhenko wrote back in 2011 that the discourse of ‘national feminism’ prevails in Ukrainian gender studies. It is based on the interconnection of nationalism and feminism in Ukraine. As two marginal ideologies, they need each other and stand in affirmative positions[9]. However, before the war, democratic nationalism was more a matter of academic feminism than of grassroots feminism, so the Russian-based platform in Russian was an acceptable space for discussions of grassroots activists. Over time, statements similar to those quoted above obviously began to bother some Ukrainian feminists.

Such discussions were predicted earlier in 2009 by Russian feminist Madina Tlostanova in her book Gender Epistemologies and Eurasian Borderlands in which she explicitly pointed out that Russian knowledge is constructed as imperial “and its non-Western nature will not save it from its discriminatory attitude towards its own internal and external others”[10].

As soon as ‘others’, Ukrainian pro-Ukrainian feminists, started to somehow articulate not even their own otherness, but their newly discovered interests, they were met with resistance. Indeed, a Ukrainian woman who lived or lives in the occupied territories, who has relatives or immovable property there, or who is afraid that the troops will enter her town, or who suffered or is suffering in some other way, is in a worse situation than a Ukrainian man, a Russian woman and a Russian man. The first category enjoys men’s privileges, while the second and third categories enjoy the privilege of not suffering from war. If the second group’s privileges are not recognised, it is a problem.

It is revealing that it is extremely difficult to find examples of Russian feminists openly condemning the aggression of the Russian Federation. Even if this position manifests, it is mentioned in passing within other topics and is almost never an open statement. Only the position of film critic Maria Kuvshinova is unambiguous and explicit:

«When Cargo 200 came out in 2007, many assumed that the girl chained to a bed by a maniacal policeman was Russia tortured by uniformed sadists. However, the more time passes, the harder it is to ignore that Russia itself is Captain Zhurov, an impotent law enforcement officer with a pale face, while his beloved victim, who receives a dead body as a gift, is someone else, for example, Ukraine»[11].

The position of ‘all-feminist values’ also manifested in internal Ukrainian discussions.

«[...] How dare you put men’s ambitions and militarism over your own interests as a woman. [...] These monkey games over territory are of little interest to me, because they bring me no profit»[12].

— a comment in the Feminism.UA community which is the largest Ukrainian Facebook group on feminism.

A counter-argument of the other party is as follows:

«However, the fact remains that women are safer in peaceful, unoccupied territory than in a war zone, in a territory occupied by troops of another country, or even in a territory where deemed ‘friendlies’ are deployed close to the line of conflict, or in a territory that is being de-occupied. During the war, it is not only deemed foreign men who are a danger to women. During the war, deemed ’friendlies’ also become more dangerous. [...] But all this does not negate the simple fact, the answer to the questions: first, who started the war, and second, who is responsible for the ongoing war»[13].

DIFFICULTY WITH UKRAINIAN NATIONALISM

Some of the feminists got attracted to a non-pacifist version of feminism (and those who previously held this position strengthened their beliefs), so a debate has developed in Ukraine about the compatibility of nationalism and feminism. Olga Plakhotnik and Maria Mayerchyk opposed a ‘linear’ ‘time of the nation’, which implies the concept of progress, to a ‘mixed’ ‘time of feminism’[14].

Read the article by Maria Mayerchyk and Olga Plakhotnik “Between Coloniality and Nationalism: Genealogies of Feminist Activism in Ukraine”.

Nationalism Reframed (1996) by Rogers Brubaker highlights the complexity of understanding post-Soviet nationalism[15]. The author identifies three types of nationalism in post-Soviet territory: ‘nationalising states’, ‘national minorities’, and their ‘external national homelands’. For Ukraine, these are Ukrainian, Crimean Tatar, and Russian nationalism respectively. Brubaker did not explicitly predict war in Ukraine, but noted the implicit conflict between the first and third varieties of nationalism embedded in the very institutional construction of the Soviet Union of ‘national republics’.

This topic is difficult to explore and sensitive for the Ukrainian population. The problem has become even more acute because of the war. Without getting into a detailed analysis of this concept, which has its flaws (for example, it gives the same explanatory scheme on the development of the ‘national question’ in all post-Soviet republics, although the contexts of Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan differ a lot), I would like to point out that this approach is significantly more productive for analysing post-Soviet nationalism than the above-mentioned idea of ‘time of the nation’ as linear progression, which only relates to Western nationalism and only its former forms (we can say the same about the progressiveness of the nation state compared to an absolutist monarchy, because it expands the rights and opportunities for most of its citizens, but this issue was closed in 1789).

