Translated from Ukrainian by Iryna Malishevska.

Identity Rediscovered: Women’s Activism — from the Revival of Feminist Consciousness to Feminist Action

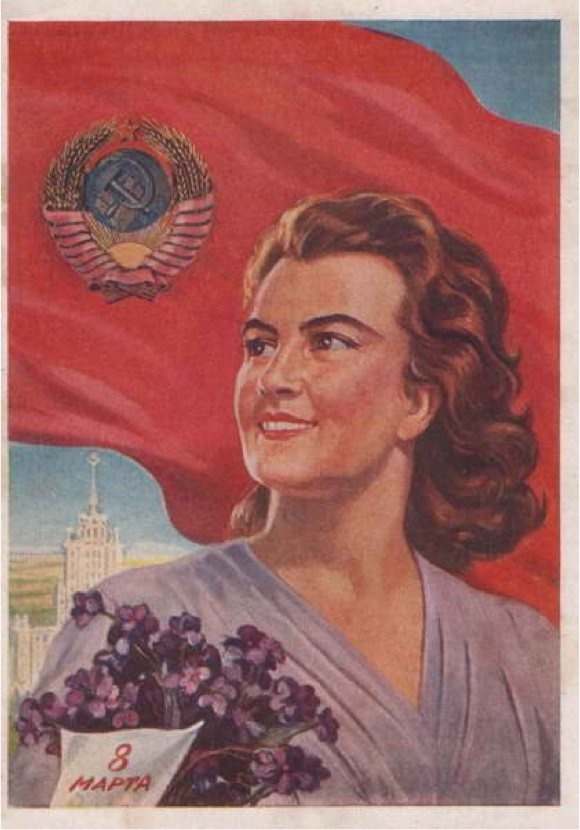

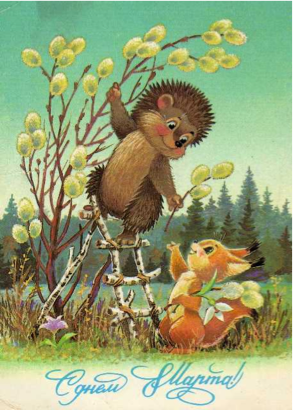

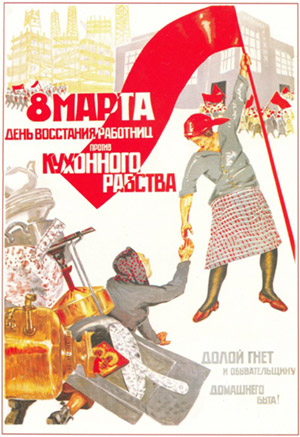

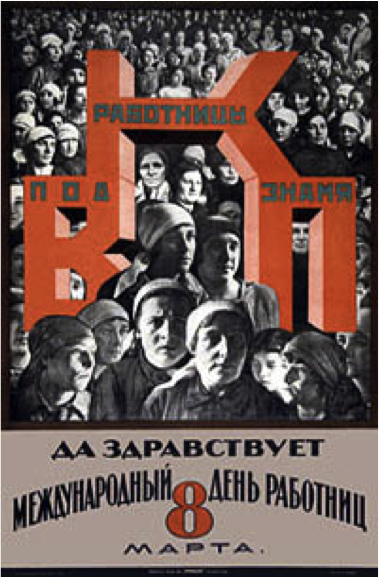

The annual celebration of International Women's Day on March 8th played a meaningful role in the boost of feminist consciousness in women's activism[1]. In post-Soviet Ukraine, this Soviet holiday proved to be the most enduring of all the ‘red-letter days’[2]. During the twentieth century, its original meaning became distorted: its feminist essence of women’s solidarity in their struggle for equal rights was eviscerated and the day was used to promote the Soviet way of life. In the 1980s, the holiday turned into ‘a holiday of spring, beauty, love and eternal femininity’ — a kind of mix of Valentine's Day and Mother's Day.

