Translated from Ukrainian by Iryna Malishevska.

The beginnings of democratic transition in all the post-socialist countries had much in common, including ‘being allergic to feminism’[1]. Distorted by communist propaganda about the ‘decaying West’ and discredited by Soviet practices, the ideas of feminism were not well-received, since Soviet women believed that they were the most empowered in the world, with their emancipation granted by the state. Even the activists of the new women's organisations shared this view on feminism as something alien and ‘extremist’.

If the ‘first wave’ of feminism, the suffragette movement as a struggle for basic political and economic rights, reached Ukraine synchronously with the rest of the world at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, Ukrainian women missed out on the ‘second wave’ in the 1960s and 1970s, because of the ‘iron curtain’. The ideals of equality declared by the Soviet authorities were implemented in an ambivalent way. On the one hand, women in the Soviet Union had full civil rights, access to education and professional work (while European women struggled for the right to dispose of their property and to vote until the mid-20th century). On the other hand, a public debate about acts of discrimination in a totalitarian society was out of the question.

In Europe and North America, it was ‘second wave’ feminist activism which led to social changes and the establishment of women's and later gender studies in universities and their further formalisation into an independent field of humanities in the 1980s–1990s. This process was different in Ukraine. The early 1990s could be considered a time of academic activism: women academics were in a hurry to adopt the achievements of Western feminist studies and establish academic centers and periodicals in order to share this knowledge. For women's organisations, the years 1990–2000 were a time to reflect on their own strategy and political positioning. This period was characterised by a rather conservative view of women, with their role as mothers dominating, and by the active cooperation of women's NGOs and the state in order to change legislation and make desirable changes. At the end of the 2000s, the Ukrainian women's movement became increasingly critical of the establishment in power and the first feminist street actions began to take place.

The events of the Revolution of Dignity intensified all social processes, among them the gender equality movement and advocacy for ‘traditional values’.

FOUNDATIONS OF UKRAINIAN FEMINISM

When analysing the process of feminism's ‘sprouting’ in independent Ukraine, let’s remember that it should not be considered as something alien: feminism put down deep roots and gave abundant seedlings in Ukrainian science and public life a hundred years ago. A powerful women's movement in Halychyna and Dnieper Ukraine in the early 20th century was feminist by its nature and consequences (although, perhaps, its declared aims and form were not). Since the Ukrainian nation did not have statehood, women's organisations of that time defined the rise of the national consciousness of the Ukrainians and the development of national culture as their main priority. The interests of women's emancipation were subordinated to the interests of the emancipation of the nation on purpose. However, the work of these organisations encouraged women's participation in public processes, which required higher education, professional work, being politically active, and having civil rights in general. Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak called this phenomenon ‘pragmatic feminism’.

Nataliya Kobrynska, Ukrainian writer and organiser of a women’s movement, and Milena Rudnytska,

head of the main branch of the Ukrainian Women's Union and pioneer of Ukrainian feminism

‘Feminists despite themselves’ is another of her apt expressions, but many activists, Nataliya Kobrynska and Milena Rudnytska among them, were into the topic of women’s emancipation quite consciously[2].

Similarly, Ukrainian historians, ethnographers, and folklorists showed an active interest in women's studies since the mid-19th century, and by the beginning of the 20th century, we find research into women's studies in the work of prominent researchers of the Ukrainian past (Ivan Franko, Petro Chubynsky, Volodymyr Hnatiuk, Fedir Vovk, Oleksandra Yefymenko, Petro Ivanov, Volodymyr Okhrymovych, Mykola Kostomarov, Kost Levytsky among them). “On the Study of Sexual Communities in Primitive Society” (1929)[3], a landmark article by Kateryna Hrushevska, can be considered a real manifesto of feminist criticism in humanities [4]. In fact, Hrushevska was two decades ahead of world feminist thought, since she expressed ideas that would later form the basis for Simone de Beauvoir's major work The Second Sex (1949).

“... historical science tries to explain women outside of a cultural context (...) Owing to the circumstances this ‘manly’ world—men’s social aspect of culture—was explored more deeply, this gives the impression that it is a real norm while the women’s world (…) is a mere variation, an episode, a ‘fragment’...”

– Kateryna Hrushevska.