When talking about nationalism and the further evaluation of its compatibility with feminism, we need to consider the virtual differences in its perception in the West (what is called the West in Ukraine, in Western literature is called the Global North, and this terminological difference is illustrative in itself) and in Eastern and Central Europe. For example, Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak points to two different and nearly conflicting approaches to how to define this term. Western scholars see nationalism as “an intellectually dispersed movement with an authoritarian or even fascist bias” (I disagree with her and consider this an overgeneralisation), while nationalist groups in Eastern Europe, focused more on a variation of democratic nationalism, “see their patriotic nationalism as something pre-set and are surprised that others are more focused on improprieties of nationalism rather than on its democratic nature”.

Historian Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak

Indeed, the dissident and opposition movements in Central and Eastern Europe in the second half of the twentieth century provide us with numerous examples of the struggle for democratic values. In the notes to this text, the researcher points out, “The dominant culture, with its corresponding mindset, tends to view itself not within a national framework, but within the broad space of a human civilisation”[16]. Such a Western universalisation of the self unifies contexts outside the Western world and seeks (consciously or unconsciously) to adapt everyone to a local norm under the guise of the common. The critical attitude of some Ukrainian feminists towards nationalism reflects a rather Western paradigm and results in an uncritical transfer of it to the local context.

For example, critical attitude to nationalism, presented as a matter of course without explaining the reasons for the criticism, does not answer the question of why national identity cannot be important (and why people choose to consider it important) and how it is so fundamentally different from gender identity, which we recognise as important. Yes, a nation is a social construct, but gender is also a social construct too, however critical feminism does not require people to identify as agendered. Race is also a social construct, but fighters against racism do not require people to identify as raceless either. If one can be ‘proud’ (meaning ‘to recognise and treat with dignity’) of sexual orientation, why cannot one be proud of national identity? In fact, discussing it is very difficult because not only do opposing sides not have consensus on the possibility of democratic and affirmative nationalism, but also on the very meaning of the term.

Let me disagree with Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak and say that in today’s Ukrainian reality the concept of ‘nationalism’ is a definition close to being empty, because it is understood as a very wide spectrum of concepts, from explicitly ultra-right views to pragmatic identification of oneself with a certain territory of residence, “I support nationalist ideas, because I do not want Russian soldiers in Kirza boots to come to my house tomorrow. It's not in my interests at all”[17].

Without a clear definition of how exactly the concept of ‘nationalism’ is defined within a particular discussion, its criticism risks at best being unconvincing, at worst it takes the side of cross-border nationalism of the current aggressor. I totally agree that some manifestations of Ukrainian nationalism are explicitly chauvinistic and that the Ukrainian ‘nationalising state’ as a structure is structurally exclusive, at least in relation to Roma people and partly to Crimean Tatars. However, simplistic positions in the discussions do not help to solve this problem domestically, and even less so at the higher level. While in Ukrainian Crimea Crimean Tatars were a minority whose interests were passively not respected, when Russian aggression started on the mainland, they were exposed to direct repressions. This is the same structure of the situation as quoted in one of the discussions above: for the Ukrainian woman, gender problems of peacetime have been multiplied by wartime problems.

Historically, specific perception of Ukrainian nationalism in Ukraine developed in pre-Soviet and Soviet times: even the Marxist Ukrainian Social Democratic Labour Party was labelled as ‘Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism’, while ‘internationalism’ in practice camouflaged russification (Ivan Dziuba in his famous work Internationalism or Russification gives arguments in its favour from Leninist positions). This fact raises the question of how much criticism of contemporary nationalism differentiates itself from such phenomena as:

- the imperialistic paradigm of Tsarist Russia, where the Ukrainian language should not have existed;

- the left-wing authoritarian modernist paradigm of the Soviet Union, where the ‘new man’ was constructed by repressing the ‘old man’ who was not the right material for such a construction process;

- the current Russian aggression which justifies the military incursion into peaceful territories by the fact that ‘fascism’ allegedly thrives on these territories.