Soviet citizens became used to celebrating the holiday boisterously with their colleagues and families, showering with gifts and honouring women once a year for their feminine traits and virtues. Meanwhile, Soviet leaders started a tradition of congratulating women in public on this day. In their speeches, they emphasized the numerous advantages of living under socialism and gave no attention to various forms of discrimination[3].

Discover more on the transformation of the meaning of March 8 in Oksana Kis’s article “Rights and Tulips: Why Do We Still Celebrate the 8th of March?”

Despite the post-Soviet transition in official ideology, leaders at all levels in independent Ukraine continued these traditions. Representatives of opposing political parties were unanimous in their conservative vision. They glorified women for their role in the family and feminine charms and congratulated them on springtime[4].

The last straw for feminists was Viktor Yushchenko’s speech in March 2008:

Dear Ukrainian Women! Greetings on the occasion of the holiday of spring, the holiday of women’s beauty, which blossoms in Ukraine today. My heart is filled with the most tender feelings for you. We love you, we respect you and we are thankful to you all — our mothers, wives, beloved ones, friends, daughters, to all the most important women in our life. My greetings on this holiday of love and hope, Ukrainian women, the most charming and best women in the world![5].

This clearly essentialist rhetoric (with family roles and eternal feminine virtues as women’s only value) deeply disappointed all those who had believed the President was a loyal supporter of the idea of gender equality ever since he had highlighted his allegiance to democracy and signed the Law of Ukraine “On Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men in Ukraine” (2005). Exasperated by his hypocrisy, Ukrainian women (activists, scholars, and experts) published an open letter to the head of the state in which they refused to recognize themselves as the ‘weaker and fairer sex’. These successful women noted his emphasis on purely ‘feminine virtues’ and demanded to be seen as full-fledged citizens appreciated for their professional, intellectual, creative and political achievements, and to enjoy gender equality in all areas instead of being greeted upon the arrival of spring[6].

Despite this, political leaders continued making one sexist statement after another:

― “introducing reforms isn’t women’s business” (Mykola Azarov, Prime Minister of Ukraine, March 2010);

― “when it gets warm and women start wearing less clothes in Ukrainian cities, it is wonderful” (Viktor Yanukovych, President of Ukraine, January 2011);

― “women alone should do all the housework” (Iosyp Vinsky, MP, February 2011);

― “the true calling of a woman is to be a mother and guardian of the family hearth” (Volodymyr Lytvyn, Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada, March 2011).

Lytvyn took it a step further when commenting on the need for political quotas:

A man is a higher being, since a woman was made from Adam's rib. Hence, she is a lesser being,

so involving women in politics is unnatural[7].

There was an immediate strong response to this insolent attack: an open letter from over two dozen women's NGOs was published in the media[8]. This was noteworthy because, for the first time in the history of independent Ukraine, local and diaspora women's organisations with different areas of focus spoke with one voice and showed their solidarity in opposing sexism. This should have sent a signal to the Ukrainian government, which for decades had managed to play a double game of paying lip service to gender equality while passing most of its work on the public sector[9].

Around this time feminist street activism was born in Ukraine. The first March 8 feminist march took place in Kyiv in 2008 at the initiative of the “Svobodna” (“free”) anarchist feminist collective. From 30 to 40 people marched along Khreshchatyk Street that day.

March in 2008

Hanna Hrytsenko “Marches on March 8: the Rise of a Feminist Tradition”

Oksana Kis “Stolen Holiday: Historical Transformations of the Meaning of March 8”

2009 was a turning point, with various forms of protest actions taking place in several big cities (Kharkiv, Lviv, Chernivtsi) at the initiative of local women’s unions.

March in 2009, Lviv

The significance of these events for the Ukrainian women's movement can hardly be overstated. For the first time ever, Ukrainian feminists entered the public space to draw the attention of a general audience (and not just a narrow circle of female researchers, activists, or officials) to the problem of pervasive gender discrimination[10].