Despite the emancipatory idea to ‘liberate women from kitchen slavery’ that the Bolsheviks had declared, the women's movement and women's studies in the Soviet Union collapsed. All memory of the struggle of socialist women in the Russian Empire before the October Revolution was extinguished, and the activities of the Ukrainian Women’s Union and other Ukrainian women's organisations of inter-war Halychyna were labeled as ‘bourgeois nationalism’. The ‘women's question’ was discussed only in the context of ‘plans for the building of communism’ and was considered solved, despite many real problems. Declared equality at the time of real discrimination and the impossibility of discussing women's life freely have affected the ability of Ukrainian women to think critically about their social status for many decades.

It was not until the early 1990s that pre-Soviet women's organisations resumed their activities in Ukraine and new ones popped up. At the same time, women's and gender studies emerge and develop. As in other countries, in Ukraine activism and research related to discrimination against women are closely intertwined; therefore, we can distinguish between feminism as a research strategy and feminism as a social movement only nominally for the sake of analytical purposes.

Given the lack of women's studies into the plight of women, the first activists in post-Soviet Ukraine had to conduct research on their own and thus they became researchers; at the same time, women scientists got actively involved in the work of NGOs to find social support for their work. The first research centres were established (and some still exist) as NGOs, while women's organisations often supported scientific and educational projects.

The women's movement and women's studies in Ukraine have another feature in common, a difficulty with the term ‘feminism’. Due to a lack of proper knowledge about feminism as an ideology and methodology, a variety of fearmongering stories about feminism spreading in society and academia in the early 1990s raised prejudice against the concept and even reluctance towards the term. To avoid confrontation and not to waste energy for ‘justifying feminism’, neither activists nor academics dared to identify themselves as feminists in public for a long time, although most of them used feminist strategies in practice in their work. Back then, the word ‘gender’—unknown and relatively neutral (no undesirable political connotations and emotional baggage)—became a convenient euphemism that postponed lively public and academic debate. Yet, this seemingly good tactical move has had unintended consequences for both the women's movement and studies focused on gender inequalities.

ACADEMIC FEMINISM: CATCHING UP TO AND OVERTAKING THE WEST

The early sign of feminism in the academic sphere was Solomiya Pavlychko's keynote article “Do Ukrainian literary studies need a feminist school?” (1991)[5]. In the article, the author articulated the fundamentals of feminist studies and also raised a critical question of the immediate inclusion of feminist methodology into research on social sciences and humanities in Ukraine, since without it “our culture will never become normal, European and complete”[6]. For the whole decade, Solomiya Pavlychko became the main voice of feminism in Ukraine and nearly the only Ukrainian scholar to present her own research on the situation of women in contemporary Ukraine to the international community[7].

Solomiya Pavlychko’s works

Catching up

The early years of women's and gender studies (1991–1994) can quite literally be called a period of catch-up. Scholars suddenly discovered a huge interdisciplinary field of research with its own developed analytical tools, scientific institutions, academic communities, and specialised professional periodicals. This made Ukrainian women academics desperately seek ways of self-education in order to master the theoretical and methodological achievements of Western gender studies. The task of ‘catching up to the West’ became almost ‘mission impossible’ due to a number of reasons: no access to even classic works on feminist and gender theory, a lack of funds to participate in international scientific events, informational isolation, the language barrier, and prejudices of the Ukrainian academic environment towards women's studies. However, some (e.g. Solomiya Pavlychko, Svitlana Barkhatna, Lyudmyla Smolyar, Oksana Malanchuk-Rybak, Nataliya Chukhym, and others) managed to accomplish the mission at least to some extent.

Read more about the beginnings of gender studies in the interviews with Svitlana Oksamytna, Tamara Hundorova, Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak, Marian Rubchak.