The third point requires more attention. Just like a person with the assigned female sex at birth is recognised on the street as a woman regardless of her gender identity and level of commitment to feminism (at least before the visible gender transition is initiated), in the current hybrid war there are enough people willing to attack in one way or another those who are recognised (simply by their place of residence) as a Ukrainian regardless of the degree of commitment of that person to Ukrainian nationalism and self-identification as a Ukrainian.

Tetiana Zhurzhenko points out in her above-mentioned work that both feminism and nationalism in Ukraine consider themselves victims of Soviet policies. Indeed, the progress in gender equality announced in the early years of the USSR slowed down relatively quickly. After the Soviet annexation of Western Ukraine, the pre-war Ukrainian women's movement in the region ceased to exist and the group of feminists established in Leningrad in the late 1970s was expelled from the country[18]. Therefore, the analogy between gender and national identity seems to be a legitimate one. In fact, labelling oneself as belonging to a group defending itself is not automatically unacceptable, otherwise the slogan “Black lives matter” would also be unacceptable. The structured nature of ethnic violence expressed in military aggression (in Crimea this expands to Crimean Tatars, the ethnic group localised there) works as a sufficient factor of identification with the Ukrainian project.

Extreme nationalism promotes inequality and should be condemned, and if mixed with moderate democratic nationalism, neither condemning the first nor criticising the latter by the left will work. The generalised criticism of ‘nationalism’ in the reality of today’s Ukraine is insensitive to the specific context and interests of particular women and is an imported ‘westsplaining’ (akin to mansplaining)[19].

THE INVISIBLE BATTALION. ACHIEVEMENTS AND CRITICISM

Volunteer Lyudmyla Kalinina

The Invisible Battalion project[20], in which I am honored to work, emerged as a grassroots initiative of female volunteers in the ATO (anti-terrorist operation). They faced issues of inequality and invisibility (no provision existed for women in the legal framework and infrastructure of the Armed Forces of Ukraine to be enlisted in combat jobs in the real war). Female service members launched an advocacy campaign that included the Invisible Battalion sociological survey. The results of the five-year project were two studies (the second focused on the needs and concerns of women veterans), the adoption of a framework law that guaranteed equal service conditions for women and men in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, acceptance of girls to military lyceums, increased visibility of servicewomen in the media and two documentaries, Invisible Battalion and No obvious signs. The grassroots movement of servicewomen and veteran women also includes an international veteran diplomacy project, support for education for veteran women and men and community consolidation in general. Despite these significant successes, the project was criticised.

Read more in the article “How Women Changed the Ukrainian Army” by Hanna Hrytsenko.

Criticism from far right-wing movements that opposed the very subjectivity of women was predictable[21], but feminist criticism was also present. I can fully agree with the oral remark from the 2017 International Gender Workshop “Gender and (Military) Conflicts in Eastern Europe through a Feminist Lens” that the project calendar, created by some PR agency, preferred younger women when selecting photos and thus glamourised Ukrainian soldiers, among whom are older women or those who are not willing to conform to glossy beauty standards.

I can partly agree with Daria Popova's remark that the project is liberal[22]: breaking the formalised ‘glass ceiling’ belongs to both the liberal agenda, since it eliminates visible formal inequalities, and the left agenda. The Armed Forces of Ukraine are a big employer, and the fight with the ‘glass ceiling’ for equal working conditions is fundamentally not different from a trade union struggle. Salaries in the Armed Forces of Ukraine are relatively high and the formalisation of women's participation in service gives female soldiers access to economic independence. It also reduces the risks of domestic violence for them.

However, there are remarks that I cannot accept. Olga Plakhotnik and Maria Mayerchyk, for example, argue against[23] the Invisible Battalion study because it does not document that particular units of the Ukrainian army are accused of war crimes. In the text of the study and in its demographic annexes, the respondents are anonymised and numbered, and the names of the army units were removed from their quotes. Therefore, no one who was not involved in the study can know whether any of the female respondents belonged to the mentioned units, moreover whether they were somehow related to the war crimes which have not yet been proven in court. The project was also criticised because of nationalism, I have explained the problematic nature of such criticism above. Plakhotnik and Mayerchyk state that “the tactics of inclusion of women may also make recruiting the population to war easier”. The hidden implication that supposedly recruiting the population to a defensive war is something bad is a point towards which I have a fundamental value-based objection. It is also quite strange to read about the “mythologising, romanticising and heroising” of women in relation to the text that is entirely dedicated to legal and infrastructure issues. Given that the single quote in support of this view is taken from the cover of the study, I am not sure the opponents read it at all.