Educational, cultural, social, and political actions on the International Day of Women's Rights became mass events and received broad media coverage in 2010–2011 thanks to the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the holiday[11]. The first open feminist march with the slogan “March 8 is a political holiday” took place in Kyiv in 2011 at the initiative of Feminist Ofenzyva, an association of feminist groups.

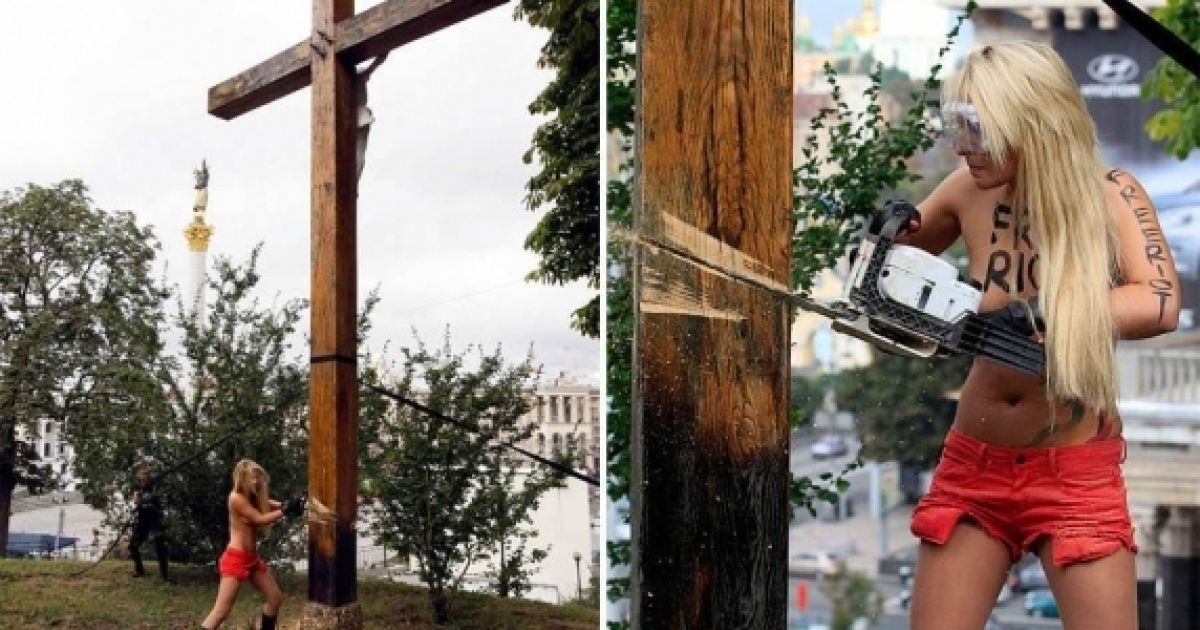

When talking about women’s activism of this period, we must mention the FEMEN movement, which emerged in 2008 and became well-known in Ukraine and worldwide due to its peculiar form of protest. Young, attractive activists performed their protests topless. We should point out that in Ukraine FEMEN (represented by their leader Anna Gutsol) disassociated themselves from feminism. It was only after their political immigration to Western Europe in 2013–2014 that the group’s press kit started to include the word ‘feminism’.

Ukrainian female researchers of the women’s movement and activists of other NGOs had mixed feelings toward FEMEN’s activities, from complete support to harsh criticism and disapproval[12].

Not all of FEMEN's actions display a clear connection between the form of the protest and the problem it highlighted. Initially, the women’s slogan was “Ukraine is not a brothel”. They protested against prostitution, sex tourism, and the sexual exploitation of women with their naked bodies as a tool of protest. This shocked audiences, drawing attention to the problem. But when they began performing topless in relation to the swine flu or the defeat of the Ukrainian team at the Olympics, their form of protest seemed questionable. The female body cannot be the only instrument of protest, and provocation cannot be the only way to fight back. The FEMEN movement was entirely discredited when its members took part in an erotic photo shoot for Loaded men’s magazine. History shows that this movement was unsustainable, and while its followers still organise some stunts in different countries, the media do not take much interest in their activities anymore[13]. FEMEN never became part of the Ukrainian women's movement — in part because of their deliberate self-isolation (activists did not try to get in touch or cooperate with other organisations) and a lack of any clear feminist agenda, and also because the initiative to establish and maintain the group didn’t come from its members. The hard-hitting documentary Ukraine is not a brothel (2013), directed by young Australian journalist Kitty Green, reveals that the organiser and director of all FEMEN protests was a certain Viktor Sviatsky, who took advantage of the girls, who were dependent on him[14].