GATHERING STRENGTH

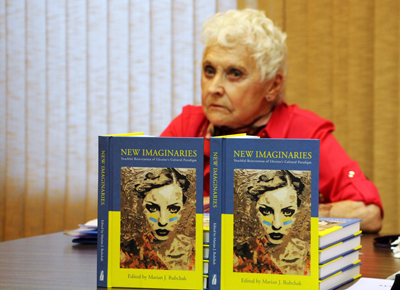

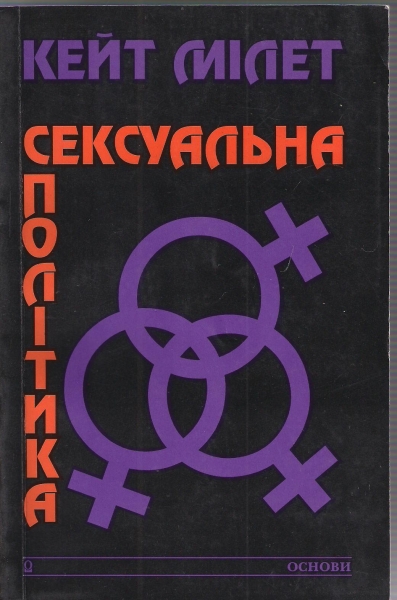

The following years (1995–1999) allowed for the gathering of strength and starting institutionalisation of women's and gender studies in Ukraine. A number of independent centres of gender studies were established (Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, Lviv)[8], several all-Ukrainian scientific conferences were held, and the first translations of classic works of feminist thought (Simone de Beauvoir, Kate Millett, Bethke Elstein, Martha Bohachevsky-Chomiak, and others) were published.

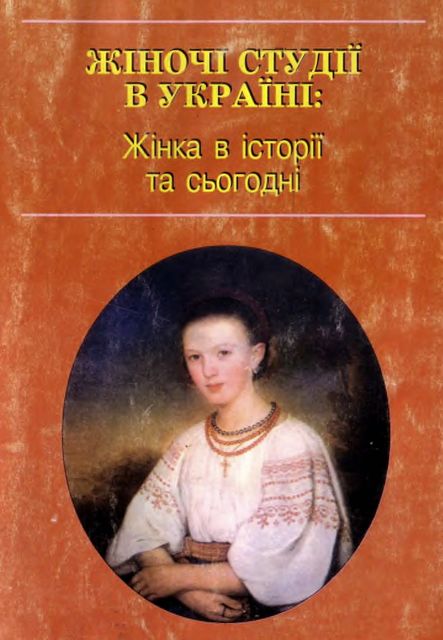

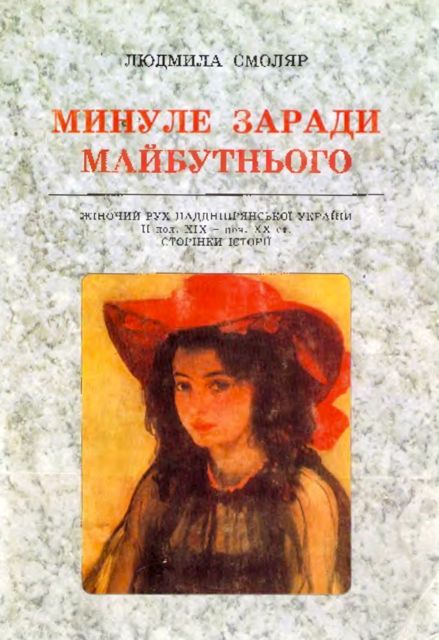

At that same time the first Ukrainian works were published (Lyudmyla Smolyar, Nataliya Lavrinenko, Vira Ageyeva), the first scientific periodical, “Gender Studies Journal”, was founded, and a series of summer schools on gender studies for young scholars were held in Foros (since 1997)[9].

Lyudmyla Smolyar (second from the right) with her fellow scholars of gender studies at the summer school on gender studies organised by the Kharkiv Center for Gender Studies (KCGS) in Foros, Crimea in 1998. Second from the left is Iryna Zherebkina, head of the KCGS.

At the summer school in Foros. Left to right: Kateryna Karpenko, Marian Rubchak, Yevheniia Lutsenko, Lyudmyla Smolyar. Photo courtesy of M. Rubchak.

Self-validation

The next period (2000–2005) was a time of self-validation and consolidation of gender studies. These years witnessed a rapid increase in the qualifications and the number of scholars who thoroughly investigated gender aspects in various fields, defended dissertations in history, sociology, literature, linguistics, political science, and other humanities[10], published monographs, collections of articles and, importantly, textbooks for higher education, and teaching anthologies[11].

Supported by international donors, specialised courses in gender studies were being developed and introduced into an academic programme (first of all in cities where gender studies centres already existed). This attracted more young academics. It was in the early 2000s, that Nataliya Chukhim and Lyudmyla Smolyar made an attempt to create a professional association of gender studies, which demonstrated that this research community had grown in both quality and quantity[12].

Maturity

The year 2006 was a turning point in many ways: the Law of Ukraine “On Ensuring Equal Rights and Opportunities for Women and Men” took effect and “The State Programme on Promoting Gender Equality in Ukrainian Society for the Period until 2010” was adopted.