FEMINIST ANTIMILITARISM OR HIDDEN COLLABORATIONISM WITH THE AGRESSOR?

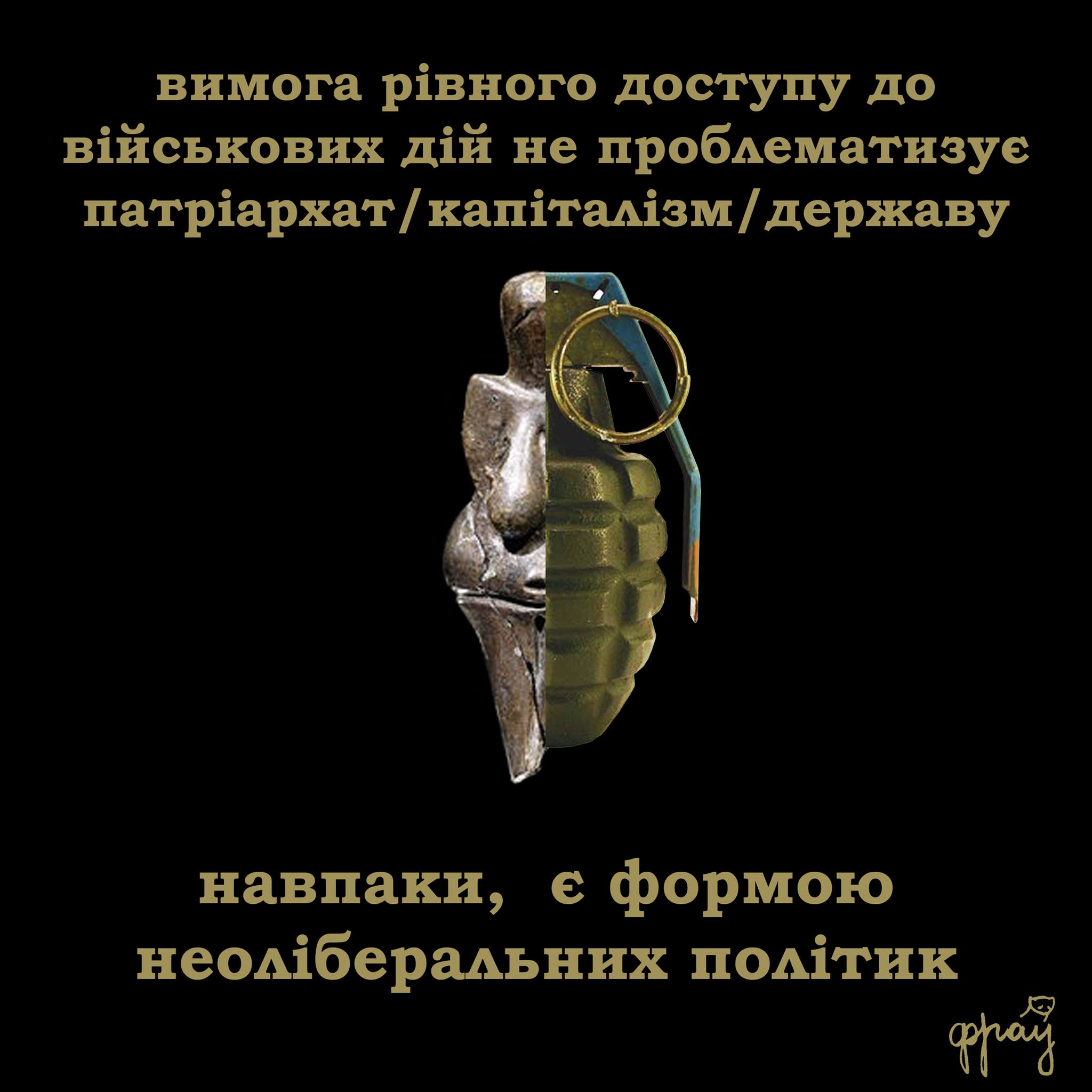

The FRAU art-group created a poster which points out that the demand for free access to warfare is a form of neoliberal policy.

Caption: the demand for equal access to warfare does not problematise patriarchy/capitalism/the state. On the contrary, it is a form of neoliberal policy

Unfortunately, there is no additional text in the picture which could explain the written argument. However, this wide interpretation of 'neoliberal policy' may include anything, even the struggle of nineteenth century Chicago workers for an eight-hour working day.