Due to broad media coverage, the general public began to associate FEMEN protests with feminism in general (some still write “femEnism”). For this reason, the activities of other feminist organisations which actually work on the numerous issues facing Ukrainian women, started to be perceived as extravagant ‘sextremists’. At the same time, the FEMEN phenomenon has led to serious discussions within the Ukrainian women's movement about the limits of feminism, means of reaching feminist ends, and their cost.

The activities of Feminist Ofenzyva provide a good illustration of how feminist consciousness/identity grew into feminist action[15]. A separatist grassroots women's initiative published the Feminist Ofenzyva Manifesto, which sharply criticised today’s patriarchy and celebrated the principles of intersectional feminism. Throughout its existence between 2010 and 2014, the group organised several feminist-oriented scientific and cultural events, as well as mass street marches[16]. The activities and programme documents of Feminist Ofenzyva show the organisation to have been quite radical and revolutionary; they refused any form of cooperation with the authorities and strove to change the existing patriarchal system of society.

Initiatives by Feminist Ofenzyva

The development of a full-fledged women’s movement in Ukraine culminated in the founding of Feminist Ofenzyva. Currently, the movement is represented by a variety of organisations from the most conservative (traditionalist) to the most radical (queer and anarcha-feminist), including a large segment of liberal feminist groups. This variety can be seen in the informational projects on gender issues developed in the 2010s. Povaha, WOMO, TheDevochki, Update, Gender in Detail, 50 percent, “Ya” Journal, Feminist Critique, Feminism.UA Facebook group have substantial ideological differences.

At the same time, a clear specialisation among actors of the women's movement took place, with political, social, human rights, educational, research, professional, cultural, and other areas of focus. LGBT organisations, such as “Insight” NGO[17], play a notable part in feminist activism. The organisation provides assistance and support to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex individuals and advocates for human rights and education. In particular, it has been co-organising feminist and women's marches in Kyiv for many years. It is worth mentioning the Kharkiv women's association “Sphere”[18], which was born as an informal lesbian initiative in 2001 and became one of the most powerful LGBT and feminist organisations in eastern Ukraine over its 18 years of existence.

A number of explicitly feminist initiatives emerged in various Ukrainian cities after the Revolution of Dignity, whose female leaders and participants demonstrated exceptional egalitarianism, openness, inclusivity, and creative strategies. Among them is Feminist Workshop, which was created in the summer of 2014 as an informal feminist initiative within the Ukrainian Catholic University and later evolved into an independent NGO. Its activists engage people of different ages, genders, educational levels, and professions in different activities of different formats and subject matter (creative, educational, protest, cultural events, etc.)[19].

Serious ideological debates demonstrate the maturity of the Ukrainian feminist movement. One passionately debated issue is the problem of prostitution: whether sex work should be decriminalised or, on the contrary, the client should face criminal charges (the Swedish model). Furthermore, there is no consensus among feminists on the possible (non)participation of transgender women in the women's movement. Feminist communities in social media, especially Feminism.UA (administrated by Maria Dmytrieva since 2011 with about 9 thousand members currently) and Resistanta (a smaller and younger Facebook group with a more radical community; administrated by Olena Zaitseva), have become platforms for such discussions, which are often heated, but generally productive. The role of the Internet and social media in spreading feminist ideas, articulating issues important to women, mobilizing the feminist community and nurturing solidarity cannot be overstated. A vivid example are feminist flashmobs on Facebook, which quickly reach a huge audience. For example, in 2016 two flashmobs were initiated by well-known feminist activists. The first flash mob with the hashtag #ЖінкаЯкаНадихає (#aWomanWhoInspires) was initiated by Tamara Zlobina, who invited people to move away from the commercialised Soviet tradition of celebrating International Women's Day and suggested they fill the social and mass media space with success stories of female role models. In July of the same year, Nastia Melnychenko launched the campaign #яНеБоюсьСказати (#I'mNotAfraidToSay) and broke the cultural taboo of talking about sexual abuse by significant others as the private unspoken experience of many women. As a result, thousands of women's open and painful stories appeared online, demonstrating the scale and depth of the problem, which one is “not supposed to talk about”.