Discover the history of the Ukrainian law on gender equality in the interview with its initiator, Doctor of Law Tamara Melnyk.

Tamara Melnyk

Gender expertise of Ukrainian legislative branches (2001)

It was these legal acts that included provisions for state support for gender studies. Thus, in the 2010s, gender studies entered a period of maturity and legitimisation, when women scientists were given more opportunities to apply the acquired knowledge and experience in order to develop this field in higher education systematically. In particular, gender studies departments were opened in five Ukrainian universities; a number of gender education centres, which existed with the status of NGOs, were integrated into the structures of universities[13].

Daryna Mizina. Challenges of Gender Education and Gender Studies: between Academia and Activism

Yosh. Educational Projects of “Feminist Workshop” in Lviv

Ivanna Cherchovych. Women’s Education in Ukraine: Historical Overview

The opening of the MA Programme in Gender Studies at the Faculty of Sociology of Kyiv National Taras Shevchenko University in 2017 should be considered a real breakthrough[14]. A number of doctoral dissertations on women's/gender issues (Olena Stiazhkina, Oksana Malanchuk-Rybak, Olena Goroshko, Iryna Zherebkina, Larysa Buryak, Olena Boryak, Olena Strelnyk, etc.) were defended throughout these years which indicates a qualitative shift in gender studies. A growing number of Ukrainian researchers (in particular, young ones) publish their findings in international scientific journals and collections, participate in international academic events, and receive prestigious scholarships for their research internships at leading universities all over the world (Tetiana Zhurzhenko, Tetiana Bureychak, Tamara Martsenyuk, Oksana Kis, Viktoriya Sukovata, Kateryna Kobchenko, Olga Plakhotnik, Kateryna Dysa, Tetiana Dzyadevich, Iryna Koshulap, Alisa Tolstokorova, and others). Another evidence of the scientific maturity of particular research fields is the foundation of professional associations, such as the Ukrainian Association for Research in Women's History, founded in 2010[15].

In the early 2000s, Lviv’s independent journal of cultural studies "Ї" published several issues dedicated to gender issues, which was yet more proof of the growing public and academic interest in gender studies.

Gender Studies. July 2000 Femininity and Masculinity. January 2003 Gender. Eros. Porn. September 2004

Since 2003 the Kharkiv KRONA Gender Centre for Information and Analytics publishes “Ya” (meaning “Myself”), a popular science journal, whose first editor was Tetiana Isaieva.

In the 2010s, journals on gender studies became specialised. In 2015, “The Gender Paradigm of Educational Space” was founded in Kryvyi Rih National University, while “Scientific Notes of Ostroh Academy National University” started a new series called “Gender Studies”.

“The Gender Paradigm of Educational Space"

In 2018, the Feminist Critique: East European Journal of Feminist and Queer Studies was founded. It is a peer-reviewed, open-access academic online journal in three languages, English, Russian and Ukrainian[16].

Issue №1 and 2 of the Feminist Critique Journal

The problems of maturing quickly

The history of the formation of gender studies in Ukraine may seem optimistic, yet, a lot of its aspects are debatable. The studies emerged at a time when science was dominated by a theoretical vacuum and methodological chaos. On the one hand, this allowed them to quickly take roots in particular disciplines (such as literary studies and sociology) in the scientific wasteland caused by Marxism-Leninism. On the other hand, the institutional structures, the intellectual climate and the background inherited from Soviet science happened to be not very fertile ground for critical feminist theory. One of the chronic diseases of science is its tendency to follow the ‘party’s general line’, that is, to adapt to the dominant ideology and political situation. Tetiana Zhurzhenko believes that the alliance of feminism and nationalism in Ukrainian gender studies has resulted in a discourse of ‘national feminism’ with a dominant national component which determines topics and methodological approaches[17]. For example, many researchers of Ukrainian women's history try to answer the question “What is specifically Ukrainian?” rather than “What is specifically women’s?” when studying various aspects of Ukrainian women’s past[18].

The desire to overcome one's own ‘backwardness’ was a serious challenge. To save time and energy, women researchers sometimes neglected the study of classical feminist texts of the 1970s and early 1980s and grasped postmodern theories of gender instead. The attempt to ‘jump over’ several methodological and historical stages created a gap between theoretical research and the down-to-earth demands of the women's movement for informational and didactic resources. Gender studies thus risked losing their social foundation, which might have had devastating consequences.