The Feminist Critique journal invited American feminist Cynthia Enloe, who researched the Soviet Union's militarism in the war in Afghanistan, to participate in a public discussion about women and war in Ukraine. In a 2018 talk to a Ukrainian audience[25] she gave the necessary warning: the nature of warfare may differ from country to country and the fight against sexism in the military is important, but in general she criticised militarism. Enloe understands this notion as a package of ideas[26] (I will explore them in more detail below) and therefore suggests that we must oppose it on the level of rethinking these ideas.

The advantage of this approach is a critical attitude to one's ideas about reality, while the disadvantage is that there is no procedure for confronting ideas with facts. Therefore, the discussion misses a ‘reality check’ on what exactly women—service members, war zone residents and internally displaced women—want. Enloe suggests neither looking for ways in which women in the war zone can explicitly promote their interests, nor trying to build more gender-sensitive public policy. The author of Nihilist website, a male anarchist, defines the epistemological position of the researcher as one based on the concept of sin (i.e. has no independent verification and has repressive potential)[27]. In my view this is a slight exaggeration: Enloe makes the necessary warnings, but her theorising still lacks bridges to practice.

Indeed, it is not entirely clear that Enloe's reasoning can be applied to the realities of Ukraine. She frankly says, “As an anti-militarist feminist, I want the army to be a less important institution within the broader confines of civil culture.” This may work well in a country which fights on foreign territory, but in a country that is defending itself, taking this position means coming over on the side of the aggressor and engaging in victim-blaming. As of 2020 there has been enough independent research which indicates that the reason for the military conflict in eastern Ukraine is Russian military aggression, while domestic linguistic, cultural, social and political differences were and remain part of Ukrainian diversity and that any discussion on this topic should begin with both sides agreeing on this premise.

In general, the expressed position which I call pacifist feminism comes from the privilege of not being directly affected by the conflict (US citizenship and residency in the US provide it for Cynthia Enloe, while efforts of women and men at the front line provide it for Ukrainian women). A similar view is shared by Dafna Rachok and Roman Leksikov, who point out that “the opportunity to engage in anti-war activism instead of being involved into hostilities is a privilege available only to those who (1) do not reside in the territory or country where active hostilities are taking place; (2) belong or identify themselves with the community that carries out military aggression and not with the one that is being targeted”[28].

Cynthia Enloe

I would also mention class and educational privilege: if a Ukrainian feminist has enough education and qualifications to go through the filter of emigration from Ukraine to war-free Western countries, if necessary, she can also afford not to care about war issues. However, this kind of feminism can hardly be called anything other than neoliberal, even if formally it declares something different. As a side note, I would like to point out that this version of feminism also ignores the experience of the Spanish Civil War women's movement Mujeres Libres, although it is Western, i.e. well known and studied, and explicitly anti-capitalist at the same time. I would absolutely welcome the pacifist feminism of Russian feminists in Russia who would struggle for the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine, but I know nothing about it, except for individual exceptions. A position of pacifism in Ukraine is a conscious or unconscious collaboration with those who started the war and continue creating problems for Ukrainian women.

From another perspective, an important characteristic of pacifist feminism is that it does not distinguish between active aggression and violence and does not take responsibility for its potential passive aggression. Let me present a lengthy quote from Judith Butler, “Aggression can and must be separated from violence (violence being one form that aggression assumes), and there are ways of giving form to aggression that work in the service of democratic life, including antagonism and discursive conflict, strikes, civil disobedience, and even revolution. Hegel and Freud both understood that the repression of destruction can only happen by relocating destruction in the action of repression, from which it follows that any pacifism based on repression will have simply found another venue for destructiveness and in no way succeeded in its obliteration. It would further follow that the only other alternative is to find ways of crafting and checking destructiveness, giving it a livable form, which would be a way of affirming its continuing existence and assuming responsibility for the social and political forms in which it emerges.”[29]

Bohachevsky-Chomiak reminds us that women's responsibility for peacemaking both does not work and can be a means of putting pressure on them. She writes that before the First World War, middle-class women activists created the International Council of Women as a peacemaking initiative, but it turned out to be inefficient. Four generations later, says the researcher, in Sarajevo where the First World War started, at the 1992 International Women's Forum, a German participant blamed women for the failure to preserve peace in the Balkans[30]. In the context of debates on ‘militarism’ and colonialism, Madina Tlostanova analyses the case of Nawal El Saadawi, a feminist of Arab origin who refused to be a ‘peacemaker’ and ‘postmodernist thinker’ because of the US-centric meaning of these terms and was therefore restricted in her right to public presence and sometimes demonised as a supporter of terrorists. At both poles of this binary, this woman's subjectivity was not taken into account, her ideas were not heard, she was pigeonholed into a standard explanatory scheme[31].