Prejudice and hostile attitudes towards feminism in Ukrainian society are decreasing in proportion to the increased spread of knowledge about feminist ideology and activism and feminist studies. Ukraine has already amassed a wealth of knowledge in scholarly publications on feminism and gender issues (translations of classic works as well as Ukrainian studies in various fields). At the same time, gender education is nurtured by popular science and journalism publications. They convey ideas of gender equality in a clear way, present the facts of gender discrimination, describe the foundations of the feminist movement, explain the diversity of feminist schools, and reveal the historical and cultural contexts of the development of feminism in different countries at different times[20]. In addition, media are showing a growing interest in this topic and have been publishing interviews with activists and inviting them on radio and TV shows, which has helped dispel the rather ‘demonized’ image of feminists among the general public, replacing it with a clearer understanding of the key tenets of feminism.

In the summer of 2017, the Ukrainian Women's Fund conducted a large-scale survey among women's activists to assess the development of the women’s movement in Ukraine. The results revealed both strengths and weaknesses and showed that the organisations are ready for deeper consolidation and collaboration[21]. Obviously, as with any other movement, there is no unanimity and never will be among Ukrainian feminist organisations as to ideological principles, top priorities and minor tasks, types of activities and approaches, methods for reaching goals, etc. However, they all have one thing in common: they acknowledge the discrimination of women prevalent in today’s Ukraine and agree on the need to change the status quo.

Summary

According to a survey from 2012, almost one-tenth of Ukrainian women consider themselves feminists[22]. The situation has changed markedly since the 1990s, but remains ambiguous. Nowadays we live in a society in which the dedicated work of women’s NGOs has paved the way for gender equality. At the same time, the term ‘gender’ has been defamed by conservative actors. Despite their attacks and officials’ ignorance and patriarchal attitude, there is room for optimism. In any event, the Ukrainian state must fulfill its international obligations relating to gender equality or face international isolation. Feminist initiatives are growing and getting stronger in all areas of public life, and the feminist movement is becoming more sizeable and ideologically diverse. We are finally able to ‘say it like it is’[23]. And thus we call the fight against discrimination against women in Ukraine feminism, and the analysis of origins, acts and mechanisms of patriarchy feminist studies.

Translated from Ukrainian by Iryna Malishevska.

[1] See the overview of events that demonstrate the revival of the genuinely political (feminist) meaning of the holiday of March 8: Kis, Oksana. Ukrainian Women Reclaiming the Feminist Meaning of International Women’s Day: A Report about Recent Feminist Activism // ASPASIA: International Yearbook of Central, Eastern and Southern European Women’s and Gender History. — 2011. — № 6. — Р. 219–232.

[2] Sociological surveys conducted in 2004 and 2008 in Lviv and Donetsk showed that citizens of both cities continue to actively celebrate March 8 (Donetsk: 91,0% and 86,1% respectively; Lviv: 64,5% and 53,4% respectively). The database: Грицак Ярослав, Маланчук Оксана, Черниш Наталя, Середа Вікторія, Сусак Віктор. Львів—Донецьк: Соціологічний аналіз групових ідентичностей та ієрархій соціальних лояльностей (1994, 1999, 2004; вибірка: 400+400).