Another threat is the ‘academic vogue’ partly due to the fact that gender studies are sometimes funded by international donors, which attracts many opportunists. They do not bother to go deep into theory or methodology and simplify gender to the level of essentialism and biological determinism. Therefore gender studies have yet to realise their disruptive potential in Ukrainian science[19].

Translated from Ukrainian by Iryna Malishevska.

[1] In Barbara Einhorn’s apt words, see: Einhorn, Barbara. An Allergy to Feminism: Women’s Movement before and after 1989 // Einhorn, Barbara. Cinderella Goes to Market. Citizenship, Gender and Women’s Movement in East Central Europe. — New York, 1993. — Р. 182–215.

[2] See: Богачевська-Хом’як, Марта. Білим по білому: Жінки в громадському житті України, 1884–1939. — К., 1995; Bohachevsky-Chomiak, Martha. Feminist despite Themselves: Women in Ukrainian Community Life, 1884–1939. — Edmonton, 1988.

[3] See: Грушевська, Катерина. Про дослідження статевих громад в первіснім суспільстві // Первісне громадянство та його пережитки на Україні. — К., 1929. — Вип. 1. — С. 24–33.

[4] For more details see: Кісь, Оксана. Жіноча історія як напрямок історичних досліджень: становлення феміністської методології // Український історичний журнал. — 2012. — № 2. — С. 159–172.

[5] See: Павличко, Соломія. Чи потрібна українському літературознавству феміністична школа? // Слово і час. — 1991. — № 6. — С. 10–15.

[6] Ibid. — С. 15.

[7] All Pavlychko’s scholarly and journalistic texts on the subject are published in a posthumous collection of her works: Павличко, Соломія. Фемінізм. — К., 2002.

[8] For a summary of the work of these centres and the development of gender studies in Ukraine in general refer to: Zhurzhenko, Tatiana. Gender Studies in Ukraine // Aspasia: The International Yearbook of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern European Women’s and Gender History. — 2010. — № 4. — Р. 176–184.

[9] For more information about these projects refer to: The Kharkiv Centre for Gender Studies // www.gender.univer.kharkov.ua

[10] However, the average share of research on women's and gender studies does not exceed 1% of all dissertations submitted for a PhD in social sciences and humanities. This calculation was carried out by the author of the article by analysing dissertation defense announcements published in The Scientific World from 1998 to 2005.

[11] See: Введение в гендерные исследования: Учеб. пособ.. Хрестоматия / Ред. Ирина Жеребкина, Сергей Жеребкин. — Х., 2001; Основи теорії гендеру: Навч. посіб. — К., 2004; Гендерний підхід: історія, культура, суспільство / Ред. Ліліана Гентош, Оксана Кісь. — Львів, 2003.

[12] Due to serious illness and the untimely death of both women leading this process the initiative was inconclusive.

[13] For the first time in Ukraine, gender studies departments opened in five higher education institutions at the same time // The Project “Supporting the implementation of the national gender mechanism” (http://gender.org.ua), September 21, 2010. At the initiative of the Ukrainian National Women's League of America, the private Ukrainian Catholic University launched a Women’s Studies program in September 2012. This lecture series provides students with systematic knowledge and helps develop research on gender studies. For more information see: The UNWLA Lecture Series on Women's Studies // http://lektoriy.ucu.edu.ua/

[14] The MA Programme in Gender Studies // Faculty of Sociology, Kyiv National Taras Shevchenko University (http://www.soc.univ.kiev.ua/)

[15] See: Ukrainian Association for Research in Women’s History // www.womenhistory.org.ua

[16] http://feminist.krytyka.com/ua/issues

[17] See: Zhurzhenko, Tatiana. Feminist (de)Construction of Nationalism in the Post-Soviet Space // Mapping Difference: The Many Faces of Women in Contemporary Ukraine / Ed. M. J. Rubchak. — New York, 2011. — P. 173–191.

[18] See: Kis, Oksana. (Re)Constructing Ukrainian Women’s History: Actors, Agents, Narratives // Gender, Politics and Society in Ukraine / Eds. O. Hankivsky, A. Salnykova. — Toronto, 2012. — P. 152–179.

[19] This problem was thoroughly analysed by Olha Plakhotnik, see: Плахотнік, Ольга. Неймовірні пригоди ґендерної теорії в Україні // Критика. — 2011. — № 9/10. — С. 17–21.