Equally, we must not reduce the reasons for women's participation in military activities to nationalism or militarism as a set of ideas (although this reason may work too). The Invisible Battalion female respondents reported in particular that they had lost their jobs because of the war or that they went to the front to follow their family members. Analytical approaches to women's participation in warfare must not devalue from a privileged position the practical decisions taken by women affected by war, nor should their behaviour be reduced to the mere performance of combat tasks. According to recent data, approximately 55,000 women are currently employed in combat and non-combat jobs in the Armed Forces of Ukraine[32]. Psychological explanatory schemes that ignore the conducted research work poorly for such a large sample size.

Anti-militarism, according to Enloe, is a refutation of militarist ideas, which in Ukraine are refuted anyway, by ‘militarism’ itself. The broad participation of women in the uniformed agencies weakens the idea that only men can make war (female respondents of the Invisible Battalion project, who countered gender stereotypes of fellow men by their own example confirm this idea) and that women need male protection. An indirect result of the campaign was that the media started to give a more accurate image of women in the army, the question of women's access to 450 civilian professions was raised and resolved, and later LGBT men and women in the military launched the campaign for their visibility. If a heterosexual man at the front defends his wife, whom does a gay man defend?

Another of Enloe's ideas, that a man who refuses to make war undermines his masculinity, also does not work properly in Ukraine: before the war one could and should defer from compulsory military service, and hence masculinity as such was constructed around the actual willingness to use aggression rather than the fact of formal participation in aggressive institutions. The same question applies to the open gay in the military: does he reproduce traditional masculinity or undermine it?

CONCLUSIONS

The feminist attitude to war issues often seems to be pacifist and to echo the patriarchal division between men who fight and women who pacify them, only the rationale differs. In Ukraine during the war, this attitude is present but is not dominant among Ukrainian feminists.

Since the very beginning of the Russian aggression in Ukraine, post-Soviet feminists’ attitudes have been divided. Some public Russian feminists have openly supported the aggression, while others’ attitude has been that war is ‘man's games’ and women have no conflict of interest here. War leads to both direct sexual abuse on the part of combatants of all sides of the conflict and an increase in prostitution in the ‘grey zone’. This feminist attitude does not respect the interests of other women.

Overall, the war can end in different ways and at different costs. Leaving certain areas of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts and Crimea under occupation means a significant reduction in the quality of life for those who still live there, even if there is a ceasefire. In addition to their quality of life, there are also values, so those women who have not been directly harmed or abused also have a right to demand the cessation of hostilities under Ukrainian conditions. Calling anything that’s not pacifism by the term nationalism in the negative connotation of the word is a simplistic and often harmful understanding of the events in eastern Ukraine and a simplistic understanding of nationalism as a phenomenon.

Instead of devaluation, feminists should focus on solidarity practices and develop consensus-based solutions. A liberal feminist minimum on combating violence during the war and discrimination in the army might become a compromise between different factions of feminism.

Cover photo: Olena Angelova

Photo: Gender in Detail, Kleopatra Anferova / The Invisible Battalion, Feminist Critique

Translated from Ukrainian by Iryna Malishevska.

[1] Доброта, Валентина. Сексуальне насильство під час війни — це військовий злочин. Інтерв’ю з Катериною Левченко // http://bilahata.net/seksualne-nasylstvo-pid-chas-vijny-tse-vijskovyj-zlochyn/

[2] Виртосу, Ірина. Війна, яка не відпускає. Про домашнє насильство в сім’ях АТО. 4 липня 2016 року // https://life.pravda.com.ua/society/2016/07/4/214486/

[3] https://feministki.livejournal.com/3371586.html

[4] https://feministki.livejournal.com/3626725.html?thread=223246821#t223246821

[5] https://feministki.livejournal.com/3626883.html?thread=223257475#t223257475

[6] https://feministki.livejournal.com/3638389.html?thread=224270197#t224270197

[7] https://feministki.livejournal.com/3638389.html?thread=224363125#t224363125

[8] https://maryxmas.livejournal.com/3603734.html

[9] Журженко, Тетяна. «Небезпечні зв’язки»: націоналізм і фемінізм в Україні // Україна. Процеси націотворення. — К.: К.І.С., 2011. — С. 140.