[3] For more details refer to: Кісь, Оксана. Украдене свято: історичні трансформації смислу 8 Березня // dt.ua. — 2013. — 6 березня; Карпова Галина, Ярская-Смирнова Елена. Символический репертуар государственной политики: Международный женский день в российской прессе, 1920–2001 // Социальная история: Ежегодник 2003. Женская и гендерная история / Ред. Н. Л. Пушкарева. — М., 2003. — С. 488–509; Chatterjee, Choi. Celebrating Women: Gender, Festival Culture, and Bolshevik Ideology, 1910–1939. — Pittsburgh, 2002.

[4] You can find individual cases of such greetings here: Kis, Oksana. Choosing without Choice: Predominant Models of Femininity in Contemporary Ukraine // Gender Transitions in Russia and Eastern Europe / Ed. M. Hurd, H. Carlback, S. Rastback. — Stockholm, 2005. — P. 112–113; Kis, Oksana. “Beauty Will Save the World!” Feminine Strategies in Ukrainian Politics and the Case of Yulia Tymoshenko // Spaces of Identity. — 2007. — Vol. 7. — № 2. — P. 67.

[5] Вітання Президента України Віктора Ющенка з нагоди 8 Березня // www.president.gov.ua

[6] Відкритий лист Президентові України // http://zgroup.com.ua. — 2008. — 18 березня.

[7] Литвин пояснив гегемонію чоловіків у політиці «еволюційною вищістю» // http://tsn.ua. — 2012. — 2 березня.

[8] Лист жіночих громадських організацій голові Верховної Ради України // http://gender.at.ua. — 2012. — 6 березня.

[9] For a typical example, refer to the situation of domestic violence prevention which was addressed comprehensively by Alexandra Hrycak in the following publication: Hrycak, Alexandra. Transnational Advocacy Campaigns and Domestic Violence Prevention in Ukraine // Domestic Violence in Postcommunist States / Ed. K. Fabian. — Bloomington, 2010. — P. 45–77.

[10] For more details refer to: Kis, Oksana. Feminism in Contemporary Ukraine: From “Allergy” to Last Hope // Kultura Enter. — Lublin, 2013. — Vol. 3. — Р. 264–277.

[11] See: Kis, Oksana. Ukrainian Women Reclaiming the Feminist Meaning of International Women’s Day: A Report about Recent Feminist Activism // ASPASIA: International Yearbook of Central, Eastern and Southern European Women’s and Gender History. — 2011. — № 6. — Р. 219–232; Гриценко, Ганна. Марші 8 Березня: винайдення феміністичної традиції // https://genderindetail.org.ua. — 2018. — 16 березня.

[12] For example, refer to the articles by Maria Dmytrieva (https://krytyka.com/ua/articles/femen-na-tli-hrudey), Larisa Lisiutkina (https://krytyka.com/ua/articles/fenomen-femen-malyy-vybukhovyy-prystriy-made-ukraine), Olga Plakhotnik and Maria Mayerchyk (https://m.krytyka.com/ua/articles/radykalni-femen-i-novyy-zhinochyy-aktyvizm).

[13] https://femen.org/

[14] See the official trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OHyPSREmeRA

[15] For more information refer to: http://ofenzyva.wordpress.com

[16] Ibid.

[17] https://www.insight-ukraine.org/uk

[18] http://sphere.org.ua/history-of-sphere/

[20] Т. Марценюк. Гендер для всіх: виклик стереотипам. К., 2017; Т.Марценюк. Чому не варто боятися фемінізму. К., 2018

[21] Сучасний жіночий / феміністичний рух в Україні: погляд зсередини // www.uwf.org.ua

[22] The survey was taken by the NewsEffector monitoring agency together with the Integration Fund (the Russian Federation). The survey involved 8 400 participants aged between 18 and 55. The survey was taken on August 6–17, 2012 in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Refer to: В Україні більше феміністок, ніж у Росії і Білорусі (опитування) // www.unian.ua. — 2012. — 17 серпня.

[23] See: Павличко, Соломія. «Фемінізм — непоганий інструмент, щоб назвати речі своїми іменами» // www.day.kiev.ua. — 1998. — 13 червня.