[10] Тлостанова, Мадина. Деколониальные гендерные эпистемологии. — М., 2009. — С. 81–82.

[11] https://www.colta.ru/articles/society/17531-moe-voobrazhaemoe-puteshestvie-v-l-dnr

[12] https://www.facebook.com/groups/feminism.ua/permalink/1512693872094980/

[13] Ibid.

[14] Плахотнік Ольга, Маєрчик Марія. Між колоніальністю і націоналізмом: генеалогії феміністичного активізму в Україні. 2019 // https://genderindetail.org.ua/season-topic/gender-after-euromaidan/mizh-kolonialnistyu-i-natsionalizmom-genealogii-feministichnogo-aktivizmu-v-ukraini-1341124.html

[15] Brubaker, Rogers. Nationalism Reframed. Nationhood and the national question in the New Europe. — 1996.

[16] Богачевська-Хом’як, Марта. Націоналізм і фемінізм: провідні ідеології чи інструменти для з’ясування проблем? // Гендерний підхід: історія, культура, суспільство / За ред. Ліліани Гентош, Оксани Кісь. — Львів: ВНТЛ-Класика, 2003. — С. 166–167.

[17] https://www.facebook.com/groups/feminism.ua/permalink/1512693872094980/

[18] More on this story: Толстой, Иван. 1980-й. Высылка советских феминисток. 2010 // https://www.svoboda.org/a/2170370.html

[19] http://euromaidanpress.com/2020/06/19/westsplaining-ukraine/

[20] Марценюк Тамара, Квіт Анна, Гриценко Ганна. «Невидимий батальйон»: участь жінок у військових діях в АТО (соціологічне дослідження). — К., 2015.

[22] Попова, Дарія. Война, национализм и женский вопрос. 2017 // https://commons.com.ua/ru/vijna-nacionalizm-ta-zhinoche-pitannya/

[23] Плахотнік Ольга, Маєрчик Марія. Між колоніальністю і націоналізмом: генеалогії феміністичного активізму в Україні. 2019 https://genderindetail.org.ua/season-topic/gender-after-euromaidan/mizh-kolonialnistyu-i-natsionalizmom-genealogii-feministichnogo-aktivizmu-v-ukraini-1341124.html

[25] Енло, Синтія. Розплутати клубок мілітаризму: феміністичний аналіз і спротив // Критика феміністична. — 2019. — — № 2: https://feminist.krytyka.com/ua/articles/rozplutaty-klubok-militaryzmu-feministychnyy-analiz-i-sprotyv

[26] Enloe, Cynthia. Understanding Militarism, Militarization, and the Linkages with Globalization. // Gender and Militarism. Analyzing the Links to Strategize for Peace. — 2014. — Р. 7–9.

[27] Кутній, Сергій. Магічний антимілітаризм і альтернативні факти. 2019 // https://www.nihilist.li/2019/06/18/magichnij-antimilitarizm-i-alternativni-fakti/

[28] Рачок Дафна, Лексіков Роман. За межами теорій із Заходу: про вжиток і зловжиток «гомонаціоналізму» в Україні. 2020 // https://genderindetail.org.ua/season-topic/gender-after-euromaidan/za-mezhami-teoriy-iz-zahodu-pro-vzhitok-i-zlovzhitok-gomonatsionalizmu-v-ukraini-1341458.html

[29] Батлер Дж. Фрейми війни: чиї життя оплакують? — К., Медуза, 2016. — С. 99.

[30] Богачевська-Хом’як, Марта. Націоналізм і фемінізм: провідні ідеології чи інструменти для з’ясування проблем? // Гендерний підхід: історія, культура, суспільство / За ред. Ліліани Гентош, Оксани Кісь. — Львів: ВНТЛ-Класика, 2003. — С. 177.

[31] Тлостанова, Мадина. Деколониальные гендерные эпистемологии. — М., 2009. — С. 48.

[32] В українській армії служать 55 тис. жінок, — Порошенко // https://censor.net.ua/ua/news/3091255/v_ukrayinskiyi_armiyi_slujat_55_tys_jinok_poroshenko